Art & Exhibitions

Ben Davis on Why Charles Ray Is a Brilliant Sculptor But Occasional Creep

Ray is celebrated for this type of work. Why?

Ray is celebrated for this type of work. Why?

Ben Davis

There’s a good and a bad way to feel weird, and the Charles Ray retrospective currently at the Art Institute of Chicago made me feel both of them.

Ray specializes in a peculiarly deadpan kind of sculptural craziness. His best sculptures are both sensuous and brainy, viscerally appealing and pleasantly challenging.

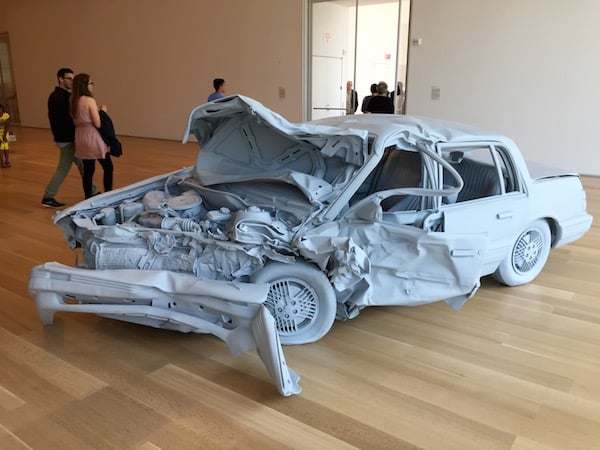

Charles Ray, Unpainted Sculpture (1997).

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Davis.

The works in this exhibition that show off the artist at the peak of his powers are Unpainted Sculpture (1997), a meticulous, matte gray cast of a wrecked car, or Hinoki (2007), a one-to-one simulation of a fallen tree, recreated by Japanese wood carvers. Both have an intricate formal beauty that is all the more unsettling given that he uses his subject matter as proxies for thoughts about death and decay.

Charles Ray, Hinoki (2007).

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Davis.

As I said, Ray is celebrated for this type of work—so celebrated that I won’t waste a lot of time praising it. Let’s skip on over to the other side of weirdness in this show.

The Art Institute is offering just 19 sculptures in all, focusing on the more recent decades of Ray’s career, when he turned away from the kind of formalist-conceptualist jokes that made his name (my favorite: Ink Line (1987) a sculpture that appears to be a black wire hung floor-to-ceiling but is actually a thread-like waterfall of perpetually circulating ink) to that most uncool of sculptural things: representations of the human figure.

The results betray an interest in the frozen naturalism of classical Greek sculpture. They modernize the antique reference, though, by playing with scale in deliberately odd and estranging ways and using state-of-the-art fabrication to create forms that feel almost off-putting in their limpid perfection.

Charles Ray, Horse and Rider (2014).

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Davis.

The subject matter is often self-portraiture (Horse and Rider (2014), a life-size, shiny aluminum equestrian sculpture shown in the garden outside the museum, featuring a slouching, aged Ray) or portraits of people with whom Ray is intimately familiar (Aluminum Girl (2003), a white-painted, diminutive nude figure of Jennifer Pastor, a former student and lover).

Charles Ray, Aluminum Girl (2003).

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Davis.

And then there are the ones where he branches outside of his circle of studio concerns to deal with broader human subject matter, and that’s where things start to feel really weird.

One of these—the centerpiece of the show, though shown in a small-ish gallery off to the side—is Huck and Jim (2015), which achieved some notoriety because it was commissioned for the new Whitney Museum of American Art in downtown New York, then rejected as inappropriate for a public venue.

It portrays two figures from Mark Twain’s 1885 novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which is quintessentially American in both its folksy humanism and in its continuous ability to generate controversy over its depiction of Jim, a runaway slave. In Ray’s rendering, both figures are larger-than-life, nude, and white.

Charles Ray, Huck and Jim.

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Davis.

An adult Jim has a look of blankly heroic vigilance, with one hand hovering over the back of the bent-over figure of Huck, who is only 13 years old in the novel.

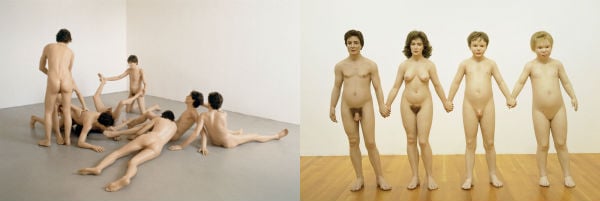

Sexual taboo is a pretty consistent theme for Ray. Consider some of his greatest hits (not featured here): Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley… (1992), his self-portrait as eight identical mannequins furiously masturbating and fellating one another, or Family Romance (1993), his sculpture of an archetypal Anglo nuclear family, all nude, but with the pre-adolescent boy and girl blown up to match the size of the parents, to creepy effect.

Left: Charles Ray, Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley… (1992); Right: Family Romance (1993).

So, it seems fairly obvious that what Ray has done in Huck and Jim is to take the eternally disputed racial politics of Huckleberry Finn and cross them with a dash of Death in Venice. The classical Greek reference only makes it seem more like a knowing riff on the idea of “Greek love.”

That theme is clear without the sculpture coming out and proclaiming it, so to speak—which is to say it’s not clear what this meticulously conceived sculpture is doing with all those hot-button issues besides mashing at them. I guess in one way the sculpture is about insinuation.

Thus, instead of explaining what is going on, the wall text practically stammers, both acknowledging and not acknowledging it: The duo’s nudity, we are told, both suggests the innocence of a “state of nature” but is also “fraught with tensions and ambiguities.” Ray is quoted as saying that the sculpture is about “desires fulfilled and unfulfilled.”

Still, it is another sculpture, from a group of three figurative works first seen at Matthew Marks gallery in New York in 2012, where for me Ray’s studied coyness really runs aground.

Charles Ray, Sleeping Woman, (2012).

Photo: Courtesy of Ben Davis.

Rendered in solid stainless steel, Sleeping Woman depicts a homeless African-American woman sleeping awkwardly on a bench. The label compares her pose to that of a “goddess from antiquity.” Here’s a passage from the wall text:

Ray was inspired to create this work when he encountered a woman sleeping on Wilshire Boulevard in Santa Monica, California. After being immediately struck by her uncanny ability to doze amid the noise and activity of a busy street corner, he returned to photograph her an hour later, and she was still asleep. Silently studying this unlikely muse, the artist discovered a beautiful face framed by unkempt hair. Her curled position stretched her pants, pulling the elastic lace of her underwear into public view and exposing the small of her back along with parts of her shirt and jacket.

To which you have to say: Wow, Ray sounds like a real creep.

An artistic discourse—and here I’m talking about both Ray’s and that of the author of this text—that cannot see how sketchy this sounds is one so locked inside its own ice-cold intellectual concerns as to become almost inhuman.

You could imagine justifying such a sculpture by saying that it was about giving a sense of dignity to one of society’s least fortunate. But the entire thrust of this passage is to depict how Ray specifically reduces this woman to an object, an insensate body that he happened upon, with a certain degree of latent pathos and formal complexity (“the elastic lace of her underwear!”) that makes it ripe for appropriation as an image, no different than a wrecked car or a fallen tree.

In an interview with Bomb, Ray once said that he tries to conjure a sensation “between the genitals and the head.” You get what he’s saying. But one thing that is actually between the genitals and the head is the heart. In a work like Sleeping Woman, the heart seems to be missing, and Ray doesn’t seem to know it.

“Charles Ray: Sculpture, 1997-2014” is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago, through October 4, 2015.