A new film installation, Viva Voce (2024), by Keith Piper has been unveiled at Tate Britain. The artist, a founding member of Britain’s BLK Art Group, is the first to be commissioned as part of the Tate’s new contemporary art program that will respond to a highly controversial mural that once decorated the main restaurant in the museum. It’s one of many recent endeavors by British art institutions to recontextualize problematic colonial pasts.

The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meat was painted in 1927 by Rex Whistler when he was still in his early 20s. A hunting party is shown traveling across the imagined land of Epicurania in search of exotic foods. In one particularly offensive scene, they encounter and then attempt to enslave a young Black boy while his mother watches from the high branches of a tree.

Rex Whistler’s mural The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meat (1927) was painted to decorate the main restaurant at Tate Britain in London. Photo: Jeffrey Greenberg/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Though its racist caricatures of Black and Chinese people and depictions of slavery have long been questioned, the mural came under increased scrutiny in 2020 after the editorial platform The White Pube called attention to the imagery. This prompted a series of internal discussions as well as the consideration of perspectives from outside the institution. Eventually, Tate decided not to remove the mural. Instead, it would house “a new display of interpretative material, which will critically engage with the mural’s history and content, including its racist imagery.”

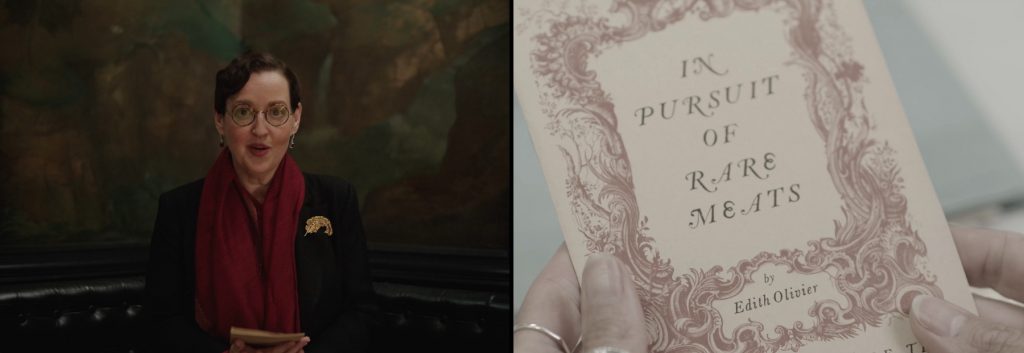

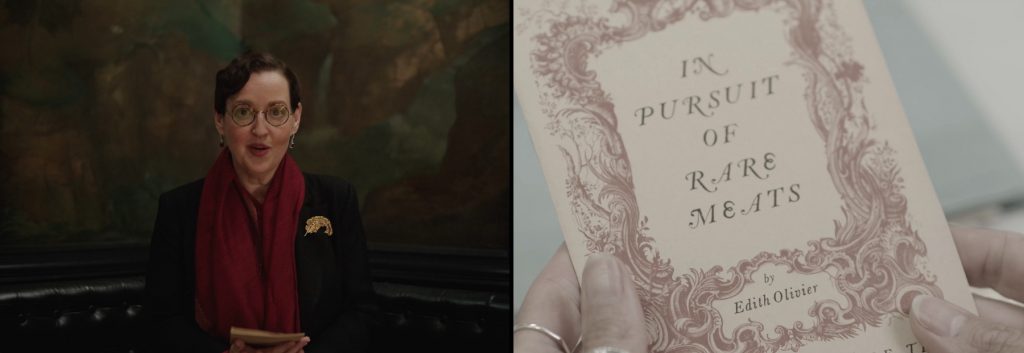

Piper’s inaugural commission, Viva Voce, is a projection across two screens suspended in the middle of the room. The work imagines a meeting between the artist and a fictional modern day academic, Professor Shepherd, who challenges Rex Whistler, asking some of the questions we might wish we could go back in time and get answers for.

“It’s so important that a museum is a space where a historical object can sit,” Piper said, speaking on Tate’s podcast “The Art of Change.” “Maybe the original intention of the people that made that object is hugely reprehensible to us,” but, he added, the museum’s role is to “help us have an understanding of what that moment was. It becomes really important to look in depth at the history of these objects. That’s not to endorse them.”

