People

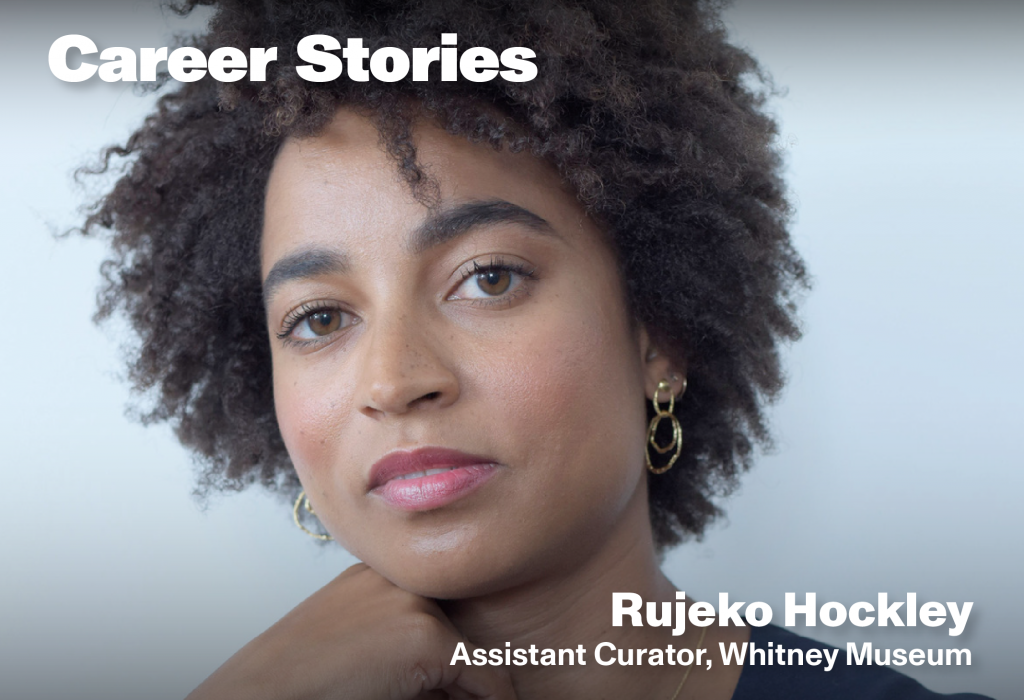

Curator Rujeko Hockley on the Lessons She Brought From Her Early Job at the Studio Museum to Her New Role at the Whitney

How the esteemed Whitney curator got her start.

How the esteemed Whitney curator got her start.

Katie Rothstein &

Samantha Baldwin

Curator Rujeko Hockley has always woven art history into the fabric of her life’s pursuits. She described a turning point that came during while an undergraduate at Columbia University, when she realized that art history did not have to be such a narrow course of study.

“Topics I was interested in around questions of equity, questions of race, questions of history, questions of class—all of these questions could be a legitimate and valid way to think about the history of art,” she said.

After graduation, she stepped into the museum world as a curatorial assistant at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Since then, she’s taken on roles at the Brooklyn Museum, co-curated a Whitney Biennial, and now works as an assistant curator at the Whitney Museum.

Read on to hear more about her path to curating, the latest exhibition she organized, and the advice she would give her younger self.

The reality of working in a museum can be very different from studying art history in a classroom, and you jumped in right after college. What was that transition like?

I mean, I think it was a lot more like a job. [Laughs] I think the difference between studying art history and working as a curator—whether you’re in an institution or you’re independent, or what kind of institution you’re in—is the logistics side. A big part of our job is logistics, coordination, working with different people and different groups of people to make a project happen. And so one of the things I really liked about it is that you both have this kind of intellectual challenge and this historical challenge, to think through these questions of art history. But at the same time you had these creative solutions, you know, to issues around installation, troubleshooting, working with the different departments, working with artists. So I think that is the part that art history doesn’t have, it’s very distinct, and they obviously inform one another, but they aren’t the same at all.

