Art History

Cézanne Painted Mont Sainte-Victoire Dozens of Times. Here Are 3 Things You May Not Know About His Obsession With the Mountain

Japanese prints helped inspire the artist's famous series.

Japanese prints helped inspire the artist's famous series.

Katie White

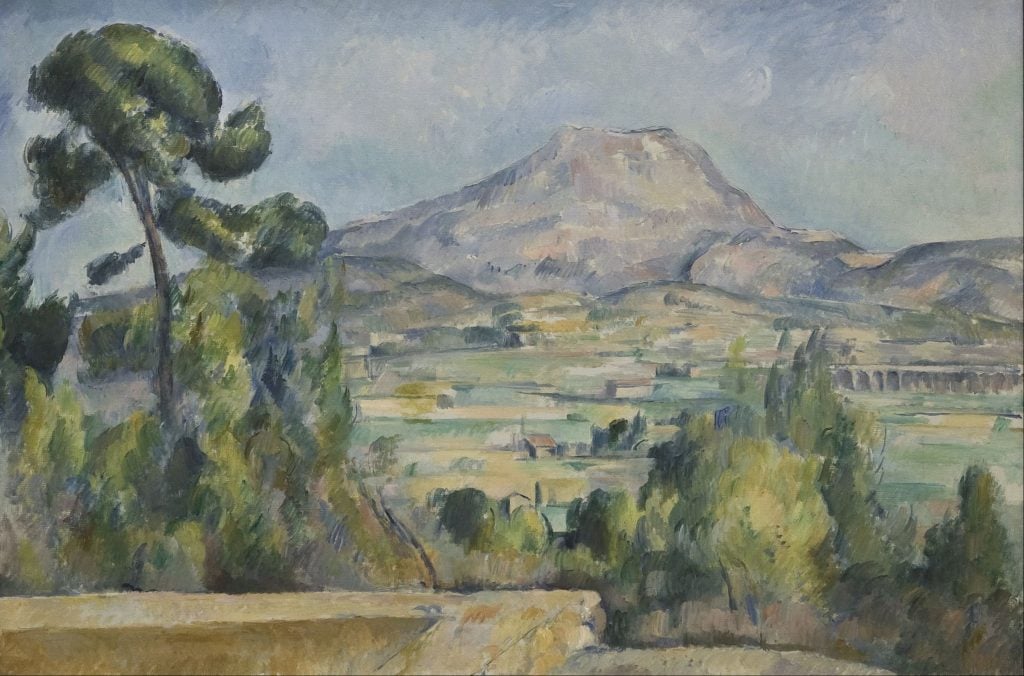

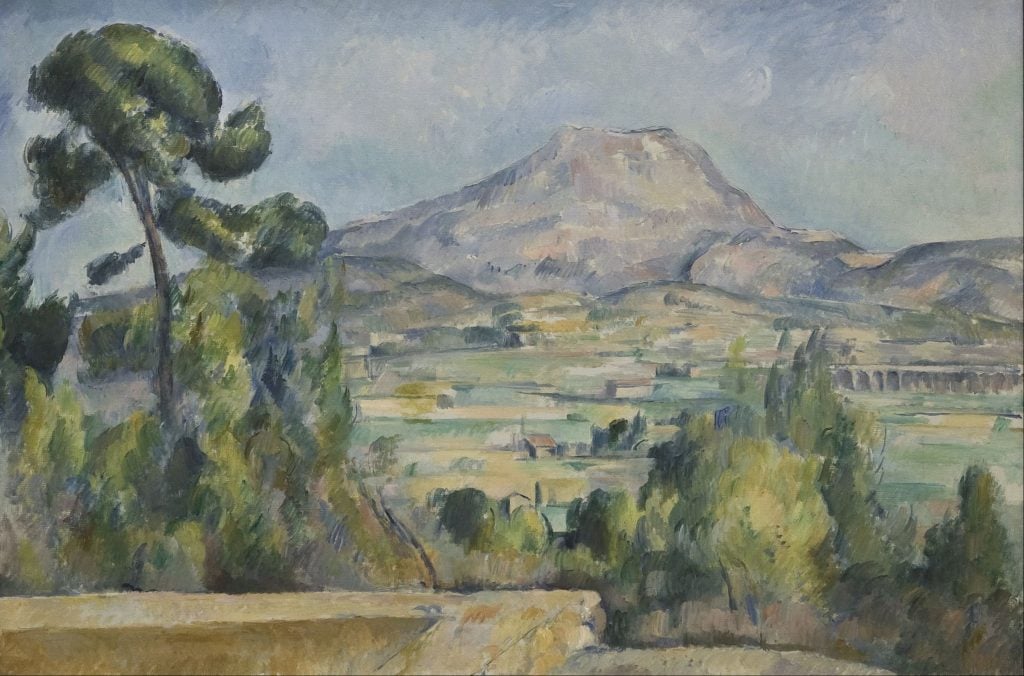

Paul Cézanne’s muse was not a person but a mountain. Montagne Sainte-Victoire, a mountain overlooking Aix-en-Provence in southern France, fascinated the visionary artist for decades, resulting in over 30 oil paintings and watercolors made over the course of his life.

