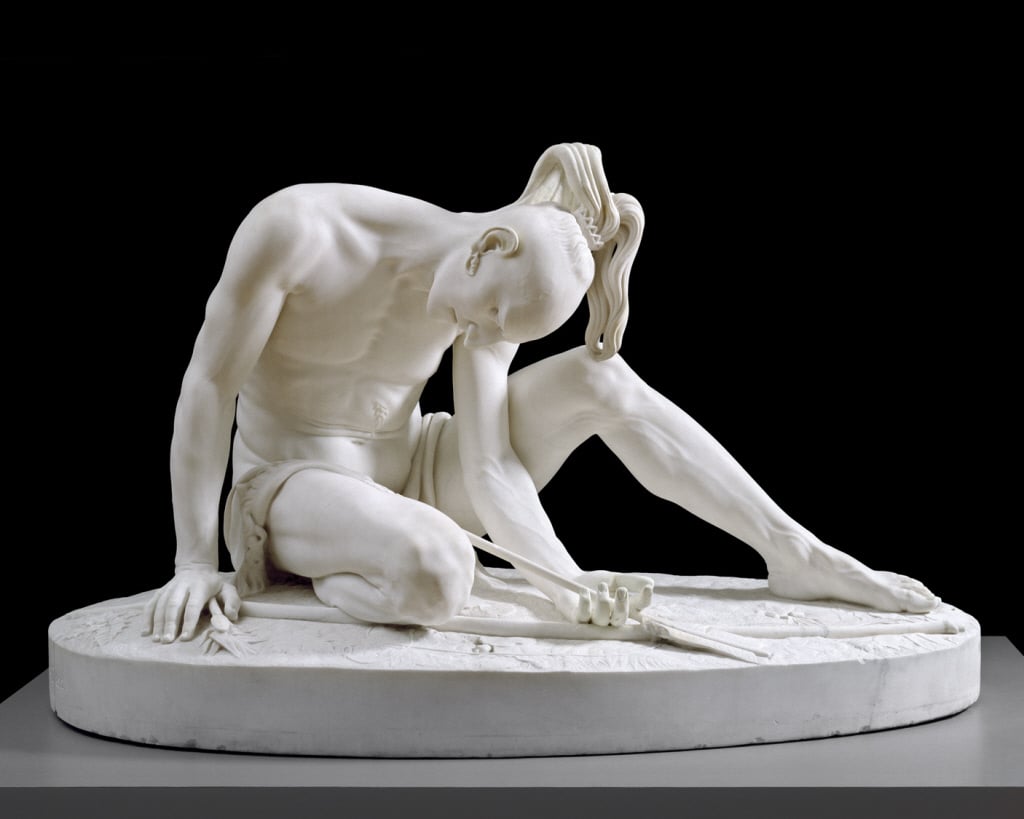

After 65 years, an acclaimed marble sculpture by Peter Stephenson is headed back to a Boston organization founded by Revolutionary War hero Paul Revere. The Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association (MCMA) secured the return of 1850 neoclassical masterpiece The Wounded Indian from the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, ending a nearly 25-year dispute over the work’s rightful ownership.

