What I Buy and Why

British Artist Glenn Brown on His Historical Collection and the ‘Ugly Duckling’ He Bought by Accident

On the eve of Frieze London, we spoke with the artist about his collecting habits, now on display in a new museum.

oil and acrylic over stainless steel. Photo: Tom Jamieson.

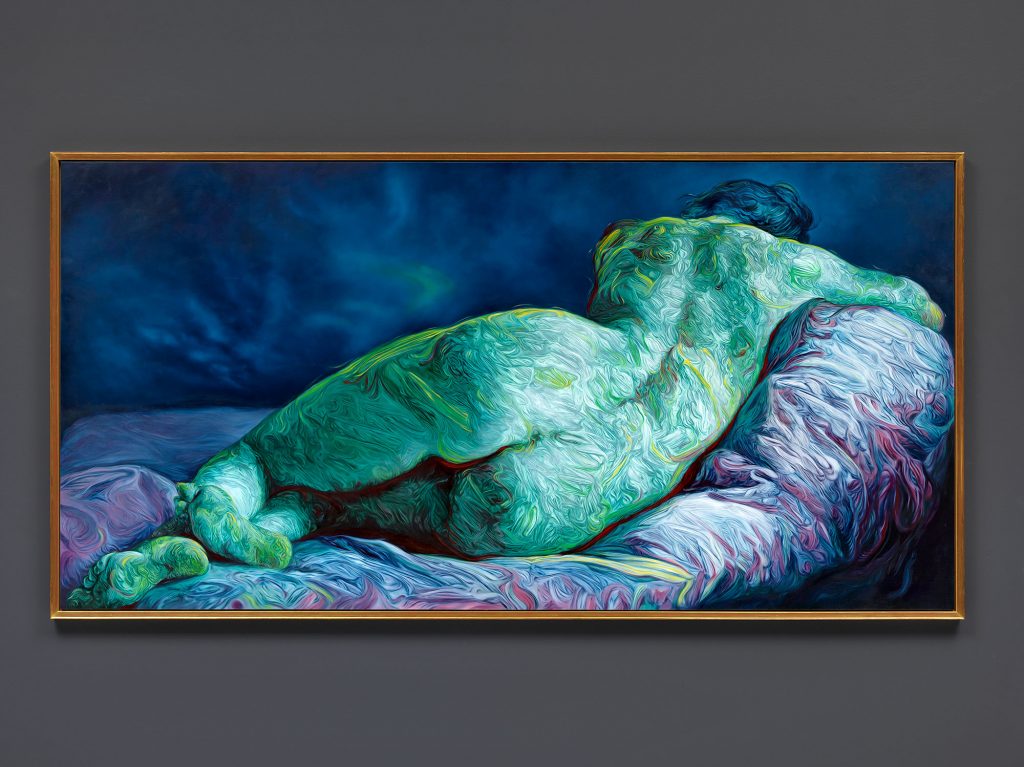

The iconoclastic British artist Glenn Brown pokes at notions of originality by taking historical paintings, drawings, or prints—by the likes of Diego Velázquez, Eugène Delacroix, or Anthony van Dyck—and reimagining them in radical, otherworldly ways that dazzle and discomfit in equal measure. Perhaps he’ll render a nude’s flesh in turbulent swirls of green, or atomize an etched face into a fine mist. In a recent show at the British Museum, his graphic reproductions of Rembrandt portraits, layered on top of each other until they looked like lumps of clay, were paired with the Dutch Master’s works that inspired them.

Never without a natty necktie or pocket square, the would-be academic has turned art history on its head while giving new life to the bygone works of Old Masters. The result is a surreal subversion of art-world classics, a contemporary retelling that has made Brown, a Turner Prize nominee, one of Britain’s most celebrated living artists, with auction prices that soar into the seven digits. The Gagosian-repped artist is exhibited widely, having presented solo shows at the Serpentine Gallery in London, Tate Liverpool, and the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle.

Installation view of the Brown Collection in Marylebone. Courtesy of the Brown Collection.

While he doesn’t think of himself as a collector per se, he’s nonetheless built a sizable archive containing both his creations and that of other artists. To house the Brown Collection, he recently opened a museum in London (open to the public and free of charge), a renovated 1905 mews warehouse in Marylebone with four floors of exhibition space. The current exhibition, “The Leisure Centre,” furthers his exploration of originality, asking the viewer to become a flaneur, “questioning which century a work was made, who made it, and why.”

On the eve of Frieze London, we spoke with Brown about some of the historical works in his archive that have inspired him the most.

What was your first purchase?

I do not consider myself a collector. I buy works when I feel I can beg, borrow, or steal something from them. They become very important tools for me to learn how to be a better artist.