Keith Piper, Viva Voce (2024), film still installation view. Photo: Joe Humphrys, © Tate.

The installation’s concept was inspired by Piper’s own experiences as a teacher working with young people. It allows him to imagine what Rex Whistler’s intentions might have been and delve into the social and political context of the 1920s. For this reason, it also features some archival footage from the period.

“It could have just been that, as a very young man, he found that funny,” Piper suggested. “Humor is a very powerful thing, and obviously now in retrospect we’d look at that and say, ‘unpack that please.’ I think its so important to read an artist’s work in the context of the time.”

Another character in the film is the artist’s friend Edith Olivier, an older woman who wrote the entire narrative for the mural, which was never finished, in a pamphlet. Piper has described the document as a “map” that can be used to “decode” the mural’s imagery. For example, it reveals that an otherwise ambiguous figure in the tree is meant to be the kidnapped boy’s mother.

Keith Piper, Viva Voce (2024), film still. Photo: © Keith Piper.

Piper also pointed out, that racist imagery was certainly not inevitable at the time that the mural was painted. He compared the work to two others in Tate’s collection that were also completed in 1927. In The Resurrection, Cookham by Stanley Spencer, Piper noted, the artist included Black figures “but he’s actually attempted to make them quite detailed and nuanced. They are not caricatures.” Another example is Jacob Epstein’s Paul Robeson (1898-1976), currently on short term loan to Tate Britain from York Art Gallery.

He added that, shortly before Rex Whistler died in 1944 while fighting in World War II, he painted “a really fantastic painting” of a mixed-race child. “I think the images [in the mural] are deeply racist,” Piper added. “I hope I haven’t pulled any punches with that. It is even more racist, in a sense, than most people have realized.”

Keith Piper, Viva Voce (2024), film still installation view. Photo: Joe Humphrys, © Tate.

“The Tate has a duty of care to artworks within its collection,” said Nikki Frater, an art historian and expert on Rex Whistler. “It would be a horrible thought to have this room darkened and hidden away when its actually a really good opportunity to look at this young artist trying to work out what might have been going on in his head.”

This idea that problematic historical collections should not be hidden away but instead recontextualized with the help of contemporary artists has been a popular strategy among U.K. museums in recent years. Currently, Kerry James Marshall, El Anatsui, and Frank Bowling, are among many artists featured in Entangled Pasts at the Royal Academy in London. The British Museum also recently announced a collaboration with Hew Locke that will see the artist select items with colonial past for re-examination.

“I want to bring people beautiful objects with awkward histories, and smaller objects easy to walk by, that are just as compelling when you stop and look,” he said. “There is a fascinating story hidden in plain sight, here and in many other museums across the country.”

