Art World

In Zurich, Christo Traces the Arc of His Career, From Empty Storefronts to Mighty Ziggurats

The exhibition includes the only remaining works related to the failed wrapping of MoMA in 1968.

The exhibition includes the only remaining works related to the failed wrapping of MoMA in 1968.

Brian Boucher

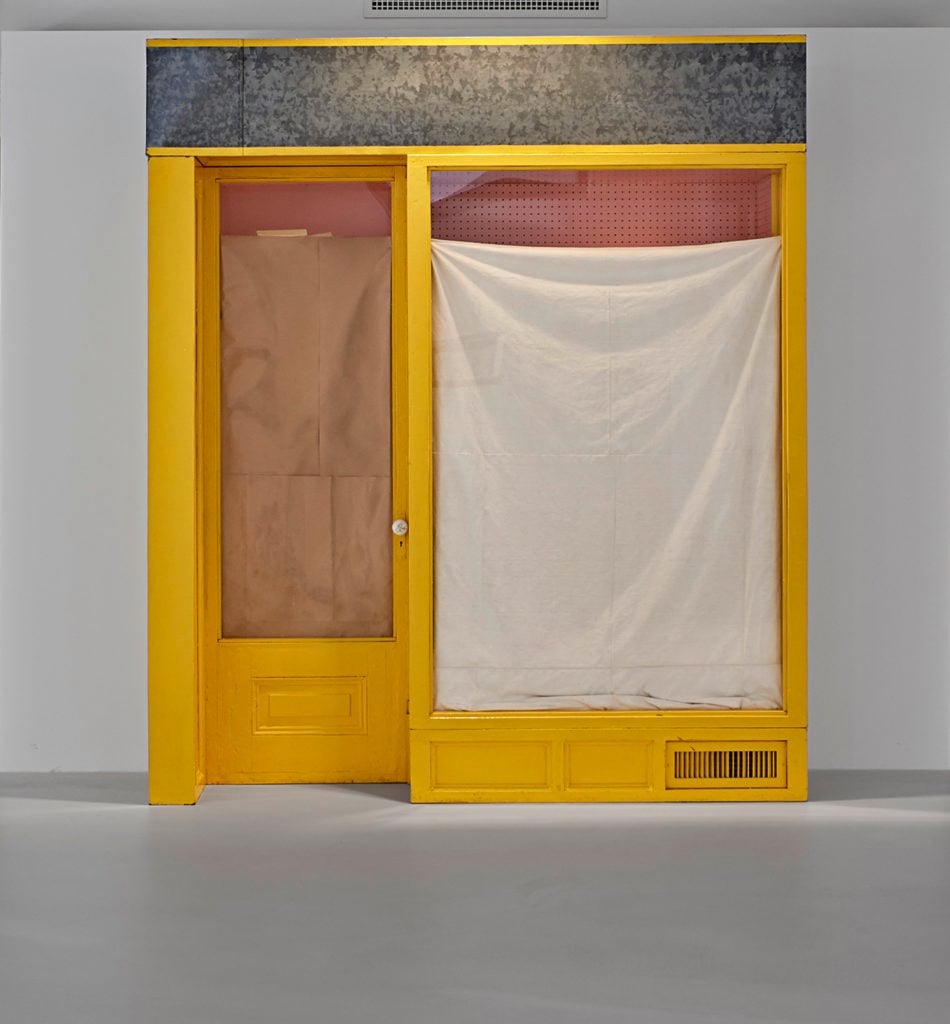

Christo was standing at Galerie Gmurzynska, in Zurich, one day last week, talking to reporters as news cameras snapped and as photographers frantically waved other visitors out of their shot. He was talking to this reporter about Four Store Fronts Corner (Parts IV, III, II and I) (1964-65), a full-scale sculpture of a storefront that he showed at Leo Castelli Gallery, at 4 East 77th Street. Just minutes before the show was to open, the artist was making a suggestion about how to improve the display of the work.

Christo’s Four Store Fronts Corner, 1964-65 (Parts IV, III, II and I), (1964–1965). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

On a pedestal nearby stands a scale model of the work, complete with a wood base that shows the size of the room where it was first shown, which must have created a claustrophobic experience. I wondered aloud whether there might be some way to indicate the small scale of Castelli’s gallery, relative to Gmurzynska’s big, sunny space.

Christo had an idea. “Perhaps you could suggest,” the artist relayed to a gallery staffer, “that you put down some tape to show the size of the gallery!”