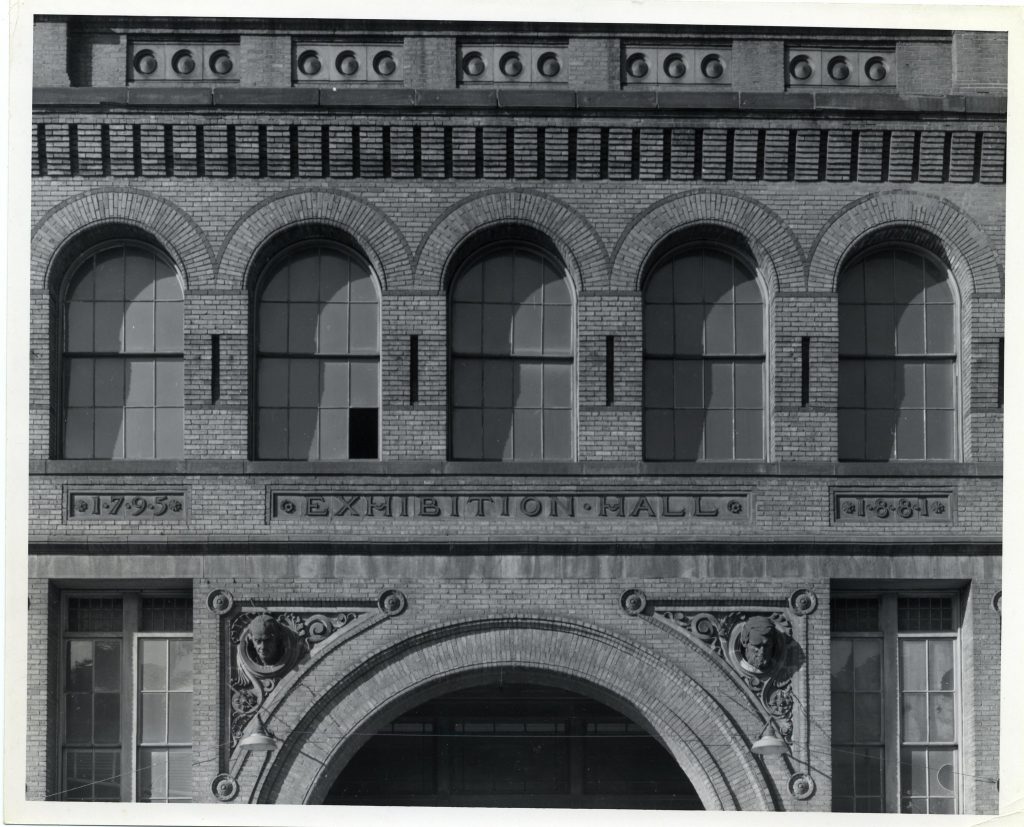

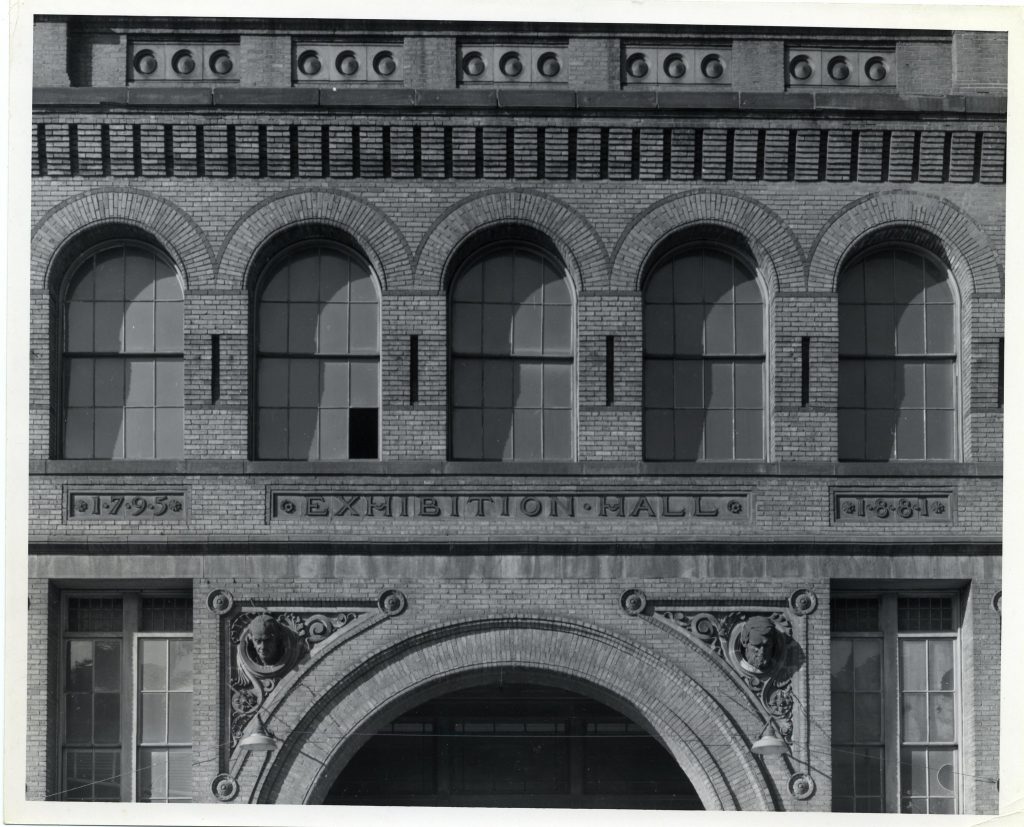

The MCMA, which Revere founded in 1795 to provide vocational training in the mechanical arts, acquired the sculpture via a donation in 1893, and put it on display in its Boston headquarters. There it remained until 1958, when financial difficulties prompted the organization to sell its 300,000-square-foot building, which was demolished the following year. (The site is now home to the Prudential Center.)

