Art History

Cecilia Vicuña Had to Repaint One of Her Works in the Venice Biennale Because a Friend Lost It When Moving Into a New House

The artist revealed the untold story of a previously discarded work during a chance encounter with its new owner.

The artist revealed the untold story of a previously discarded work during a chance encounter with its new owner.

Maya Asha McDonald

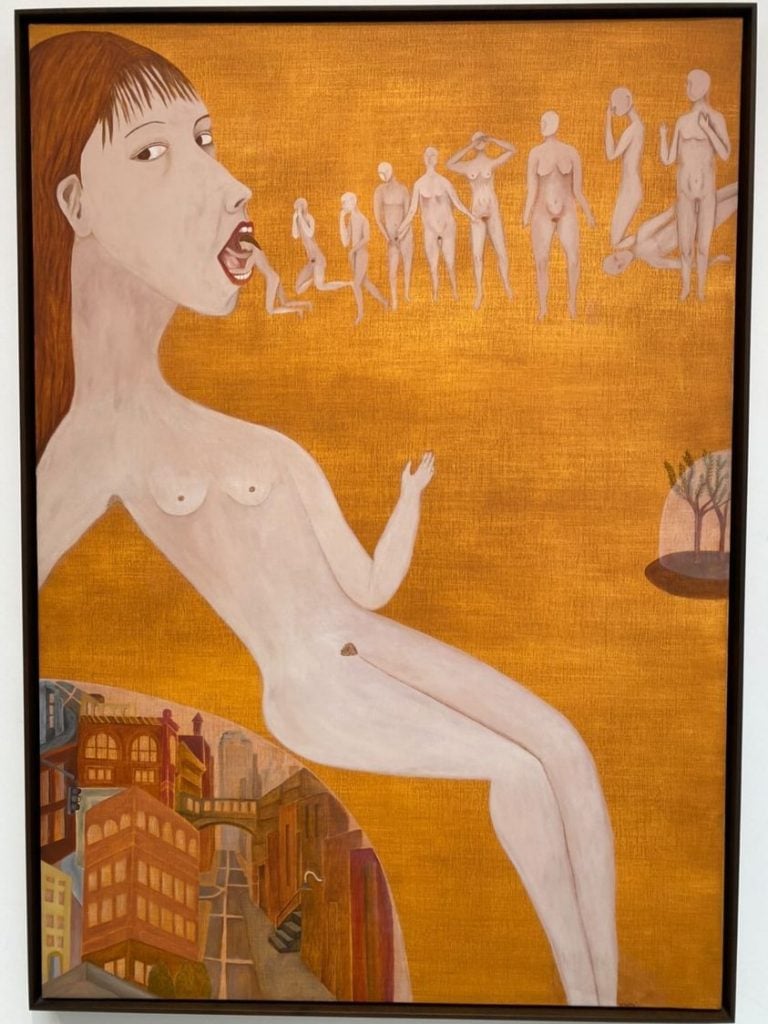

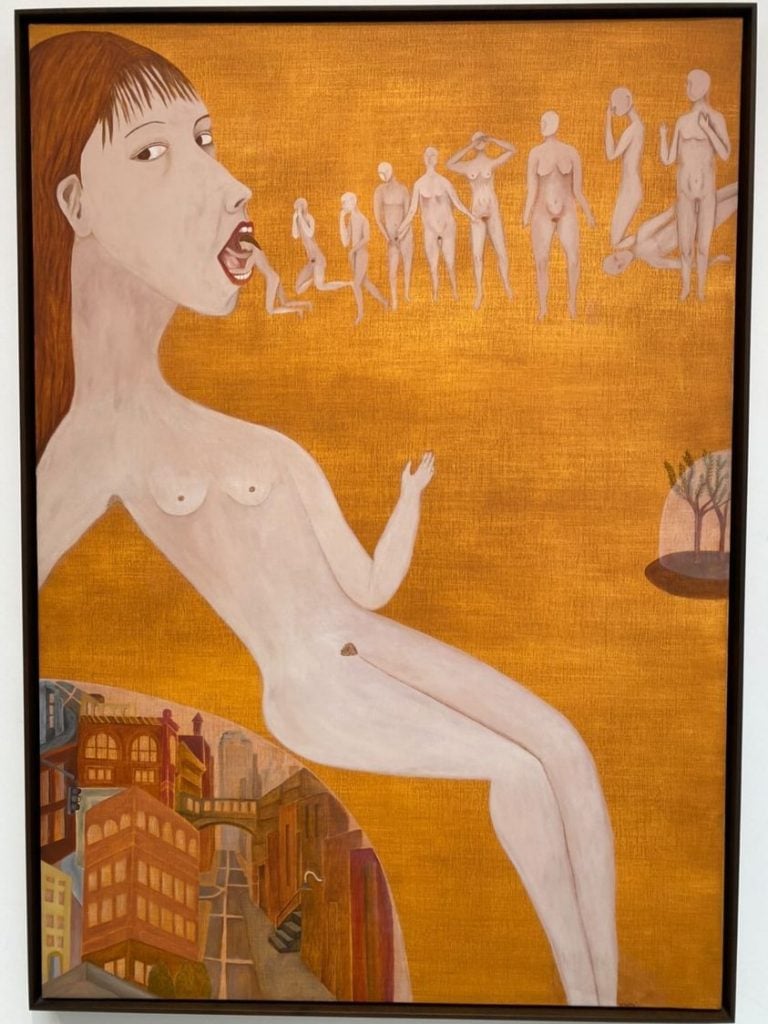

It’s not every day that you experience serendipity, but while perusing the exhibition “The Milk of Dreams” curated by Cecilia Alemani at the 59th Venice Biennale, artist Lise Grendene and I encountered just that. Standing before the painting La Comegente (The People Eater, 1971/2019), which Grendene acquired during the pandemic, we had a chance meeting with its masterful creator, eco-feminist and Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña.

Visitors to the Biennale will be familiar with Vicuña’s work Bendigame Mamita (1977) as the exhibition’s promotional image. In the central pavilion, mere feet away from that painting, rests Vicuña’s site-specific installation NAUfraga (2022) and La Comegente.

Like the rest of Vicuña’s expansive oeuvre, this lesser-known work addresses sober themes like decolonisation, through a colorful veil of sensuality. The painting features a giant-sized woman perched sitting on a modern city streetscape, as a row of faceless people pop into her mouth like so many sacrificial snacks.

Vicuña has described the work as an environmental allegory that depicts a goddess eating humans to “fertilize the earth for new people to come out.” According to curator Madeline Weisburg, La Comegente “draws inspiration from 16th-century paintings by Incan artists in Cuzco, Peru, who were forced to convert to Catholicism and both paint and worship Spanish religious icons.”

Works by Cecilia Vicuña in “The Milk of Dreams”, curated by Cecilia Alemani at the 59th Venice Biennale. Photo by Ben Davis.

After spotting Vicuña discreetly watching the crowd observe her various works, Grendene and I introduced ourselves. To my delight, the recipient of the 2022 Biennale’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement enveloped us with warmth; she is a ray of sunshine personified. Never in my career have I met an artist so completely void of pretense.

Thrilled to learn that a young female artist had acquired her beloved orange-hued ode to primordial power, Vicuña explained that La Comegente is, in fact, a reincarnation of a long-lost original. Eyes filling with memory, Vicuña told us about the start of her career in the tumultuous 1970s.

Having moved to London in 1972 to attend the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art, Vicuña left the original painting with a “dear girlfriend in Santiago, Chile” for safekeeping while she was abroad. Unfortunately, the 1973 Chilean coup d’état led by General Augusto Pinochet would force Vicuña to live in exile for most of her early career.