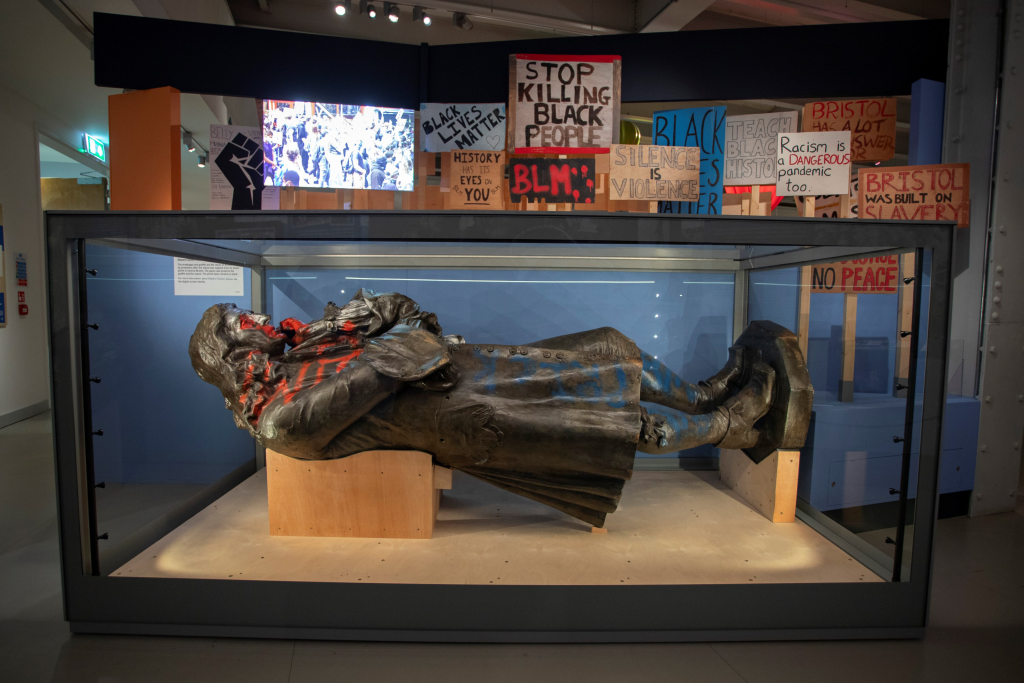

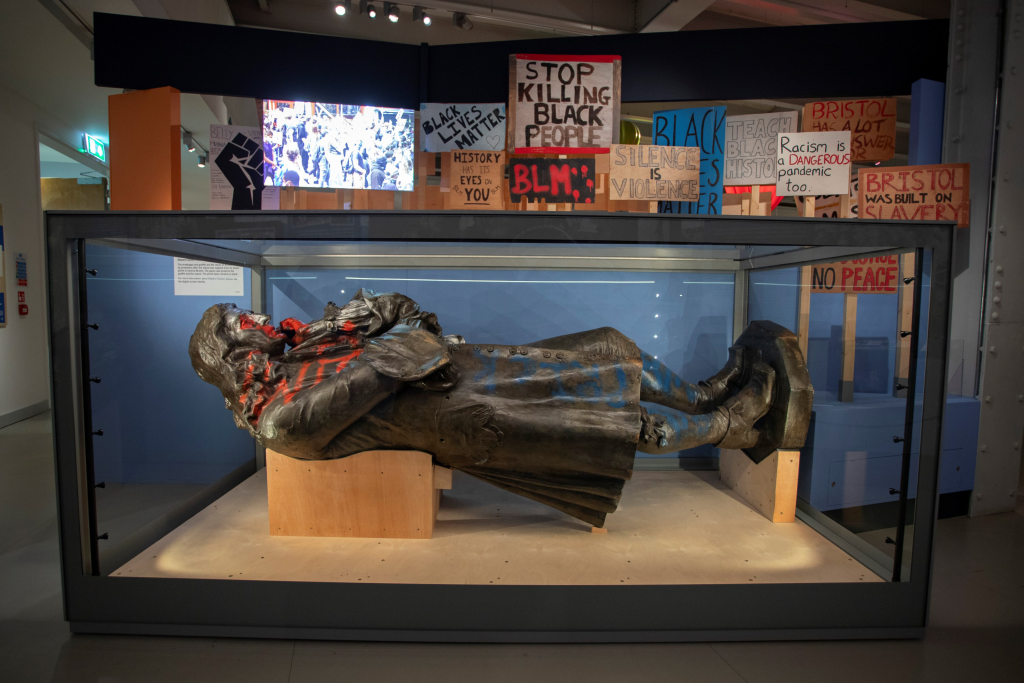

Installation view of a statue of slave trader Edward Colston at M Shed Museum in Bristol. Courtesy of M Shed.

Last week, a statue of the slave trader Edward Colston was installed in Bristol’s M Shed museum after it was torn down from its original public plinth in 2020 by Black Lives Matter (BLM) protestors who had taken to the streets to express anger over the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis. What to do with the toppled monument became a subject of public debate but it was decided that it should be treated as a historical artifact and entrusted to a museum.

Striking a compromise between those that wished for the sculpture to be destroyed and those that believed it should be preserved as a document of the past, the museum’s display of the sculpture is deliberately designed so visitors must actively choose whether to encounter the work or to avoid it. Positioned horizontally, rather than upright, Colston appears within a contextualizing exhibit that features replica BLM posters and an interpretation board.

“We held ourselves together and we have got to a point where we now have this incredible display, with the statue in context, with the story preserved,” said Bristol’s mayor Marvin Rees, Europe’s first Black mayor, at a launch event. “Making space for people to think about Bristol’s history and its relationship with people of black African heritage.”

Keith Piper’s Viva Voce (2024) at Tate Britain is ongoing. The museum has not yet announced which artist will be chosen for the second commission in response to Rex Whistler’s mural.