Art & Exhibitions

Here’s What You Need to Know About Chicago Imagist Christina Ramberg and Her ‘Furtive Figuration’

The Art Institute of Chicago presents "Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective," nearly three decades after the artist's untimely death.

The Art Institute of Chicago presents "Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective," nearly three decades after the artist's untimely death.

Annikka Olsen

“My aim is to make from my obsessions and ideas the strongest, most coherent visual statement possible,” artist Christina Ramberg once said, describing her process and intentions.

Closely affiliated with the Chicago Imagists, a loose group of artists formed in the mid-1960s who favored representation and bold aesthetics, Ramberg (1946–1995) produced a powerful body of work with a distinctive personal style during her comparatively short life and career.

Ramberg’s work is immediately recognizable, primarily focused on figural elements of the female form—such as hands, hairstyles, garments, and, most notably, torsos—and rendered in a graphic and highly stylized aesthetic. Tapping contrasting themes and ideas and embracing experimental modes of framing and cropping, Ramberg forged an intrepid path along the boundary between abstraction and representation.

Installation view of “Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective” (2024). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Heralding a resurgence of interest and critical attention to Ramberg’s singular oeuvre is the exhibition “Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective,” on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through August 11, 2024—the first comprehensive survey of her work in nearly three decades. Bringing together roughly 100 works from the Art Institute’s collection as well as from other public and private collections, the show traces her evolving style from early paintings that explored pattern and form through to her mature (and most recognizable) works that feature female torsos, lingerie, and restraints.

Marking this pivotal retrospective, we took a deep dive into Ramberg’s life and work, and below are (just) the essentials you should know about her practice.

Installation view of “Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective” (2024). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Early Inspirations

Even while still a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), Ramberg’s fixation with elements of the human body—namely hair, hands, and women’s garments—was evident in her work. Studying under some of the institution’s most historically influential teachers, including Ray Yoshida, a primary mentor of what would become the Chicago Imagists, Ramberg along with her classmates produced work that focused on what the present retrospective terms “furtive figuration.”

Christina Ramberg, Belle Rêve (1969). Photo: Jamie Stukenberg. © The Estate of Christina Ramberg. Collection of Michael J. Robertson and Christopher A. Slapak.

This approach to figuration first fully coalesced in a series of student exhibitions with SAIC as well as in two exhibitions, “False Image” and “False Image II,” organized by Ramberg and fellow students in 1968 and 1969 at Chicago’s Hyde Park Art Center. “We are interested in the effects gained by withholding information in a work,” Ramberg told the Chicago Daily News while describing the ethos of the work created by the False Image exhibition artists. And withhold her work did.

Christina Ramberg, Hair (1968). Photo: Kris Graves. © The Estate of Christina Ramberg. Collection of Joel Wachs, New York.

An isolated bustier, a cropped foot in a heeled shoe, or, most well-known from the period, depictions of women’s heads from behind, with only the details of their hairstyle shown, Ramberg’s early works were nearly as recognizable for what they showed as for what they didn’t. Within the context of Ramberg’s oeuvre, they foreshadow the artist’s creative trajectory and the themes and motifs that ultimately served as the foundation for her most important works.