Christo’s Le Jet d’Eau, Project for Geneva (1974). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

The Bulgarian-born artist is known worldwide for projects like The Gates, Central Park, New York City (1979–2005), in which he inserted thousands of orange gates into New York’s famed park; Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, (2014–16), which created a magical skin atop a private lake in Italy; and for wrapping buildings, monuments and other objects in cloth, such as Wrapped Reichstag (1971–75). The floor-tape moment indicated the fanatical attention to detail that has allowed those gargantuan projects, all undertaken with his late wife, Jeanne-Claude, to succeed.

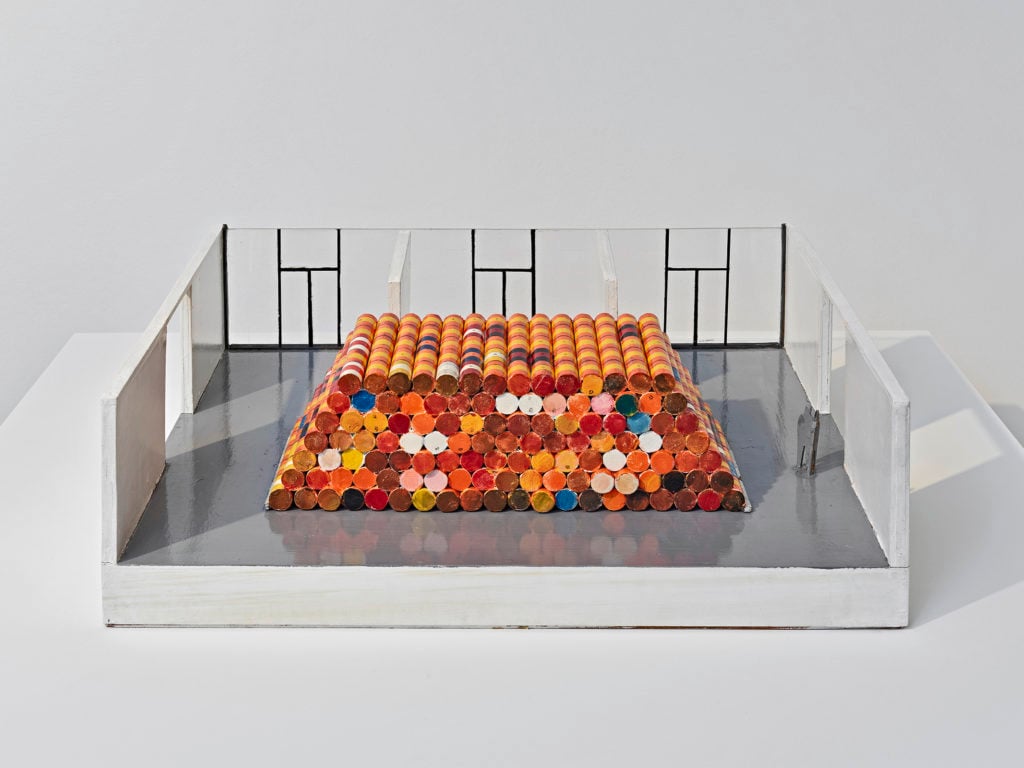

Christo’s Scale Model for Mastaba, Stacked Oil Barrels, Project for MoMA, NYC (1968). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

The exhibition on view through June 20 at both of Gmurzynska’s Zurich galleries includes some of the artist’s earliest works as well as studies for his forthcoming sculpture The Mastaba (Project for London, Hyde Park, Serpentine Lake) (2016–present). That work itself, consisting of 7,506 oil barrels floating on Serpentine Lake, could be viewed as but a study for The Mastaba (1977–present), a permanent work for the desert in Abu Dhabi, which will be among the world’s largest artworks.

Christo’s Yellow Store Front (1965). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

The storefront is a curious object, at just smaller than life size. Hanging beige fabric obscures the views into all its windows. Its steel exterior is accented by bands of red and blue along parts of the top and bottom; inside one window, a bit of faux-marble peeps out, while behind another curtain is some yellow pegboard, completing the triad of primary colors and suggesting a faint echo of Mondrian. The artist’s interest in architecture, he told the Architects Newspaper, grew out of his classical education at the Sofia Academy of Arts in his native Bulgaria, where students equally studied architecture and the fine and decorative arts.

