Politics

Bruno Latour, the Philosopher of Science Who Changed Art Theory, Explains His New Book on Climate Change

The author of 'Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime' on the Yellow Vest movement and his manifesto for the EU.

The author of 'Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime' on the Yellow Vest movement and his manifesto for the EU.

Ben Davis

It’s hard to overstate the influence of Bruno Latour. Stretching well beyond his native discipline of “science and technology studies” (which he helped create), it by now permeates the humanities.

This spell fully extends to art. Books and essays such as We Have Never Been Modern and “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam?” are staples of both classroom and studio, credited (or blamed) with setting the stage for the recent curatorial turn towards “object-oriented” philosophy, as well as what has been called the “post-critical” turn in art theory.

The French thinker’s latest book, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (Polity, 2018), focuses especially on climate change as the new problem around which politics are—and should be—organized. Because Latour’s scholarship has questioned the rhetoric of scientific objectivity, much of the coverage of the book has read it as his defense of his theories from association with the present-day “post-truth” politics that feed climate-change denial.

Down to Earth is that—but it also is a lot more, much of which will be highly controversial. In a short, dense tome, Latour challenges the rhetoric of both Marxist and Green activism; argues that we should abandon the distinctions between Left and Right in politics; proposes a new project to map the “dependencies” of all creatures on the earth; and concludes with a seven-page manifesto defending the European Union as a model of collective identity.

In December, with “Yellow Vest” protesters shutting down sections of Paris to demonstrate against a carbon tax, I sent Latour a set of questions about his new book by email. Here are his answers.

Bruno Latour. Photo by KOKUYO. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

With the Yellow Vest protests gripping France, it seems to be an important time to talk about your new book. How does Down to Earth contribute to our understanding of this unfolding crisis?

Really, it is as if I had generated the crisis just to prove my point! Protests from people in suburbia are, for the first time, connecting questions of social justice with questions of ecology around the taxation of gas—a key question in America, but also in France, at least in suburban regions because of the decrease in public transportation. But of course, the State, which is still thinking according to the old climate regime, is unable to listen to this complaint and is just reacting in the old ways, puzzled and repressive.

For me, the Yellow Vest movement is a small example of the big example given by Brexit. It took two years for the whole country to shift from a complaint about identity—“let’s get out”—to a realization of their ties to Europe—economy, law, worker’s protections, etc. So if my claim was that the question of energy, territory, soil, identity, and material ecology are now the central drive of political positioning—well, here you are.

Protesters march on Rue Sainte-Catherine in Bordeaux, southwestern France, as they take part in an anti-government demonstration called by the “yellow vests” (gilets jaunes) movement on January 26, 2019. Photo courtesy Mehdi Fedouach/AFP/Getty Images.

You write that “the issue of climate-change denial organizes all politics at the present time” and suggest that neoliberal economic policies suppress the reality of a shared environmental fate, writing: “the obscurantist elites… understood that, if they wanted to survive in comfort, they had to stop pretending, even in their dreams, to share the earth with the rest of the world.” You acknowledge that this can sound like “a conspiracy theory,” and it does seem to emphasize that the climate crisis is the result of a master plan, as opposed to the result of an irrational market. So why frame the problem this way?

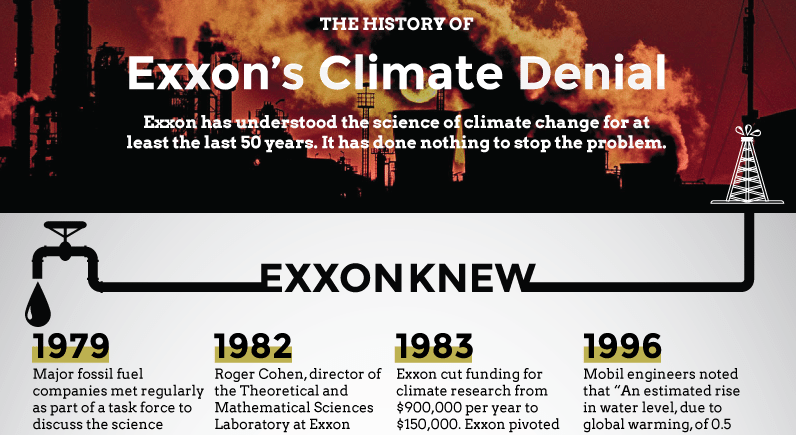

I agree that when I wrote the book it was more of a hunch. But two years later, from [Nathaniel] Rich’s very interesting inquiry in the New York Times [“Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change“] to [Thomas] Piketty’s new book on CO2 inequalities, to [Naomi] Oreskes and [Dominique] Pestre’s work, I would now claim that the denial of the bad news coming from scientists and the urge to deregulate after the end of Keynesian policies come at least at the same time. The precise study by Pestre about the OECD reaction to the Club of Rome is a case in point as well [“Knowledge and Rational Action: The Economization of Environment, and After“]. So is the case I cite of Exxon—although slightly later.

