Art & Exhibitions

The Brazilian Embassy in London Reboots a Show of Modern Art That Wowed the City in Wartime

Tarsila do Amaral was among the many artists who donated works but Britain allowed her avant-garde paintings to get away.

Tarsila do Amaral was among the many artists who donated works but Britain allowed her avant-garde paintings to get away.

Javier Pes

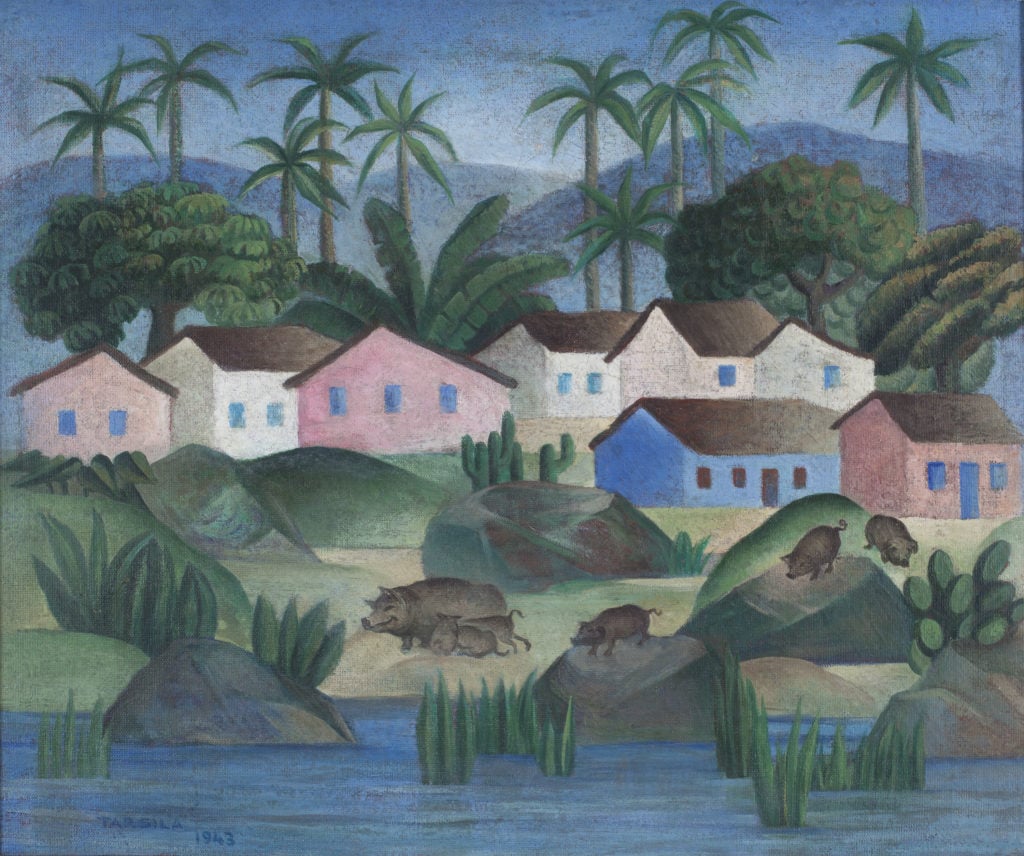

In the darkest days of World War II, leading Brazilian artists brightened the walls of London’s Royal Academy of Arts (RA) and Whitechapel Gallery with a morale-boosting exhibition of modern art. Now, three years of research by Hayle Gadelha, Brazil’s cultural attaché in London, has resulted in an exhibition reuniting 24 of the works for the first time since 1944. Tarsila do Amaral, currently the subject of a solo show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), sent two canvases, one of which has been lent by a private collector in Brazil.

Tarsila do Amaral, Fazenda (1943), private collection.

In total, 70 Brazilian artists donated more than 160 works, which survived the perilous wartime voyage across the Atlantic, to the original show. Proceeds from their sale helped injured members of the Royal Air Force or their widows. Called “The Art of Diplomacy: Brazilian Modernism Painted for War,” the throwback show opens at the Brazilian embassy in London on Friday, April 6 (until May 22).

The Tate could have got a work by a Modernist master for a song. The wealthy British collector and art patron Peter Watson bought a painting by do Amaral for £6 ($8), Gadelha tells artnet News. The Tate acquired its first work of modern Brazilian art thanks to the show. Unfortunately the work is a “stereotypical painting by an obscure artist,” he says. Gadelha has tracked down Cardoso Júnior’s rarely shown painting of a beach scene in the Tate along with other works that are now in public collections across the UK for the show he has co-organized with Adrian Locke of the Royal Academy.

In the 1940s, the RA was an unusual venue for any modern art show. Its president, Alfred Munnings, poured scorn on non-traditional artists, especially if they were foreign. Picasso, whose name he typically misspelled “Piccasso,” was a special target of Munnings’s outrage. Hostility to avant-garde art was suspended as Brazil was now an ally.

