Art has long provided a way to explore some of life’s most deeply personal subjects, including sex, intimacy, disease, and death. Over the years, artworks have opened the way for important conversations on such themes, galvanizing viewers and reminding us of all the ways we are connected.

The highly personal experience of breast cancer has been a topic that artists have addressed in profound ways—beginning at a time when the subject was not yet widely discussed. For many years, lack of information and transparency around the disease left women all over the world without proper knowledge of how to combat it. Countless women succumbed to unnecessary death as a result.

Through the efforts of multidisciplinary artists, the experience of breast cancer has been humanized in radical ways, giving us a greater sense of understanding and compassion for those who have suffered from a disease that has claimed too many. In recognition of Breast Cancer Awareness Month this October, here are four powerful artworks that provide glimpses into artists’ experiences with breast cancer.

Hannah Wilke, Portrait of the Artist with her Mother, Selma Butter (1978-81)

Hannah Wilke, Portrait of the Artist with her Mother, Selma Butter (1978-81).

Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Gallery.

Prior to her own diagnosis of lymphoma in 1987, Hannah Wilke paid tribute to her mother’s battle with breast cancer with the bracing work Portrait of the Artist with her Mother, Selma Butter (1978-81).

Known for work that explores feminism and sexuality, Wilke worked across painting, sculpture, photography, video, and performance. She gained early attention for vulva-shaped terracotta sculptures, made in the 1960s. These works, which Wilke would continue to develop throughout her life, were some of the earliest examples of explicit vaginal imagery to enter into the mainstream art world.

Created a little more than a decade before Wilke would lose her own battle with lymphoma, Portrait of the Artist with her Mother, Selma Butter, presents Wilke and her mother bare-chested and side-by-side, as a diptych. Wilke’s mother’s chest has clearly been ravaged by breast cancer—the left side of her body reveals a massive scar in the place where her breast once was.

It is impossible to deny the impact of these contrasting images. Wilke’s mother’s human fragility is fully visible, while Wilke herself appears as the epitome of healthy youth. The artist has adorned her own breasts with found objects to mimic the marks on her mother’s body. She stares directly into the camera, confronting it in a way her mother, in her weakened state, does not.

The juxtaposition of a healthy daughter beside her ailing mother is both harrowing and remarkable. One woman’s suffering is irrefutably visible. The other’s remains below the surface, hidden from public view.

Following her own later lymphoma diagnosis, Wilke would continue to explore the disease in photos, this time through self-portraits taken over the course of her treatment. By confronting death in such a public way, Wilke hoped to remove the stigma surrounding sickness.