Deregulation is certainly not market irrationality, as you say. It’s a clear and well documented collective decision. Now, is climate denial an adjuvant or, as I claim, the surreptitious and main drive? I don’t know. But I would make the claim nonetheless, to be tested—and anyway now with Trumpism, it’s clear.

Graphic timeline of Exxon’s role in climate change denial. Image courtesy Greenpeace.

You argue that we need to stop thinking of nature as something separate and static and embrace what you call “the Terrestrial,” defined as an understanding of humanity’s interdependence with other agents. But does this transform a political problem into an intellectual one? It seems that everyone from Exxon to the US Defense Department is very aware that ecological collapse has devastating effects on humans. So the problem is not a lack of knowledge, but that the present system of competition between corporations and nations compels them to act with short-term interests instead of long-term human ones. Why develop a new intellectual paradigm, rather than a new system of material incentives?

Ah, ah—here you are going to say that I am too French, and that I tend to see ideas where there are interests, but I’d like you to remember that “acting in short-term interests” over, as you say, “long-term human survival,” does not come naturally to humans… it has to be produced, imposed, taught, by a vast apparatus in which you have to consider the science of economics, as well as marketing, and the complete set of ideas—sorry, they are ideas—associated with the notions of nature as a mere resource.

The range of studies of historians of economics on the invention of liberalism is impressive, from Marshall Sahlins to Timothy Mitchell, to take just two examples. So we, the critics of the old climatic regime, have to address all the issues. You are right that this includes the history of material economic interests, but it also includes the ideas that have generated this narrow notion of short-term material interests in the first place.

When one of your ministers says, “the US is rich in material resources and we are not going to leave them in the ground,” it is an idea, and a powerful and nefarious one, that “compels” short-term destruction….

Trump advisor Preston Wells Griffith at COP 24, the 24th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Katowice, Poland on December 10, 2018, where he announced a US policy of continuing to exploit its natural resources. Photo by Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

Much of your work is against the objective, god’s-eye view of science, which you say is a toxic abstraction that divorces humanity from its ecological dependencies. Yet the most programmatic part of your book declares that we should develop a “ledger of complaints,” similar to those drawn up during the French Revolution, when every local community was asked to list its political grievances. You say it’s urgent to create a total register of “the properties of [the] terrestrial—in all the senses of the word property—by which it is possessed and on which it depends, to the extent that if it were deprived of them, it would disappear.” How is this total ledger of dependencies different than the absolute, god’s-eye vision of science?

You would be right if the writing of the ledgers was made by experts studying what the average citizen has to say and then compiling them. But this is the wrong paradigm, the one imposed by, as you say, a god’s-eye view. Well, it is complicated because God has lots of other views, but let’s forget that.

The 60,000 ledgers produced in a few months by the French people had the effect of creating the French as a people, since it had never been done before at such a level of detail and with such a connection between description of the lived territory and protestation against the unfairness of taxation. I have done many of those exercises, and funnily enough, as I said earlier, the government is now involved in a “national debate” that, unfortunately, is a travesty of the 1789 episode, which is understandable because President Macron would be ill at ease with the parallel.

In the exercise I made, it is fascinating to see the distance between mere protestations—usually a rehash of what people have heard on social networks—and the written ledger of complaints. Again, the best example is Brexit, where you see the extreme pain with which people move from protestations to a realization of what they depend on to survive for good. [It has taken] two years to realize they were benefiting largely from what they hated so much.

Cover of Bruno Latour’s Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (Polity, 2018).

The book ends with a manifesto for Europeans, asking them to embrace the European Union as a positive example of post-national identity that can be a model for responding to the ecological crisis, since the environment can’t be addressed within any national frame. You write of the EU: “It is by the intricacy of its regulations, which are attaining the complexity of an ecosystem, that it shows the way. Exactly the sort of experience that one needs to approach the ecological mutation that is straddling all borders.”

This emphasis seems to be a reaction to the anti-globalism of Trump and Brexit. Yet EU regulations have, among other things, been criticized as tools of the more powerful states, and are blamed for the massive contraction of the Greek economy, which has also led to rising fuel taxes, even causing a rise in pollution as some Greeks revert to burning wood for heat. What about the EU seems to be a positive alternative model of identity? And is it the actually existing EU, or a theoretical “Terrestrial” EU?

You are perfectly right. But my attempt is to shift attention from Europe as an institution—with all its defects and qualities—to Europe as a place, a soil, a Heimat, the Germans would say, with all the dangers that link soil and people, but also with the reality that the idea of a European motherland implies for people when you discuss it with them for five minutes. And the reason is, of course, that this is the time to distinguish the EU as a very useful and dysfunctional machine—but so is the American State—and Europe as a civilization.

At the time of the conservative revolution, when every nation state falls back behind its walls and even its ethnic fatherland, it is absolutely crucial for political scientists to re-ground, and also to enlarge what it means to belong to a place—especially when it is the earth that is in question. So it is nothing “theoretical,” but it is something, I agree, which, strangely enough, is rarely articulated publicly.