“Many years later, I came back [to Chile] to visit my friend, and she had hung it in the maid’s room at the back of the house,” Vicuña recalled, looking displeased at the choice of placement. Despite the perceived slight, Vicuña allowed the painting to stay in her friend’s house until she could next return.

Fast-forwarding, Vicuña continued: “When I came back the second time, she had moved. So I asked, ‘Where is the painting?’ And she just said, ‘What painting?’” Pausing for effect, she let the distressing implication of her friend’s response hang in the air.

“She’d moved to a new house and had forgotten the painting,” Vicuña stressed, her voice nearly cracking. “That’s how poorly she thought of it.” So somewhere in Santiago, Chile, there may be a discarded masterpiece by Cecilia Vicuña—check your back rooms and attics.

Aghast, I considered the painting with a renewed appreciation. In a micro sense, the tale of its abandoned predecessor illustrates the struggle artists often encounter in their early career—being dubbed irrelevant. But in the larger view, this provocative reclaiming of Indigenous female identity endured the same struggle as its subject matter—being dismissed entirely.

Cecilia Vicuña, NAUfraga (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

There is a happy ending, however. A paragon of perseverance, Vicuña recreated La Comegente in 2019, holding steadfast in her conviction that it deserved to exist. Just over five decades later, Vicuña’s self-belief has paid off, with her once discarded creation elevated to prominence at the 59th Venice Biennale.

“Vicuña has travelled her own path, doggedly, humbly, and meticulously, anticipating many recent ecological and feminist debates and envisioning new personal and collective mythologies,” Alemani remarked in a statement. It is an apropos distillation of Vicuña’s practice and oeuvre.

Vicuña’s success also speaks to the shortsightedness of her former friend, particularly from an investment perspective. An anonymous collector told Artnet News that a unique painted work by Vicuña they own has doubled in value over the past two years. With Britain’s Tate Modern recently announcing that Vicuña will take over its Turbine Hall this autumn with a special commission, one can infer that her market value will continue to rise.

Perhaps most importantly, the reincarnation of La Comegente provides an invaluable lesson to artists in the infancy of their career. “Vicuña’s story offers great inspiration and hope to young artists like myself,” Grendene said. “Especially as women looking to reclaim the female form. We can’t let the indifference of others shake our faith in ourselves.”