Iconic Forms

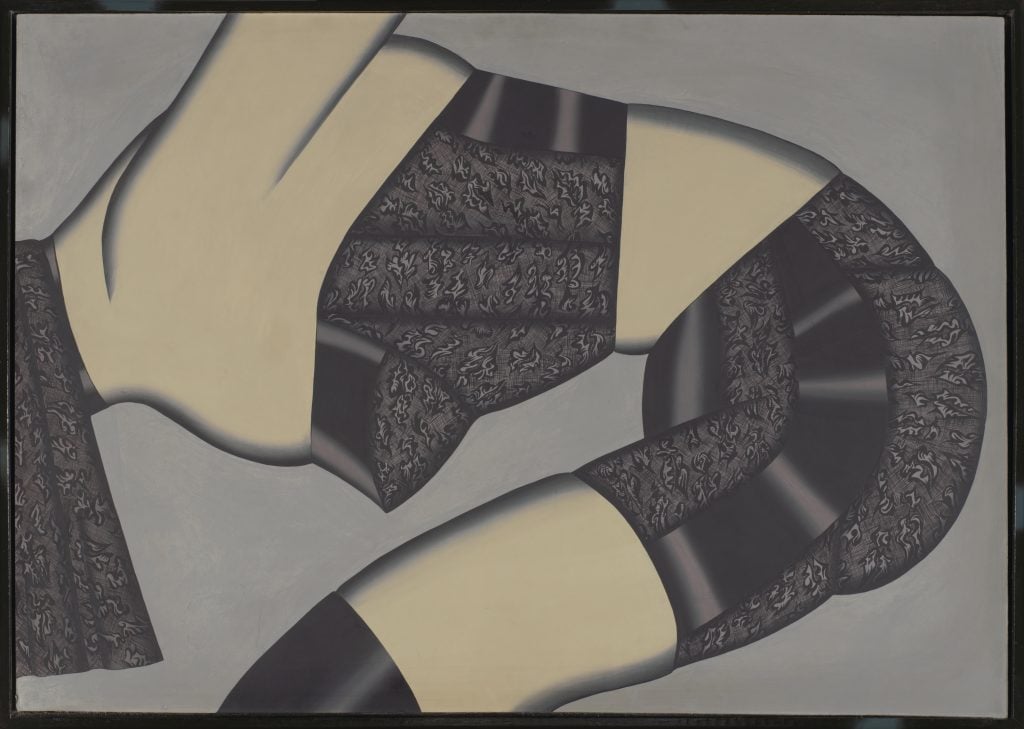

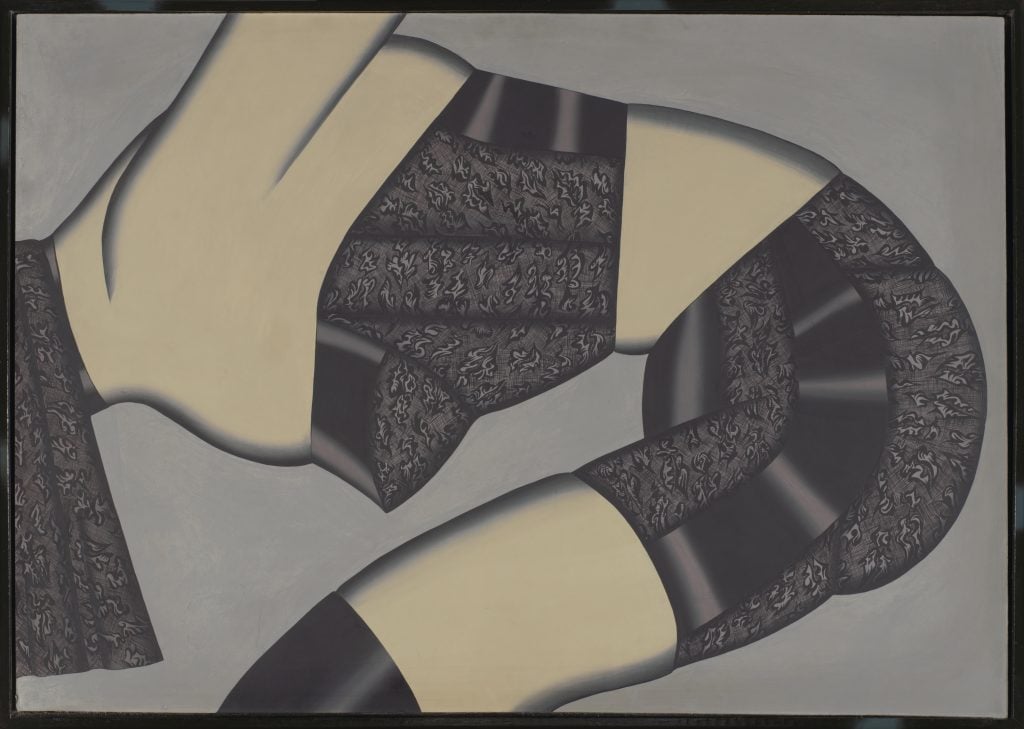

The 1970s saw Ramberg produce her most iconic body of work. Continuing her exploration of isolated body parts and their configuration, which can be traced in her meticulous sketches and studies of hands, the feminine elements of her work took a turn to the risqué. Corsetry and black lace, brassieres and other lingerie coupled with suggestive poses as well as hands in contorted shapes with carmine-painted nails—and never featuring the subjects’ face—each of Ramberg’s compositions allude to the various ways women’s bodies can be shaped and fashioned.

Christina Ramberg, Probed Cinch (1971). Photo: Clements/Howcroft, Boston. © The estate of Christina Ramberg. Private Collection, New York.