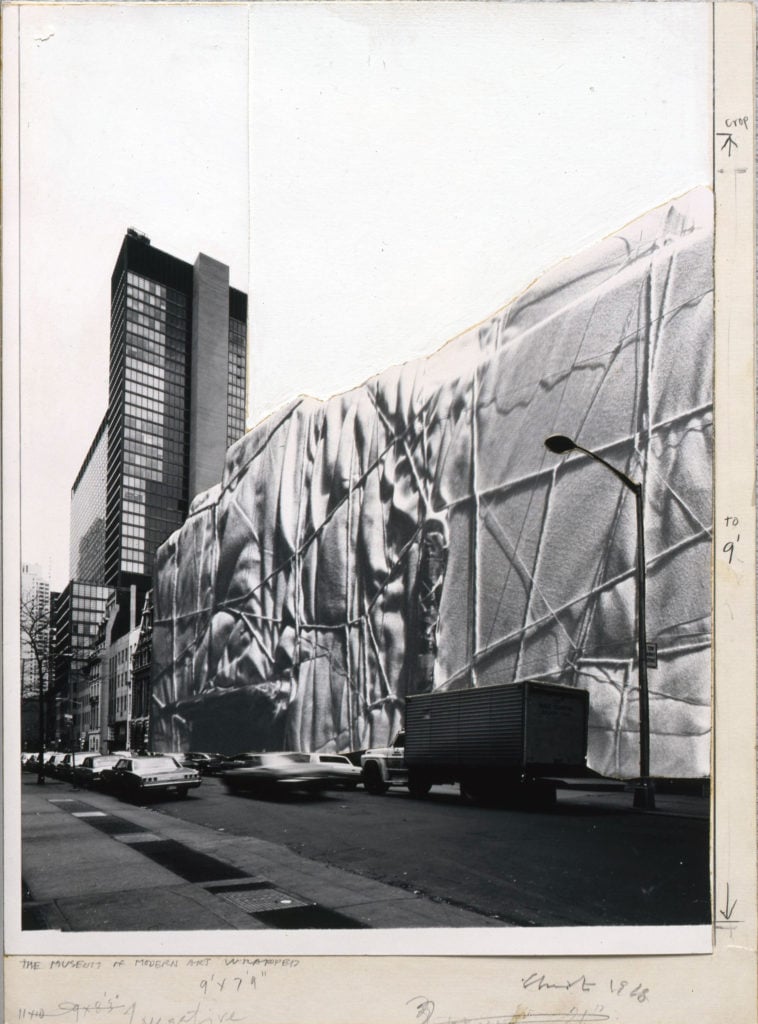

Christo’s The Museum of Modern Art, Wrapped (1968). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

Profoundly impressed with the New York cityscape on their arrival, Christo and Jeanne-Claude made a failed play to wrap two Lower Manhattan skyscrapers, 2 Broadway and 20 Exchange Place. Thwarted in their wish to go big and outdoors, they ironically went small, indoors, at Castelli.

After its debut, Four Store Fronts Corner went unseen until 2001, when it appeared in a show at Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau; it then was shown in 2016 at Art Basel’s Unlimited sector. It has meanwhile waited patiently at the artist’s storage space in Basel. He is fond of pointing out that he holds the largest collection of his own work, at what must be a sprawling facility. “More than any museum or collector!”, he said in Zurich.

The storefront work echoes Claes Oldenburg’s two first major bodies of work, The Street (1960) and The Store (1961–64), but obviously with the surreal twist of subjecting a mode of display to an act of concealment.

Interestingly enough, the artist allowed the door to open one time, in a 1967 show at Philadelphia’s Young Men’s/Young Women’s Hebrew Association. “The Museum of Merchandise” featured Pop and Op art as well as artist-designed furniture and fashions, which visitors entered through the storefront. “They should never be opened,” Christo told the New York Times back in 2003. “The door to ‘The Museum of Merchandise’ ‘Store Front’ was the only exception I ever made.”