The mountain, whose name means “Mountain of Holy Victory,” was by no means astoundingly large: it measures a modest 3,317 feet. But it is steeped in local and personal lore. For Cézanne, who lived most of his life in Aix, and who established a studio with a view of the mountain in nearby Les Lauves in 1902, it was a nostalgic reminder of nature’s beauty and endurance.

Paul Cézanne, Bathers at Rest (Baigneurs au repos) (circa 1876–1877). Collection of the Barnes Foundation.

The landscape first began to appearance in his works in the 1870s: he included it first in a landscape of that year titled The Railway Cutting. Then it appeared again behind as a backdrop to his Bathers at Rest (1876–77), and by 1880s, the landmark would begin to feature as a central subject.

Generally, Cézanne’s paintings of the mountain—or, more accurately, mountain range—are divided into two periods: his period of “synthesis” during the 1870s to 1895, and then his late period from roughly 1895 until his death in 1906. Despite the frequency with which Cézanne depicted the landscape, his pictures are full of unique details and surprising diversity—evidence, too, of the artist’s affection for the terrain.

A photograph of Mont Sainte-Victoire today.

Though the series is now synonymous with his oeuvre, each version holds its own nuances and surprises. In celebration of what would have been the artist’s 182nd birthday on January 19, we found three interesting facts that might make you see these paintings in a whole new way.

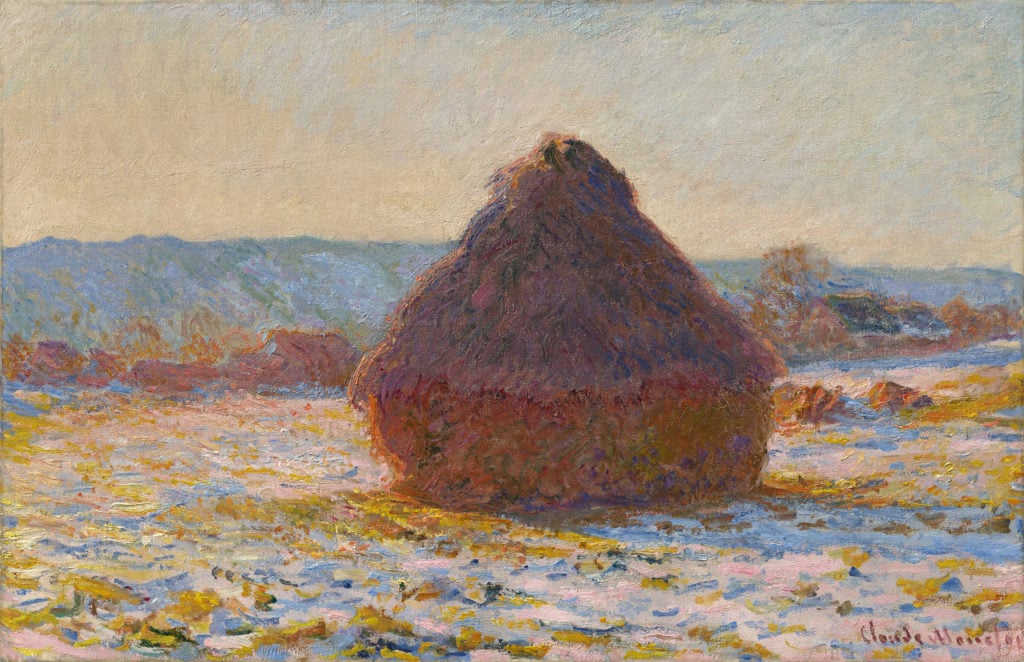

Claude Monet, Grainstack in the Sunlight, Snow Effect (1891). Courtesy Museum Barberini.

Understandably, comparisons are often made between Cézanne’s depictions of Mont Sainte-Victoire and Claude Monet’s contemporaneous “Haystacks” or “Charing Cross Bridge” works. While there certainly are commonalities—both artists were interested in the effects of light and the varied possibilities one subject could produce—there was an important and central difference to their approaches.

Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1904–1906). Collection of the Musée D’Orsay.

Monet, who was one of the few artists Cézanne truly admired, was vested in capturing the experiences of a single day. He often worked from dusk to dawn to complete a painting. Cézanne, on the other hand, labored over his canvases of Mont Saint-Victoire often over a period of years, and sought to capture the mountain not specifically within a time or a season, but on an atemporal plane.

This was especially true of the artist’s late paintings, such as the version in the Musee D’Orsay. Here, Cézanne has moved away from his earlier Impressionistic style, with its emphasis on transience, and cultivated his Post-Impressionist innovation, instead placing emphasis on the relationships between color, form, and emotion as a kind of enduring structure. Mont Sainte-Victoire, with its sense of permanence, offered the artist the perfect subject for these new artistic interests.