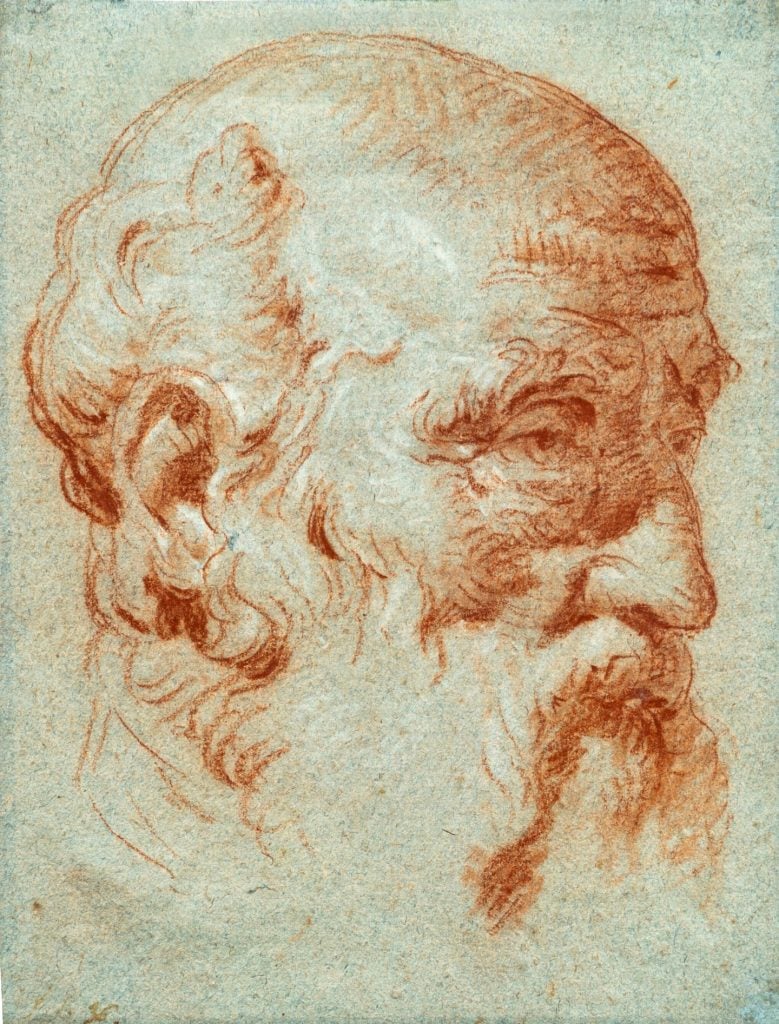

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Study of the Head of Giulio Contarini. Courtesy of the Brown Collection.

What was your most recent purchase?

I just purchased a beautiful 18th-century portrait drawing by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. It’s red and white chalk on blue paper, which is very typical of Venetian Baroque drawing. I already have a drawing underway that uses elements of it. I have used Tiepolo’s color, line, and figures in many paintings and drawings over the past few years.

Tell us about a favorite work in your collection.

I find the idea of picking a favorite rather childish. As a human being, you can enjoy the difference and individuality of people and art. One minute I can be loving a Gillian Wearing sculpture, then by the afternoon I can be bowled over by a Jan Van Noordt portrait. I only buy things if they are my favorite at that moment.

Which works or artists are you hoping to add to your collection this year?

I am not sure I am that strategic. As I collect such a broad spectrum of artists throughout the centuries, trying to collect with a strategy is problematic. In a sense, it doesn’t matter if the artist is famous or relatively unknown, whether it’s an artist I already have in the collection or haven’t even encountered before. What is important is whether the work inspires me.

Hendrick Goltzius, Pieta etching. Courtesy of the Brown Collection.

What is the most valuable work of art that you own?

The most valuable to me are the ones that have influenced me the most. I have in my studio a small etching, Pieta from 1596 by Hendrick Goltzius. I can’t understand how the human hand and brain can make an artwork so emotionally engaging and technically brilliant.

Where do you buy art most frequently?

Auction houses and art dealers. What I have learned is to see the pieces in the flesh first. It’s really tempting to be seduced by an image online, but it doesn’t tell you if the work has that sense of magic or the vivacity that turns a work of art into something you fall in love with.

Installation view of the Brown Collection in Marylebone. Courtesy of the Brown Collection.

Is there a work you regret purchasing?

Be wary of auction houses. I wrote down the lot number next to the painting I wanted and left a bid. When I received the invoice I realized I had bought the painting next to it, a very dark, late 17th-century Neapolitan School painting of Saint Elias. I lost my bid for a really beautiful painting and gained an ugly duckling.

What is the most impractical work of art you own?

I did a show in 2017 at the Stefano Bardini Museum in Florence where I made work to fit some of their esteemed collection of Renaissance frames. I was so enamored by the process of the frame being a starting point for a new work that I began to collect antique frames from all over Italy—Florence, Bologna, Venice, and Rome. I have a huge and very ornate 17th-century carved gilt wood Florentine frame made for the Medici family. We haven’t dared get it out of the crate to hang it as it’s so fragile.

Glenn Brown, On the Way to the Leisure Centre (2017). Photo: Mike Bruce. Courtesy of the Brown Collection.

What work do you have hanging above your sofa? What about in your bathroom?

I painted On the Way to the Leisure Centre (2017), a large, reclining, green nude, specifically to hang above an imaginary sofa. I loved the painting so much I couldn’t sell it, but have never actually hung it above a real sofa. In our bathroom, we have an 18th-century portrait by Ubaldo Gandolfi. It is a wonderful and sensitive painting, in a room that happens to be a bathroom.

Ubaldo Gandolfi, Portrait of a Young Man Half-Length Wearing Senators Robes. Courtesy of the Brown Collection.

If you could steal one work of art without getting caught, what would it be?

Why would I want to steal a painting from a museum? I love that museums have art and objects on public display. If being a collector means denying access to objects and their ability to be shown, why would I want to be a collector?

What work do you wish you had bought when you had the chance?

There was a portrait painting by Bernardo Strozzi (1581 Genoa—1644 Venice) I had the chance to buy. It was not in very good condition and had been partially overpainted, but even I could tell it was a magnificent work. I have since made a drawing and a painting after it, so obviously I regret not buying it. I have now seen it restored and it really is a masterpiece.