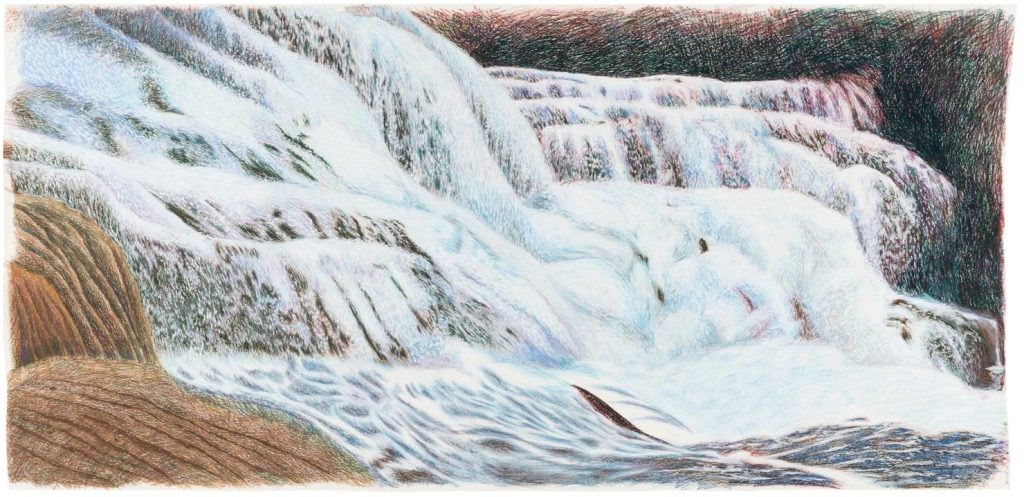

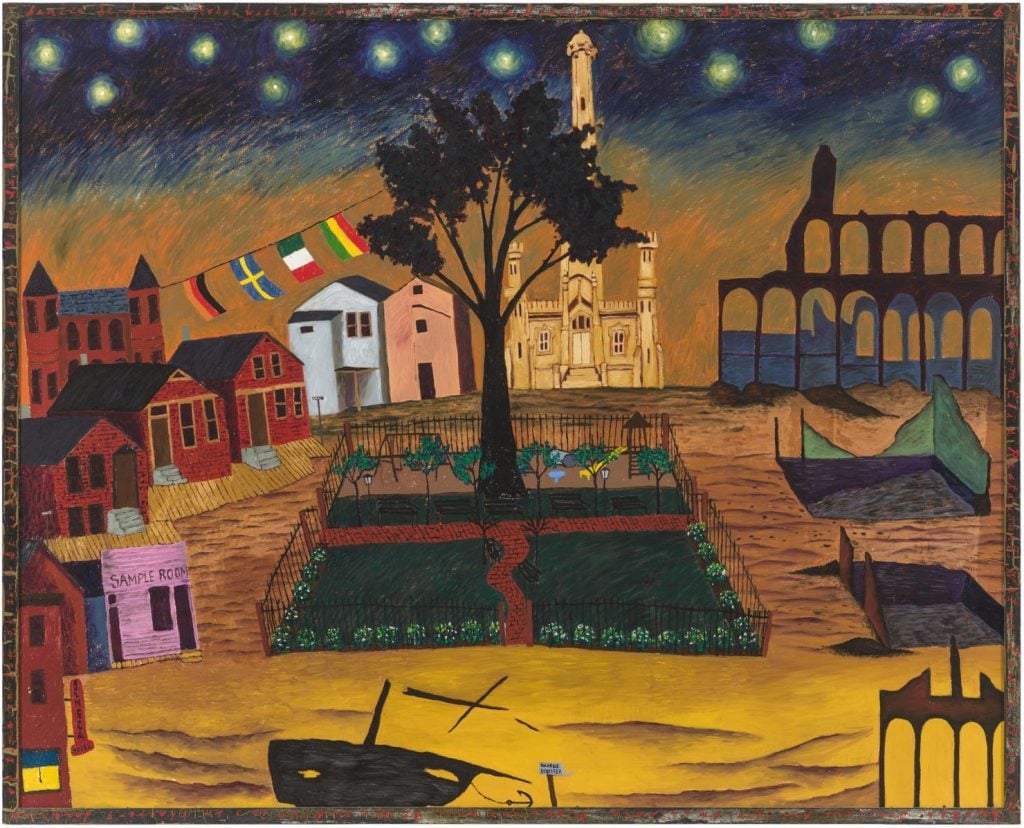

Hollis Sigler, a series of paintings from “Breast Cancer Journal: Walking with the Ghosts of My Grandmothers” (1992-1993)

Hollis Sigler, Some Kind of Love (1992). Photo courtesy MCA Chicago.

For Hollis Sigler, breast cancer was deeply rooted in her family’s history. Both Sigler’s great-grandmother and mother died from the disease prior to her own diagnosis in 1985 at the age of 37. Though the artist underwent a mastectomy and chemotherapy, by 1993, the cancer had spread throughout her body.

Despite these difficulties, Sigler almost immediately began creating artwork that engaged with her illness. In 1992, having already spent years living with breast cancer, she remarked in an interview that she knew she would someday die of the disease, a realization that she said transformed the way she approached her art practice.

It was around this time that she began a series of paintings entitled Breast Cancer Journal: Walking with the Ghosts of My Grandmothers. In total, this body of work includes more than 100 works and acts as a sort of journal in which Sigler recorded personal revelations about herself and her experience of the world.

In the paintings, the artist references her body and the cancer that had consumed it without ever including a figurative representation of either. Instead, Sigler explored the domestic and suburban settings the human form passes through in daily life, infusing familiar spaces with an underlying pulse of alienation and abandonment. Empty furniture and clothing void of its wearer are stand-ins for the artist herself. The resulting images are psychologically charged, and startlingly direct.

The work lives on in a book of related essays of the same name—a work that come to be revered in the decades since Sigler’s death in 2001.

Matuschka, Beauty Out of Damage (1993)

An artist whose work spans photography, writing, and activism, Matuschka transformed her breast cancer diagnosis and resulting mastectomy into an opportunity to spread awareness about the disease. After witnessing her mother fall victim to breast cancer at a young age due to misinformation, Matuschka sought to turn the subject on its head in a lasting way.

Beauty Out of Damage—a self-portrait taken after the artist underwent a mastectomy—graced the cover of The New York Times Magazine on August 13, 1993. It went on to receive a number of accolades, including being selected by LIFE Magazine for their “100 Photographs That Changed the World.”

The image is widely considered the first instance of a “topless” photograph printed by a mainstream publication and carries symbolic weight as the first official public recognition of the breast cancer awareness movement. Its effect in ending the stigma and shame around women’s bodies and sparking a national conversation is still acknowledged today.

Matuschka’s activism played a key role in processing her own personal experience with breast cancer as well. She joined a number of activist groups, using her platform and voice to crusade for women’s health issues, and continues to do so today.

Prune Nourry, The Amazon (2018)

Prune Nourry, The Amazon (2018). Photo courtesy of the artist.

When diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016 at the age of 31, Prune Nourry decided to use her practice to fight back. A multidisciplinary artist, Nourry used several art forms, including film and sculpture, to work through the physical and mental changes that her cancer induced. A seminal work to come out of those explorations is The Amazon (2018), a massive and striking sculpture which the artist created to help reclaim the identity she felt she lost while undergoing her mastectomy.

Modeled after classical sculptures Nourry had seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Amazon represents the wild tribe of women, who, according to mythology, would cut off their breasts to better wield a bow and arrow. This anecdote stuck with Nourry for obvious reasons, and inspired her to build her own Amazonian woman sculpture.

The process of producing the work was cathartic. After a period when Nourry felt she had little choice in her own life, this work was hers to do with as she pleased. Making it allowed her to take back the decision-making power that she felt had vanished during her surgery and treatment.

Once the sculpture was complete, Nourry culminated the artistic journey by covering the work with incense sticks to represent acupuncture needles, a practice which the artist says aided her recovery. In a two-part performance in 2018, Nourry invited friends and family to witness the lighting of the incense sticks and, at the climax, to watch her cut off the sculpture’s breasts. This final, cathartic act symbolized Nourry’s transition from sick person back to sculptor.