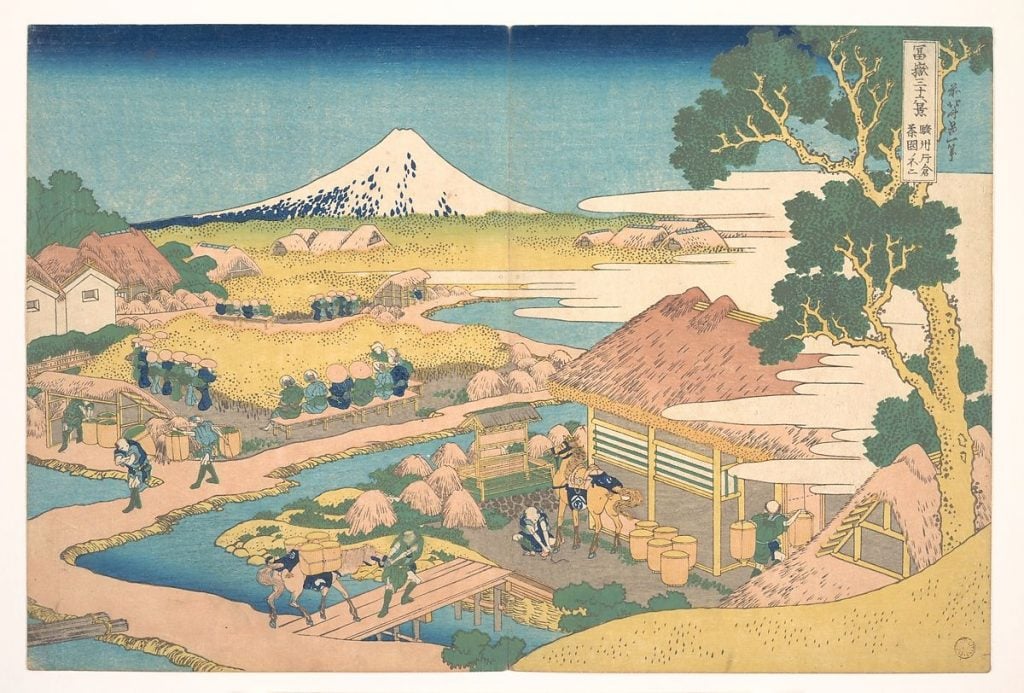

Katsushika Hokusai, Fuji from the Katakura Tea Fields in Suruga from the series “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” (1830–1832). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One thing Cézanne’s many depictions of Mont Sainte-Victoire share is an aerial, birds-eye perspective. This strategy, many art historians believe, was directly inspired by Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, which were wildly popular in France at the time.

In 1913, the German art historian Fritz Berger first noted that Cézanne’s approach to perspective might seem to be inspired by 19th-century Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige’s series of wood prints “Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido” from the mid-1800s. Though many believed that Japonisme in Cézanne’s work was primarily filtered through the influence of Monet, the art historian Hidemichi Tanaka argues otherwise, noting that Camille Pissarro, Cézanne’s mentor, was familiar with Hiroshige prints and likely introduced them to Cézanne directly.

Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire(1904-1906). Collection of the Musée D’Orsay.

What’s more, Cézanne was known to have studied contemporaneous art historian’s Joachim Gasquet’s books on both Japanese artists Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai. Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” stand as an obvious parallel to Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire series.

“It was not just the composition of Mont Sainte-Victoire paintings but also the very idea of a series of views of a specific mountain which seem to have been derived from Hokusai’s view of Fuji. Before Cézanne, no European had executed a long series of views of a single mountain,” Hidemichi Tanaka writes.

Yet Cézanne’s approach was not without innovation. In fact, whereas Ukiyo-e prints depended by their nature on the strength of outlines, Cézanne adopted a “tache” approach, in which distinct lines are all but done away with.

Maurice Denis, La visite à Cézanne. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The majority of Cézanne’s depictions of Mont Sainte-Victoire come from the last years of the artist’s life: 1902, when he established his studio in Aix, until his death in 1906. By those years, the artist, who had been rejected from salons earlier in his life, was already beginning to be heralded as one of the great artists of his generation.

Simultaneously, however, Cézanne had begun to retreat from public view, living almost hermetically (save visits from other artists) in the mountains. And as the artist’s living legend grew, so too did his association with the mountain itself—and not without the artist’s own mythologizing.

Indeed, Cézanne emphasized a kind of cosmic connection to the mountain—the historian Joachim Gasquet recalled of a conversation in which Cézanne purportedly exclaimed: “Look at Ste.-Victoire. What élan, what an imperious thirst for the sun, and what melancholy, in the evening, when all this weightiness falls back to earth… These masses were made of fire. Fire is in them still.”

Cézanne, who had struggled through periods of great depression and doubt throughout his career, continued to paint, but shut off from the world, his depictions of Mont Sainte-Victoire became a kind public stand-in for the artist himself—inaccessible, distant, but nevertheless admired.