What was one lesson you learned from your experience at the Studio Museum that you carry with you to this day?

There are a lot of things that I learned there that I definitely hold very dearly, but I think one of the most important things that I really do reflect on and come back to is artists, and the importance of artists, and the centrality of artists to the work that we do. It’s not an accident that that institution is called the Studio Museum, and named after the artist-in-residence program, and the studios that are literally in the building. And part of working there is working with the artist in residence who’s here, working on their show, working on their catalogue. Watching them develop a body of work over the course of the year, they become a part of the fabric of the museum in a really unique way. Something I learned at the Studio Museum was to really prioritize artists to make sure they are at the center of whatever you’re doing, to really recognize that what we are doing is in service of them—in service of their highest dreams of realizing their work at the level and in the way in which they envision it.

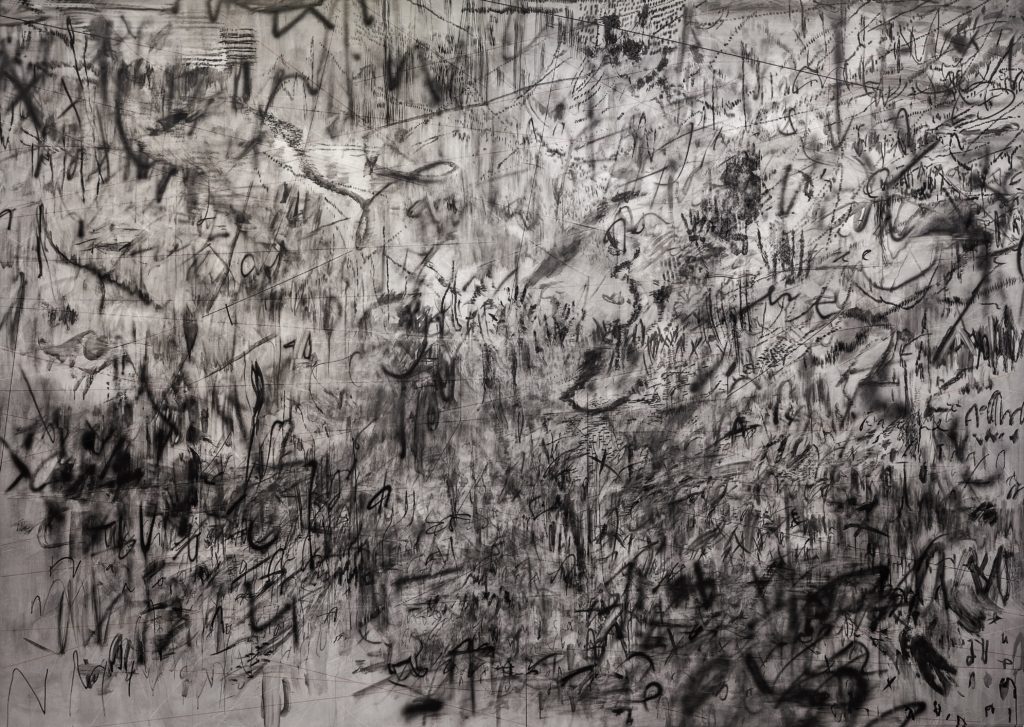

Julie Mehretu, Invisible Sun (algorithm 4, first letter form) (2014). ©Julie Mehretu, photo by Carolina Merlano.

I also read that one of your first roles after you were hired at the Whitney was to help curate “An Incomplete History of Protest.” That’s an intense project to be thrust into right off the bat, so I’d love to know a little bit about what that was like?

That was a really great project to be thrust into, because it was a way to start to learn the collection, which is always a really valuable thing to do with the beginning of a new job at a collecting institution. It also allowed me to work with my colleagues; I co-curated that show with Jennie Goldstein and David Breslin. Both of them had come to the museum not that long before me. They’d been kind of working on this idea, but it was in an inchoate form, it was very early, they just had a huge checklist. And so it was great to be able to be involved, and in a quite short time—I started working at the Whitney in March 2017 and that show opened over the summer. It wasn’t a huge amount of time. And so we kind of had to work quickly, and it was very gratifying to see something come together in a collaborative way.