Ramberg’s memories of watching her mother dress informed the works, with Ramberg describing “… I think that the paintings have a lot to do with this, with watching and realizing that a lot of these undergarments totally transform a woman’s body … I thought it was fascinating … in some ways, I thought it was awful.”

Operating along the line between “fascinating” and “awful,” Ramberg’s paintings are at once uncanny and sensually alluring, tapping into the language of fetishism.

Christina Ramberg, Black ‘N Blue Jacket (1981). Photo: Jamie Stukenberg. © The Estate of Christina Ramberg. Collection of Kathy and Chuck Harper, Chicago.

As her practice evolved, however, Ramberg’s figures became less erotic—and less human overall. Pieces from the late 1970s and early 1980s once again feature her signature cropped female torsos but they instead appear robotic, and even diagrammatic; the core elements of painting, such as color, line, shape, and more specifically their precision (a facet of work she had then become most well-known for) became as much the subject of her work as the figures depicted.

Artist as Collector

Although Ramberg is best known for her paintings, a consideration of her oeuvre would be incomplete without mentioning her penchant for collecting.

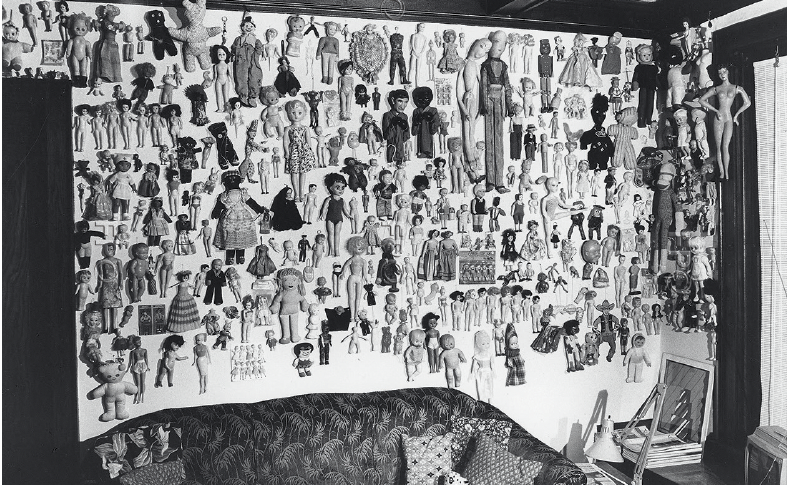

Ramberg was a prolific collector of objects that in turn served as potent sources of inspiration for her formal works. Frequenting thrift stores and garage sales, as well as the Maxwell Street Market by Chicago’s Southside, Ramberg sought what SAIC Professor Ray Yoshida dubbed “trash treasure,” a term used for one of the sections dedicated to her collecting within the retrospective.

An iteration of Christina Ramberg’s “Doll Wall” installed in her Chicago apartment (1972). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Of the myriad things she collected—from comic book pages to medical illustrations—Ramberg’s collection of dolls, which numbers into the hundreds, stands out the most. In several of the apartments Ramberg lived in throughout her life, she mounted many of these dolls on the wall as well as in exhibitions of her work, but never in the same arrangement twice. In the Art Institute’s retrospective, 155 of her dolls are on view in a manner similar to how she would have presented them. The collection of dolls speaks to her fascination with the body, and her collection ranged from relatively new, mass-produced pieces that reflected racial and gender stereotypes of the time to unique, handmade dolls that give insight into both the doll’s maker and its intended recipient.

Installation view of “Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective” (2024). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Ramberg discussed her doll collection in a 1989 Chicago Tribune interview, saying, “I was interested only in the dolls that had been owned by someone. The ones where the face was worn off and redrawn in, or where something very strange had transpired. What I like about them is their sense of history. I’m interested in what is implied. And the simple fact that they had a life.”