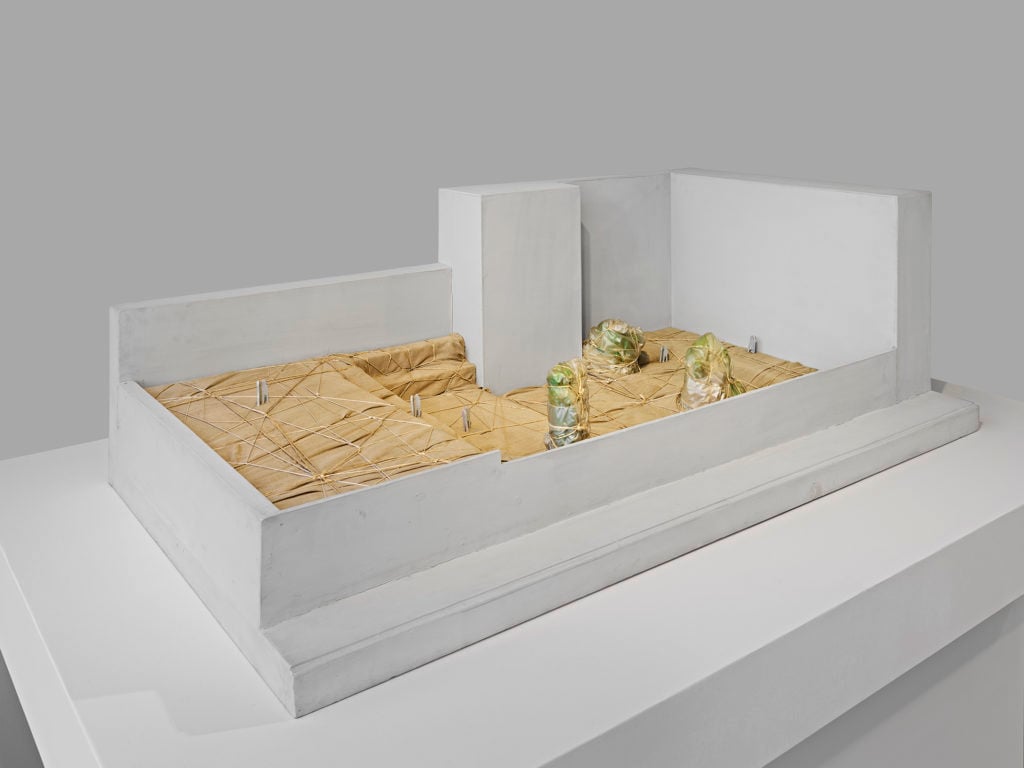

Christo’s Scale Model for Wrapped Trees and Sculpture Garden, Project for MoMA, NYC (1968). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

The Store Front projects, Christo points out, hold an important place in his trajectory. They marked a transition from the earlier small wrapped objects to his massive outdoor projects, such as his Valley Curtain, installed in 1972, and Running Fence, which Christo and Jeanne-Claude began work on in 1972, and which similarly used cloth to create divisions in space.

The current Zurich show also includes several gorgeous storefront sculptures and one smaller work, a single window with a beige cloth behind it, that echoes Robert Rauschenberg’s Bed, created just a few years before.

Christo’s Wrapped Trees Project for the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, 1968 (1968). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

At the gallery’s other Zurich showroom, designed by the late Zaha Hadid and featuring her trademark curvaceous sculptural design, are several collages and models relating to projects in Geneva, where the artist duo briefly during their passage through Europe to New York, where Castelli lured them with a promise of inclusion in a group show. But the exhibition’s principal offering besides the storefront is a set of works from a failed project in what would become their adopted home.

Christo’s Scale Model for Wall of Oil Barrels on West 53rd Street, Project for MoMA, NYC (1967–1968). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

In 1964, Museum of Modern Art curator William Rubin invited the pair to wrap the famed New York museum while it was vacant after his landmark show “Dada, Surrealism, and Their Heritage.” The artists also proposed blocking off the street with a wall of oil barrels as a riposte to the Berlin Wall, erected three years before. The museum now owns a collage and the sole model of the façade from the project, which was abandoned due to insurance liability. The Gmurzynska show includes the remaining models and collages for that project. The works all went on view at the museum in June 1968 in a show called, tongue-in-cheek, “Christo Wraps the Museum: Scale Models, Photomontages and Drawings for a Non-Event.” Now, 50 years later, the bulk of them are reunited.

