Law & Politics

Chicago Has Launched a Street Art Registry to Prevent Beloved Murals From Being Inadvertently Destroyed

The database, already populated with 150 works, allows people to learn more about the city’s murals and the artists behind them.

The database, already populated with 150 works, allows people to learn more about the city’s murals and the artists behind them.

Taylor Dafoe

For as long as there have been buildings and spray cans, the line between art and graffiti has been murky. But now, in Chicago at least, that line has become a little clearer.

Last week, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events launched an official Mural Registry, a new program that protects street artworks on private and public property and compiles them in a public database.

Artists are encouraged to apply to have their work included in the database, and those applications are reviewed and approved by a three-person team within the Department of Cultural Affairs. The murals must be commissioned or sanctioned by the property owner, so fly-by-night taggers are not eligible.

Each approved mural receives an official emblem from the City of Chicago installed on or near the work and will be entered into the public database, where visitors can learn more about the artwork and who created it.

The registry was developed partly in response to at least three incidents last year in which city sanitation crews, tasked with cleaning up the city at the prospect of Amazon moving in, mistakenly painted over commissioned murals.

One such work, a painting by French artist Blek le Rat, was owned by the company Cards Against Humanity, whose headquarters are in the city’s Logan Square area. Following the episode, Cards Against Humanity’s founder Max Temkin worked with local artists to propose an ordinance that would protect city-certified art.

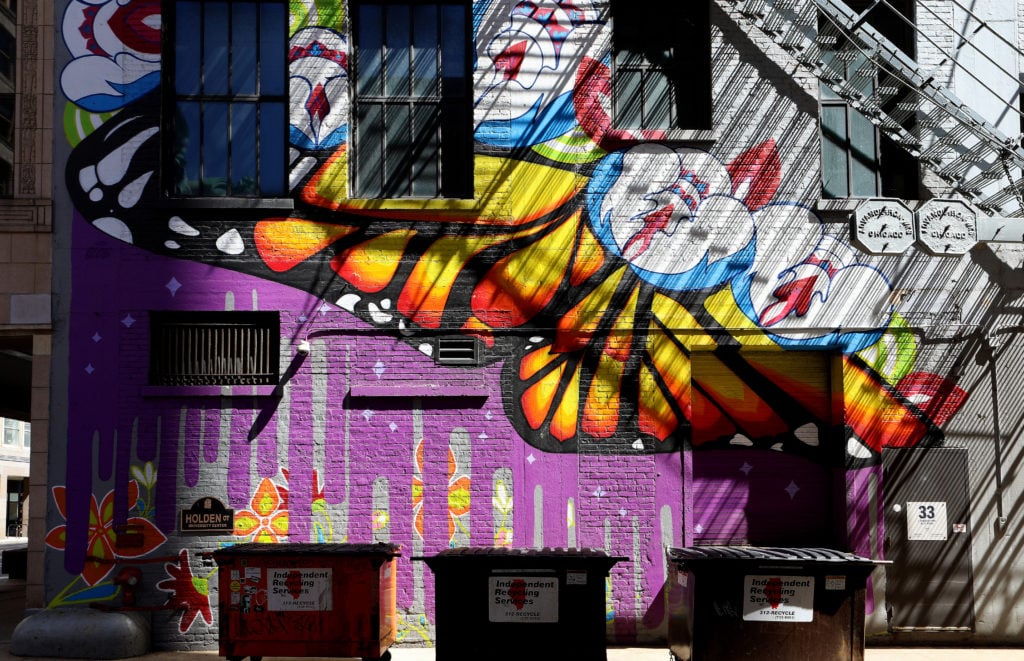

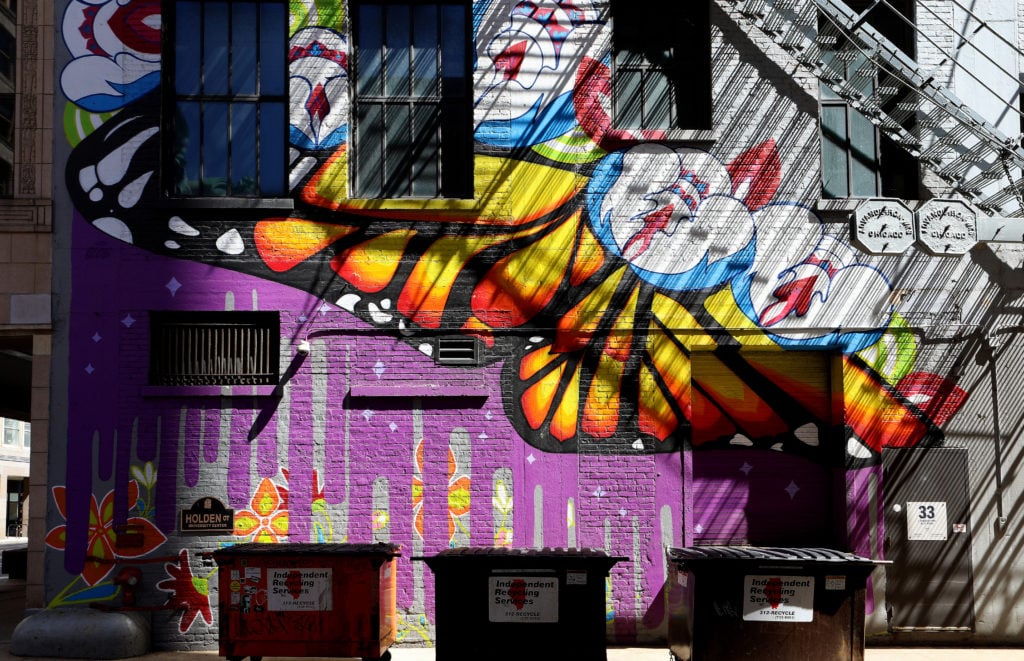

Lady Lucx and Sarah Stewart’s untitled mural, part of the Wabash Arts Corridor is displayed downtown in Chicago in 2019. Photo: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images.

The criteria for approval is rather straightforward, explains Mark Kelly, the commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events.

“We are not becoming art critics and deciding what is art and what is great art,” Kelly tells artnet News. “What we’re looking for is that the work is in reasonably good condition. It has to be art in that it’s not a sign, it’s not marketing anything, and it can’t have any offensive material—gang symbols or anything that one would deem offensive in the public realm. But short of that, it’s approved.”

Kelly notes that while there’s no way to tell how many murals exist on Chicago’s streets, he’s sure the number is well into the thousands. So far, 150 have been approved by the registry.

The database isn’t mandatory for murals; if an artist would prefer not to include their work in the registry, the department will respect that. “But why wouldn’t an artist want to comply?” Kelly asks. “We protect the work and it also becomes available in the database for people to learn more.”

Of course, bureaucratic red tape isn’t going to be welcomed by all street artists, a group largely known for embracing the illegal and the ephemeral as tenets of their medium. Yet, for Kelly, the registry will nonetheless expand the city’s public art landscape.

“I want more public art,” the commissioner says. “This isn’t just to protect where we are now; this is to help everyone to understand what’s out there and to become inspired by it and to create evermore.”