Art History

This Delightful Trick Painting Is a Treasure of Early U.S. Art. Here Are 3 Facts About the Philadelphia Museum’s Beloved Trompe L’oeil

Charles Willson Peale's 'The Staircase Group' is full of surprises.

Charles Willson Peale's 'The Staircase Group' is full of surprises.

Katie White

Eighteenth-century American artist Charles Willson Peale is today best remembered for his portraits of Revolutionary War figures, including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and George Washington (of whom he painted some 60 portraits). But Peale’s own interests and talents followed many more unexpected avenues than portraiture alone.

Born in 1741 in what is today Maryland, Peale was known in his lifetime as a soldier, a scientist, an inventor, a naturalist, and, the title most important to him, an educator. His youth was marked by experimentation; Peale had tried his hand as a saddlemaker and then a clockmaker (finding little success with either), before ultimately making his way to painting, studying with John Singleton Copley and then Benjamin West.

Peale moved to Philadelphia in 1776, the city he would make home for the rest of his life. Today, the Philadelphia Museum of Art counts Peale’s The Staircase Group (1795)—a trompe-l’œil painting of two of his sons Raphaelle and Titian (who were, yes, named after the artists)—as one of the collection’s cornerstones. Here, the two sons, clad in the fashions of the times, are shown ascending a narrow stairway that is adorned in ornate wallpaper. The sons turn to back to gaze down the stairs and towards the viewer as though to invite them along on their journey. One real step is adjoined to the base of the canvas, bringing Peale’s optical illusion into real space.

In honor of the July 4th holiday, we’ve taken a closer look at this curious and delightful painting. Here are three facts you might find surprising—and informative.

Charles Willson Peale, The Staircase Group (1795). Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Originally, Peale’s portrait was known as Whole Length–Portraits of Two of His Sons on a Staircase. While that title might not particularly captivate the imagination today, it is nevertheless revealing.

Even into the 19th century, full-length portraits were typically reserved for depictions of the aristocracy, religious figures, and occasionally war heroes. It would have been conspicuously unusual, then, the see Peale’s full-length portrait of his eldest son Raphaelle.

Raphaelle was, by this time, already a successful painter in his own right. Here he is shown holding the tools of his trade, a palette, and brushes, much like a saint with his attributes.

Peale’s choice of subject matter was highly intentional. The Staircase Group was painted specifically for an exhibition mounted in the Pennsylvania State House in 1795 that marked the establishment of the Columbianum, the nation’s first art academy. Peale had been instrumental in organizing the school’s founding, believing it essential that aspiring American artists be able to be trained in Philadelphia rather than journeying to European academies.

This exhibition, in some senses, wanted to underscore already existing American artistic accomplishments. Among the 150 works on view were a number of paintings by the youthful Raphaelle Peale himself. In this light, Raphaelle’s confident depiction on the staircase takes on a new meaning: The American artist was—quite literally—on the come-up.

Detail of The Staircase Group (1795) by Charles Willson Peale.

Here’s a revealing detail: A paper note seems to have fallen from one of the son’s pockets onto the staircase.

While the device emphasizes the realism of the scene (the urge is to reach out and pick it up), a closer look reveals that it is an entrance ticket to Peale’s Museum (though the ticket is hard to make out, viewers in 1795 would have recognized it at the original showing). Believing that education was the backbone of a healthy democracy, Peale had established his own museum at Philosophical Hall, in a building next to the Pennsylvania State House (today known as Independence Hall).

Charles Willson Peale, The Artist in His Museum (1822). Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of Art.

His museum was not an art museum in the sense known today, but one he referred to as “a world in miniature.” There, he displayed not only his many portraits of famed civic leaders, but all manner of scientific and natural specimens from inventions to fossils, and taxidermied animals and insects. The price of admission was marked at 25 cents.

Considering that it would have been possible actually to see the museum from the Pennsylvania State House, some historians believe that Titian’s gesture pointing up the stairs is directing viewers to his father’s museum.

Charles Willson Peale, George Washington (ca. 1779–81). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Peale’s painting remains surprisingly effective even today. Part of the realism of his illusion is created by the real door frame that surrounds the canvas, along with the physical step that juts out from the base of the painting. The Philadelphia Museum notes that “many viewers have been fooled into thinking that these are real people standing in a real staircase.” Among the many to have fallen to the trick was George Washington himself, at least according to Rembrandt Peale, another of the artist’s sons.

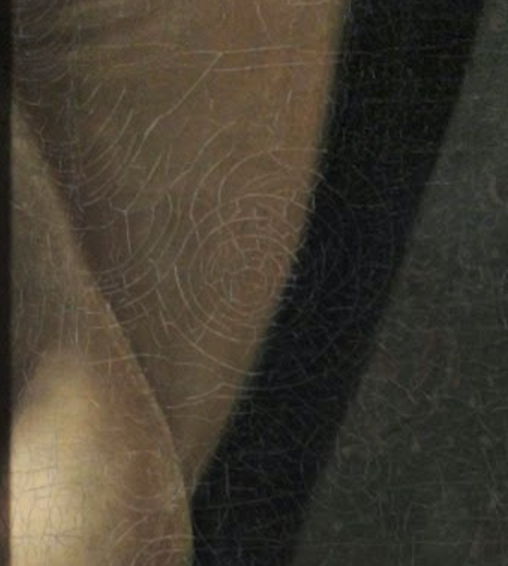

Details of the circular craquelure on the surface of The Staircase Group.

“I observed that Washington, as he passed it, bowed politely to the painted figures, which he afterward acknowledged he thought were living persons. If this homage bestowed on the pictures was not indicative of its merit, it was, at least, another instance of habitual politeness,” he wrote in his article “The Person and Mien and Washington,” published in the literary journal Crayon.

More recently scholars have debated the veracity of Rembrandt’s tale, as according to art historian Wendy Bellion, “his account followed a literary convention that celebrated artists who deceived authority figures.”

Still, the legend of this encounter is not without its elements of truth, however. The painting itself testifies to its own success; its surface is covered in impressive webs of circular craquelure—a conservation issue caused, in most cases, by people reaching out to touch a canvas. If that’s any evidence of Peale’s trompe l’oeil talents, Washington was in excellent company.

Details of the circular craquelure on the surface of The Staircase Group.