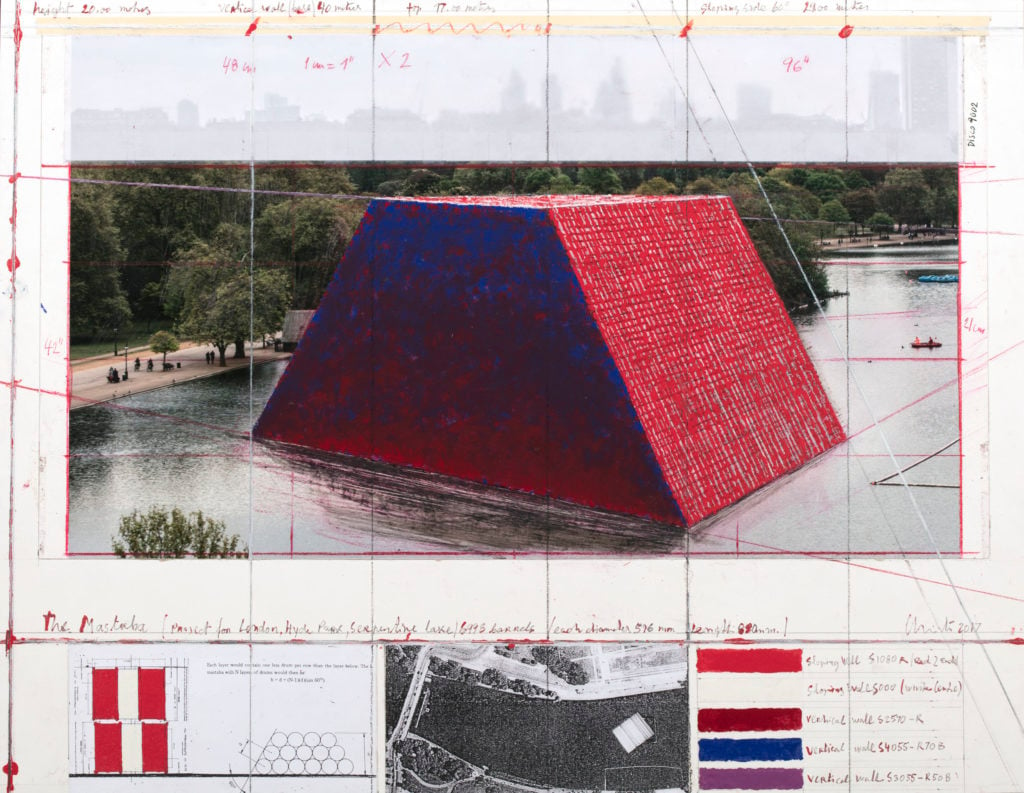

Finally, the show includes a collage picturing the London Mastaba in the Serpentine Lake, slathered in vivid reds and blues. That work will be on view starting June 18—a day after the close of the Art Basel fair—through September 23. Galerie Gmurzynska’s Mathias Rastorfer, studying the collage, pointed out a tiny paddleboat on the lake, noting that the man who rents the paddleboats is licking his lips in anticipation of a huge growth in business this summer. That piece will be just one-fiftieth the size of the one planned for the desert in Abu Dhabi.

Prices range from about $200,000 to the millions; as usual, whatever money goes to Christo is invested back into his own projects, so any buyers of these works may have the satisfaction of knowing that their money will go to support the gargantuan mastaba in the works in the desert of Abu Dhabi, which Christo told Interview Magazine will cost about $350 million.

Christo’s The Mastaba (Project for London, Hyde Park, Serpentine Lake) (2017). © Christo, courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

As for the duo’s auction market, their prices, recorded in the artnet Price Database, are low in view of their titanic status. Their top price is just under $600,000, paid for Wrapped Object (1961), at Christie’s Paris in 2014. Notably, four of their top dozen prices have been for works related to Store Fronts, or for a Show Window.

Christo is an apparently extremely fit 82, but his nephew, Vladimir Javachev, will finish the Abu Dhabi project if the artist doesn’t live to see it. Echoing the pyramids of Egypt, which serve as monuments to the kings of the ancient world, the Brobdingnagian work may stand for all time as a monument to an artist duo, who themselves have become art world royalty. Unlike most of his projects, it will stand permanently in the desert of Al Gharbia, near Abu Dhabi. Its 410,000 barrels will stand nearly 500 feet high, almost 1,000 feet wide, and more than 700 feet deep, so large that the footprint of St. Peter’s, in Rome, could fit inside it.

The project has been in progress since 1977, and he hopes very much to see it completed. Regarding its progress, he said, “It’s moving very fast.”

“Christo” is on view at Galerie Gmurzynska, Paradeplatz 2 and Talstrasse 37, Zurich, through June 20, 2018.