Art World

Christian Jankowski Guest-Starred on a German Crime Drama and Declared It Art. The Producers Say, No, It’s Just a TV Show

The artist appropriated the episode for his latest exhibition at Petzel Gallery in New York.

The artist appropriated the episode for his latest exhibition at Petzel Gallery in New York.

Henri Neuendorf

An exhibition at a Chelsea gallery has become a new battleground for an age-old question: Is an artist ever allowed to take another person’s work and re-present it as their own?

The question takes on new meaning in a dispute between the German artist Christian Jankowski and the producers of a German television show, who are displeased that Jankowski has presented an episode he appeared in as his own work in his latest solo show at New York’s Petzel Gallery (on view through August 3).

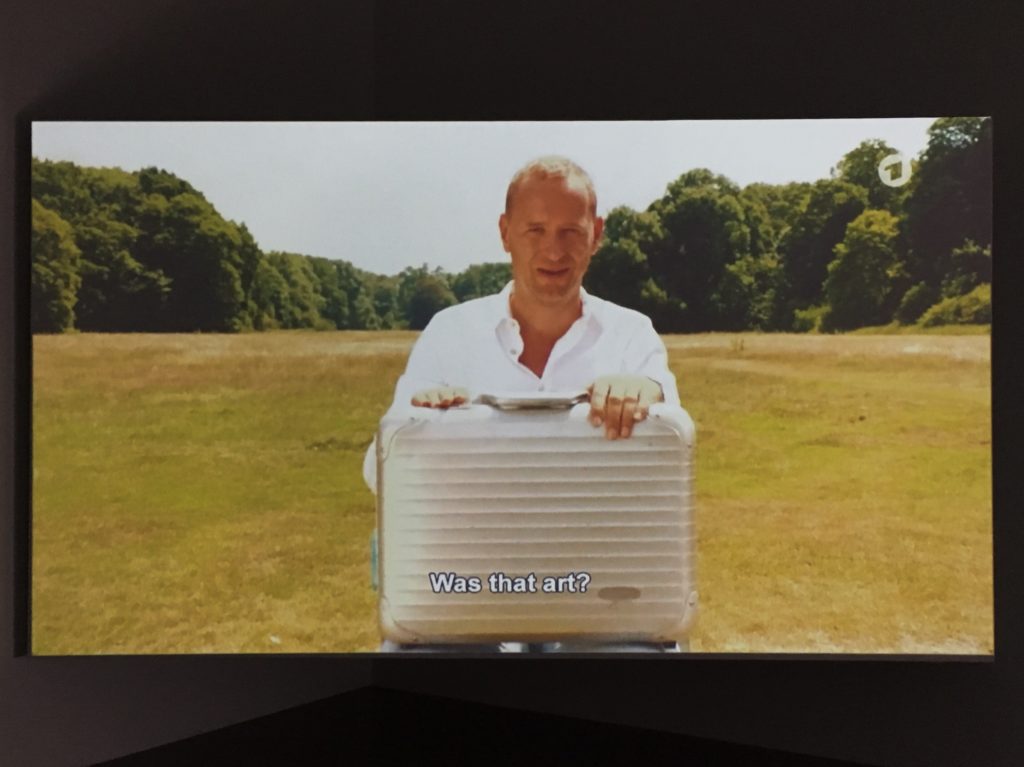

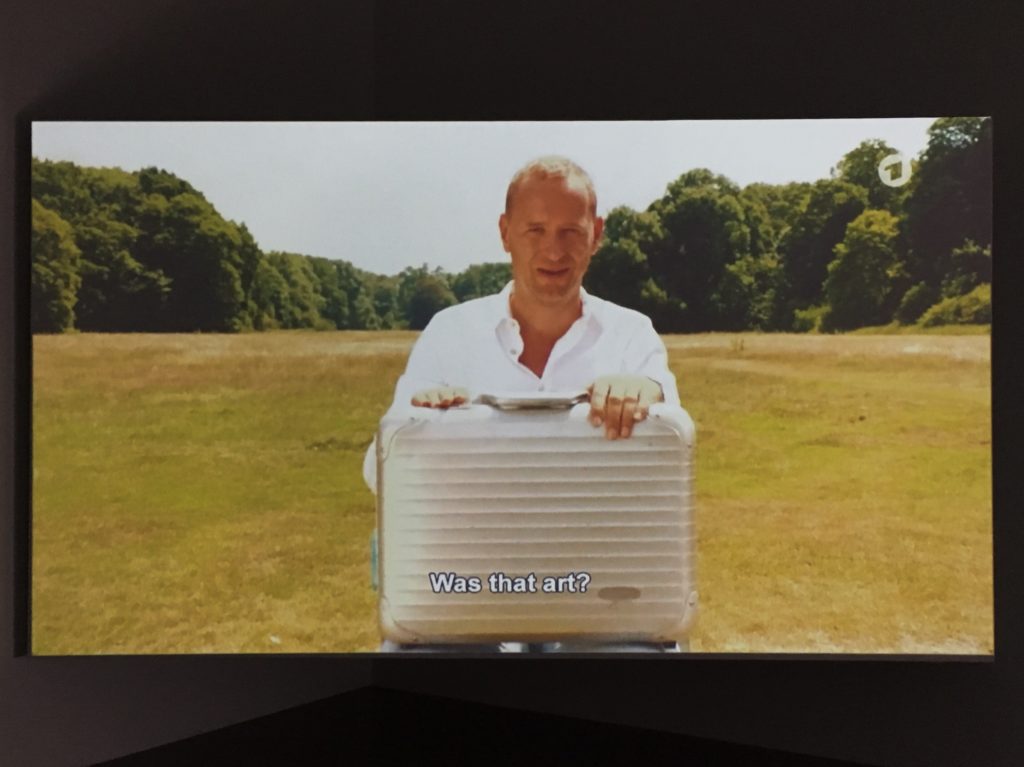

Last year, the producers of the popular television crime series Tatort—a kind of German CSI—dedicated a special episode to the Skulptur Projekte Münster, a sprawling sculpture exhibition that takes place in the German town of Münster every 10 years. Jankowski guest-stars as an eccentric artist and suspect in a grisly series of murders. There’s just one problem: Jankowski is presenting the episode in his latest exhibition as his own artwork, while the show’s producers don’t believe he has the right to do so.

Tatort (which means “crime scene” in German) holds a special place in German society. The long-running crime show has aired every Sunday evening since 1970; millions of Germans end their weekends with the show. Like the popular American procedural CSI, it follows a basic format: detectives investigate crimes in different German cities that are always resolved by the time the credits roll. In the Münster episode, a vigilante artist goes on a killing spree, using his victims as material for his sculptures.

Jankowski plays the character Jan Christowski, a minor supporting role (with a not-so-subtle twist on his real name). Additionally, a spokeswoman for Petzel says, “Christian provided some basic parameters around the… production. The screenwriters wrote the plot of Tatort themselves, but they were of course influenced by Christian.”

The Tatort episode featuring Jankowski was broadcast on the German TV station ARD in November 2017 and is presented in its entirety at Petzel’s Chelsea gallery, albeit with English subtitles. The video is being offered in an edition of five (plus two artist’s proofs) for €25,000 ($21,500) each, according to a gallery representative. At the time of writing, none had sold.

In an email, the German producers behind the show, Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), told artnet News that they did not sanction Jankowski’s screening of the episode and appear to have been unaware that the artist had moved ahead with his plan to present the work as his own.

“I assume there is some sort of misunderstanding and that he only told you about his intentions, and for legal reasons did not follow through [with the screening],” a spokesperson for WDR writes. The producers maintain that they invited Jankowski to participate and that the episode, titled “Gott ist auch nur ein Mensch (Even God Is Only Human),” remains their property.