A Turn to Textiles

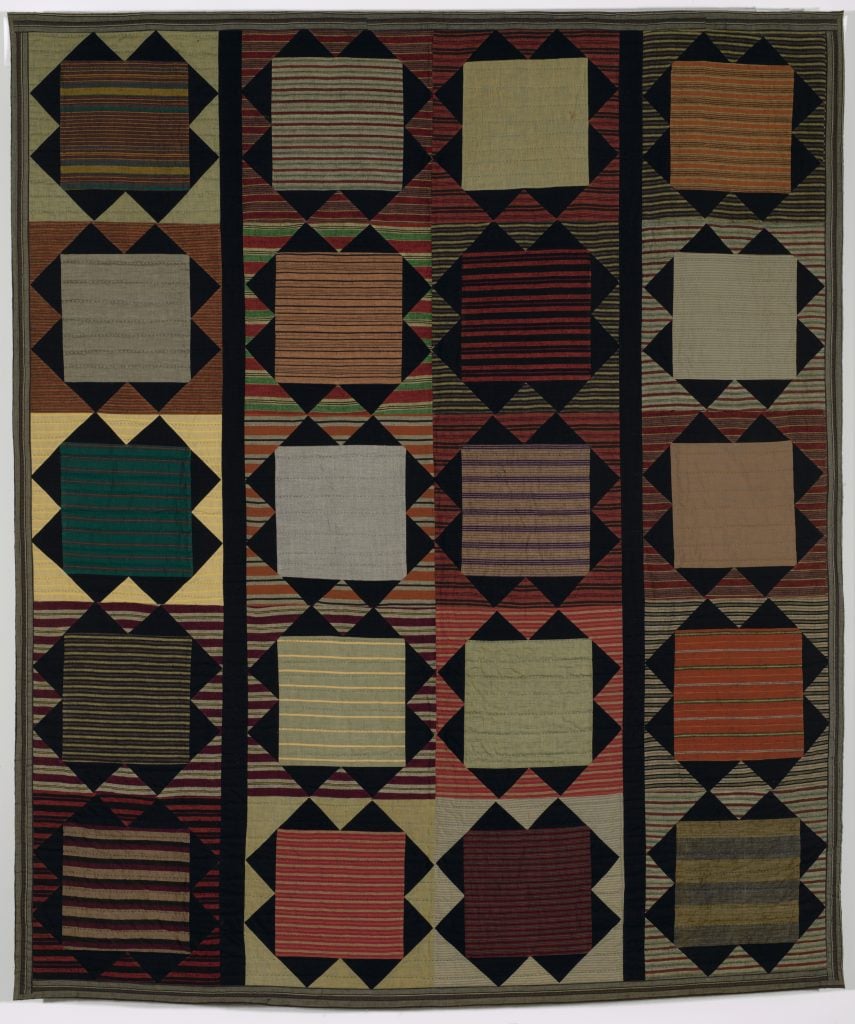

While Ramberg had long engaged with quilting as a pastime, it wasn’t until the early 1980s that it became a central aspect of her formal artistic practice, allowing her to step back from painting for several years. Beginning in 1983, her quilts were exhibited in gallery and museum shows, with each highlighting the experimental, explorative nature of her work—and harkening back to her penchant for collecting. Though Ramberg relied on traditional quilting techniques and construction, she frequently employed unusual color schemes and patterns as well as fabrics, which were sourced on her travels as well as “trash treasure” missions.

Christina Ramberg, Japanese Showcase (1984). Photo: Jamie Stukenberg. © The Estate of Christina Ramberg. Courtesy of the Estate of Ray Yoshida and Corbett vs. Dempsey.

Just as her habit of collecting provided creative inspiration, her time spent focused on quilting ultimately fostered new ideas and approaches to painting, which she returned to in the mid-1980s with her “satellite paintings.” These new works were markedly different from her previous paintings in both style and material; where previously she favored acrylic on Masonite and applied delicate layers of paint and used careful brushstrokes, she now worked entirely in oil on canvas with impasto paint application, intense scumbling, and visible underpainting.

Christina Ramberg, Untitled #123 (1986). Photo: Jamie Stukenberg. © The Estate of Christina Ramberg. Courtesy of Corbett vs. Dempsey.

Ramberg’s compositions too were a departure from her usual subject matter. The sketch-like geometry and lines, surely inspired by the grids and repetition of quilt patterns, are evocative of a satellite or transmission tower, and their inscrutability evokes the air of abstraction.

Installation view of “Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective” (2024). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Despite a return to painting, Ramberg never ceased quilting. The year before her diagnosis with Prick’s disease—also known as frontotemporal dementia, a rare neurodegenerative disease, which would take her life at the age of 49—she created some of the most innovative and dynamic quilts of her career. Synthesizing material from her archive of collected materials and compositional elements from her earlier paintings, she numbered these late quilted works starting with the Roman numeral “I,” as opposed to her other works of the period which were already numbered into the hundreds, indicating she saw these pieces as a fresh start and new horizon even at the twilight of her life.