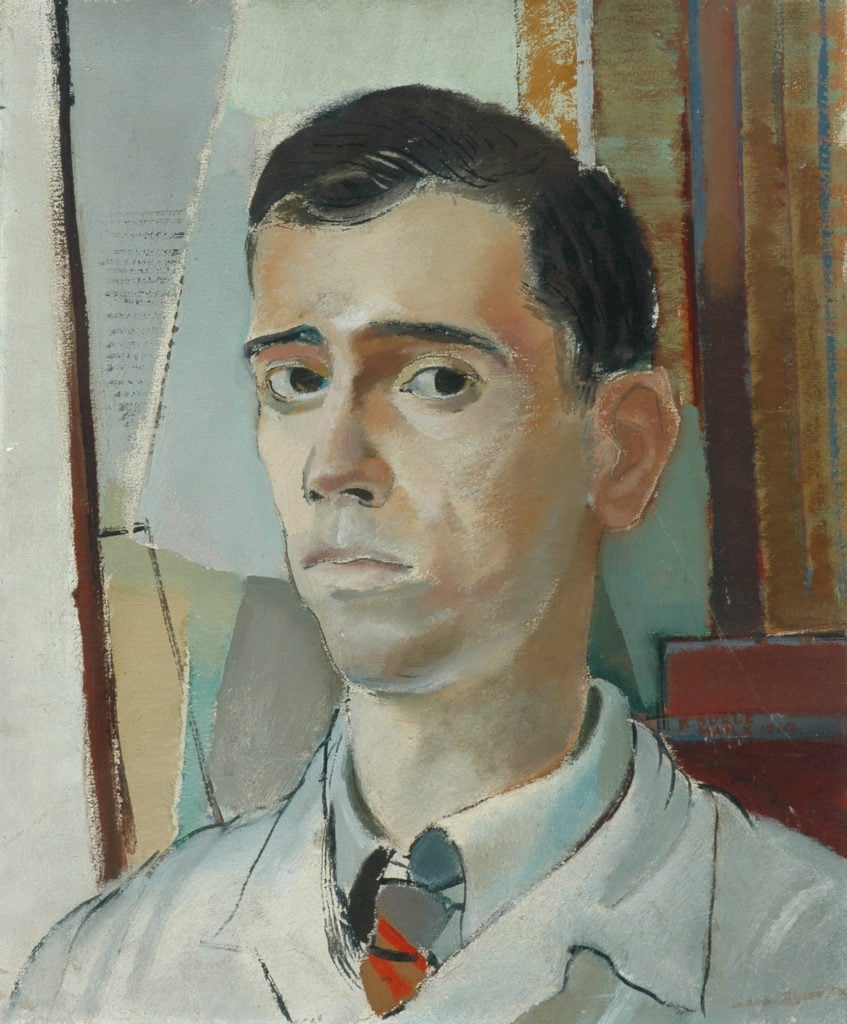

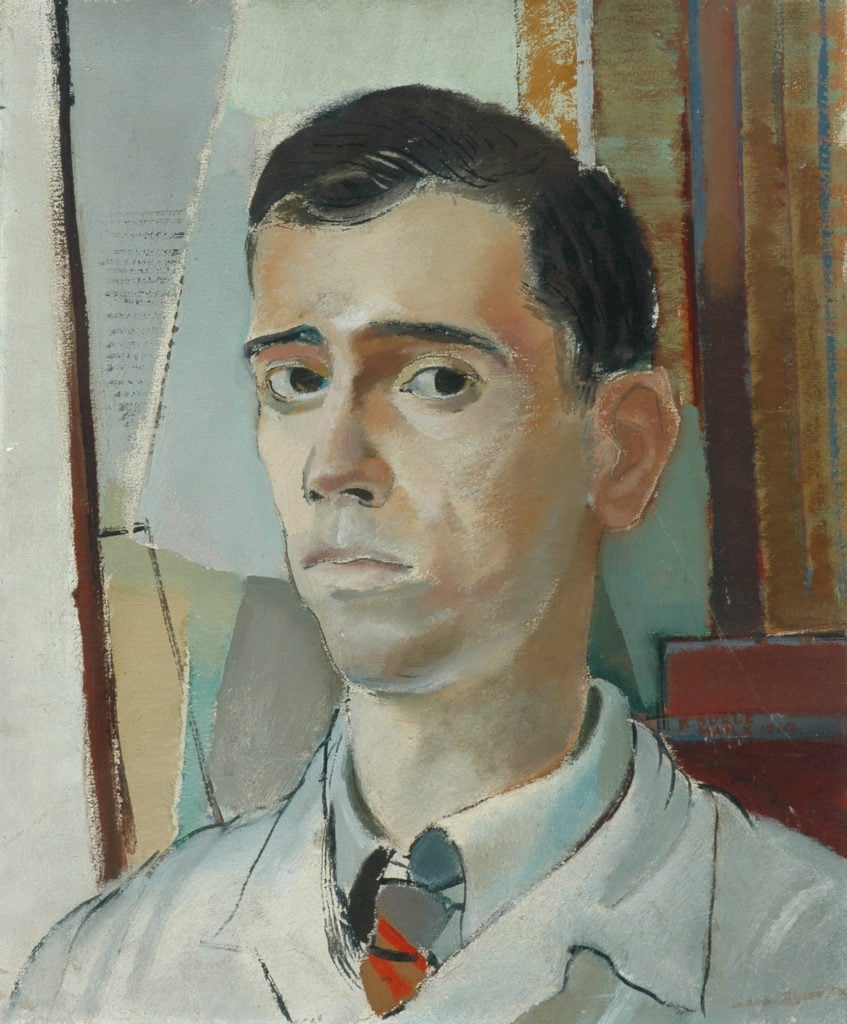

Oscar Meira, Sailor (undated), lent by Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery.

“The British expected naive, colorful art,” Gadelha says. Instead they discovered cutting-edge work by do Amaral, Candido Portinar, and Roberto Burle Marx among others. They were also surprised by an accompanying photographic exhibition of modern Brazilian architecture, including images of some of Oscar Niemeyer’s early works.

The two exhibitions sent to London expressed Brazil’s solidarity with the Allies, after Brazil ended its neutrality in 1942. More than 25,000 soldiers and airmen helped defeat Nazi Germany and its navy fought in the Battle of the Atlantic. There were parallel exhibitions sent to MoMA during the war. After the UK, the art and architecture exhibitions traveled to Paris and helped launch UNESCO in the French capital. “Brazil wanted to play a bigger role on the world stage,” Gadelha says.