I think that is very much my wheelhouse, I guess, as a curator, as a scholar, it was the intersection of art and politics, or art and activism, or art and protest, whatever you want to call it. I had just completed a show, or was in the midst of completing a show, at the Brooklyn Museum called “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85,” which looked at the intersections between second-wave feminism and its treatment and assumption and non-assumption of representativeness by women of color, especially Black women, and then its relationship to Black women artists specifically. So I was already very steeped in thinking in this way, about these intersections, and thinking about these things, even going back to my work at the Studio Museum, my work as an undergrad, you know, these are things that I had really been thinking about and really invested in for a long time, so it felt very natural that that was what I would be asked to work on. I was really excited.

Tell me about your process for your latest show, a mid-career retrospective of work by artist Julie Mehretu, from the inception of it to the final day of hanging in the galleries?

This is a co-organization between the Whitney and the L.A. County Museum of Art, and my co-curator is Christine Y. Kim, who is a curator at LACMA, and Christine and Julie have known each since Julie was an artist in residence at the Studio Museum; Christine started working there around the same time. So they have been collaborators and friends for many, many years, more than two decades. And they started thinking about this show actually in 2013. They have a long path on this show. And then when I came to the Whitney, in addition to working on “An Incomplete History of Protest,” I also was asked to look through the traveling show packets that we had been sent, and I would think about whether any of them felt portent. Julie’s books really stood out to me as being something that could be really incredible at the Whitney. And then over the course of conversations, it became more of a co-organization project where the Whitney would take on the catalogue, and LACMA would take on the loans, but Christine, Julie, and I would really work on the exhibition together, which is what happened.

I would say it’s been a long road for us, of course the pandemic has extended it almost a year, as far as when we were supposed to open versus when we opened. It doesn’t feel like it’s been as long as it has, which is I guess a testament to what a lovely group of people it is.

Julie Mehretu, Haka (and Riot) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, © Julie Mehretu, photo by Tom Powel Imaging.

In terms of your practice as a curator, are there any processes or rituals that you employ in every show you curate?

Research is the main one. [Laughs] Research, and a really deep dive into what’s been written about somebody, the work that they have made, and just really try to get to know their practice as well as you can. And that’s in the sense of a solo show. If it’s a group exhibition, then I think it’s a different kind of research. If it’s a systematic exhibition, for example, like the Biennial, which I co-curated with Jane Panetta, we did a lot of research initially into past biennials at the Whitney, thought a lot about the idea of the biennial in general, as it’s been realized internationally over the last 20 plus years.

Of course, once we got into the phase of thinking about artists, then we did research on individual artists, but it’s a different process with kind of a thematic group shown versus a monographic show.

What is one piece of advice you would give your younger self at the start of your career?

I would encourage myself to have faith. I think that means both in the work and also in yourself, in your capacity and ability. Even through those times when you’re in your early to mid-20s and feel kind of like, “What am I doing with my life? And is this what I want to do, and is this right, and should I do something else?” And those feelings are not, let’s be serious, isolated to your early 20s. They can happen any time, and they cycle.

What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given?

A friend of mine, Christopher Myers—this was advice that his father [Walter Dean Myers] actually gave to another friend of ours, which Christopher shared at [Walter’s] funeral. And the advice was: “Don’t act like you don’t know what you know.” And I think it’s connected to this idea of having faith, and believing in yourself. Especially when you’re younger, there can be a tendency—and this can strike at any time, depending on the context, and who you’re talking to, and if you feel like you’re the person that needs an authority in the room, or you’re the person that’s supposed to be quiet and listening—don’t act like you don’t know what you know. Don’t sell yourself short, or challenge yourself when you’re being asked to speak on things that you know about. That’s why you’re there. That’s why you’re in the room.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.