The producers’ comments, which at some points resemble a technical treatise on the nature of creation, underscore the elusive, slippery nature of conceptual art. “Although the Münster episode… includes Christian Jankowski’s work, it is not part of Mr. Jankowski’s work and cannot therefore be presented within an exhibition or solo show,” the spokesperson says. “In our view a screening would be misleading, perhaps even alienating.”

Jankowski presented a very different version of events in a conversation with artnet News. The artist says he is the one who conceived the idea for a special edition of the show set at Skulptur Projekte Münster. The collaborative production, he claims, was also intended to serve as his contribution to the exhibition. (Due to delays, the show ultimately did not air until November, a month after the show ended. Münster’s curator Kasper König did not respond to a request for comment.)

“From my perspective, it is my artwork because I came to them [WDR] with the idea,” Jankowski says. “I pitched that I would play as myself in the fictional story of Tatort taking place during the Sculpture Projects.”

Ahead of the screening at Petzel, the artist says he was in negotiations with WDR and was ready to pay for the rights to screen the film; he also claims his contract included a clause stating that he would receive five copies of the film provided the producers didn’t object. But 10 days before the opening on June 28, WDR recanted and suddenly barred him from showing the work. He says the bureaucratic structure of the publicly-owned station made it impossible to find a compromise, so he decided to proceed with his original plan.

“I always said it was also an artwork,” Jankowski insists. “It is not only an artwork, but many different things. If I don’t place this in the art world then I wouldn’t be standing behind my work, and I decided I have to stand behind my work.”

The controversy has raised some thorny questions surrounding appropriation, authorship, and the relationship between the art world and entertainment. Can an artist claim a TV show he guest-starred in as his own work if he shows it in a gallery context? Can mainstream television ever be seen as art? And in an era of collaboration, can copyright rules truly determine who created a work?

“I’m quite aware that I like to operate on the boundaries, and I have nothing against the discussions about what is art or not,” Jankowski says. “All of my work is based on performance and there’s a notion of involving other authors; multiple authorships are the basis of my art.”

The artist emphasized that his role was far greater than simply appropriating a TV show he appeared in. “It’s more complex than that,” he insisted. “Of course I didn’t do it as an independent artwork in a studio where I’m god and can control the materials. I work with vast commercial, political, and religious structures in my work and this compromise between worlds defines the shape of my artworks.”