“During the chaos of moving, MCMA officials were told that the Indian had been destroyed,” Greg Werkheiser, a lawyer for the association, told the New York Times.

But the work unexpectedly turned up in 1986, when museum founder Walter P. Chrysler Jr. (Walter Sr. was founder of the Chrysler Corporation) bought it from an art collector named James H. Ricau. The MCMA discovered the sculpture’s whereabouts in 1999—after a visitor to their offices saw a photo of the lost work and recognized it from a trip to the Virginia museum—and has sought its return ever since.

The Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association Exhibition Hall in Boston, demolished in 1959. Photo Boston Landmarks Commission image collection, City of Boston Archives, Boston, courtesy of the Boston Landmarks Commission, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

The MCMA is not primarily a collecting institution, but has over time acquired a wide variety of cultural objects, including paintings by Jane Stuart, a piece of Benjamin Franklin’s equipment for electrical experiments, and the first pocket watch made with interchangeable parts. Since selling its headquarters, the organization has kept those works in storage, or loaned them out to institutions including the Smithsonian.

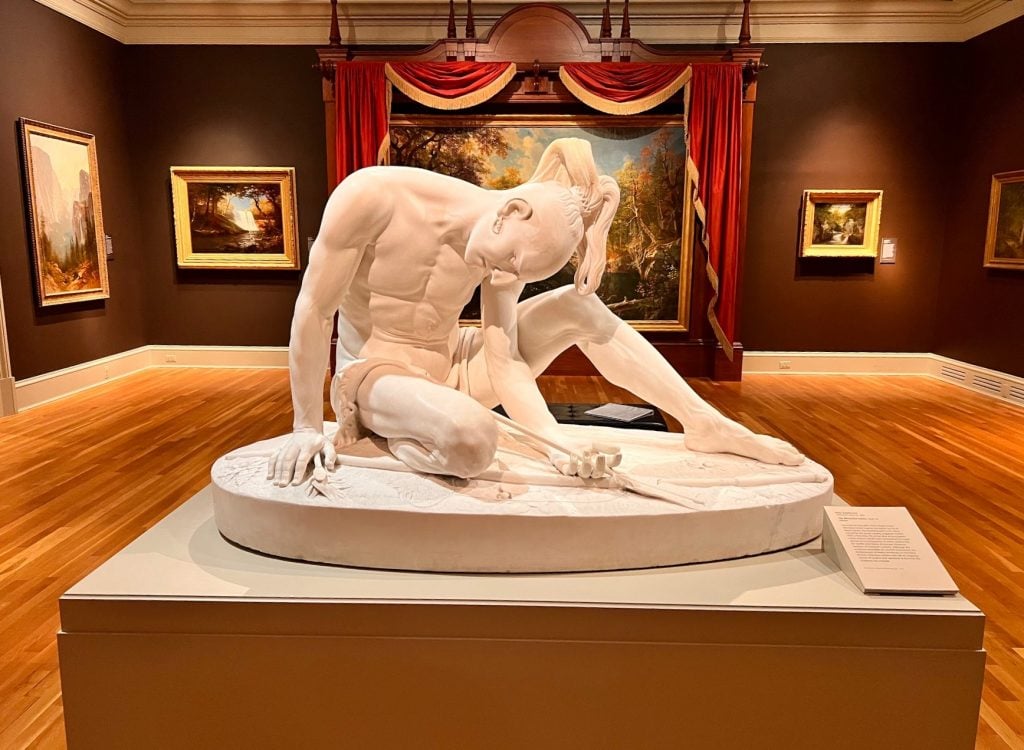

The Wounded Indian, thought to be the first life-size sculpture carved from a single block of American marble, which was quarried in Vermont, was one of the gems of the Chrysler collection, prominently displayed in the museum’s American galleries in front of a massive Albert Bierstadt Hudson River School landscape draped in velvet curtains and other large-scale marbles and paintings.

The sculpture was part of a now-controversial tradition of 19th-century American artworks romanticizing the perceived extinction of the Native American people. U.S. settlers killed the Indigenous population in large numbers, both through violence and by introducing deadly diseases, and forced tribes to leave their homelands and move west of the Mississippi.

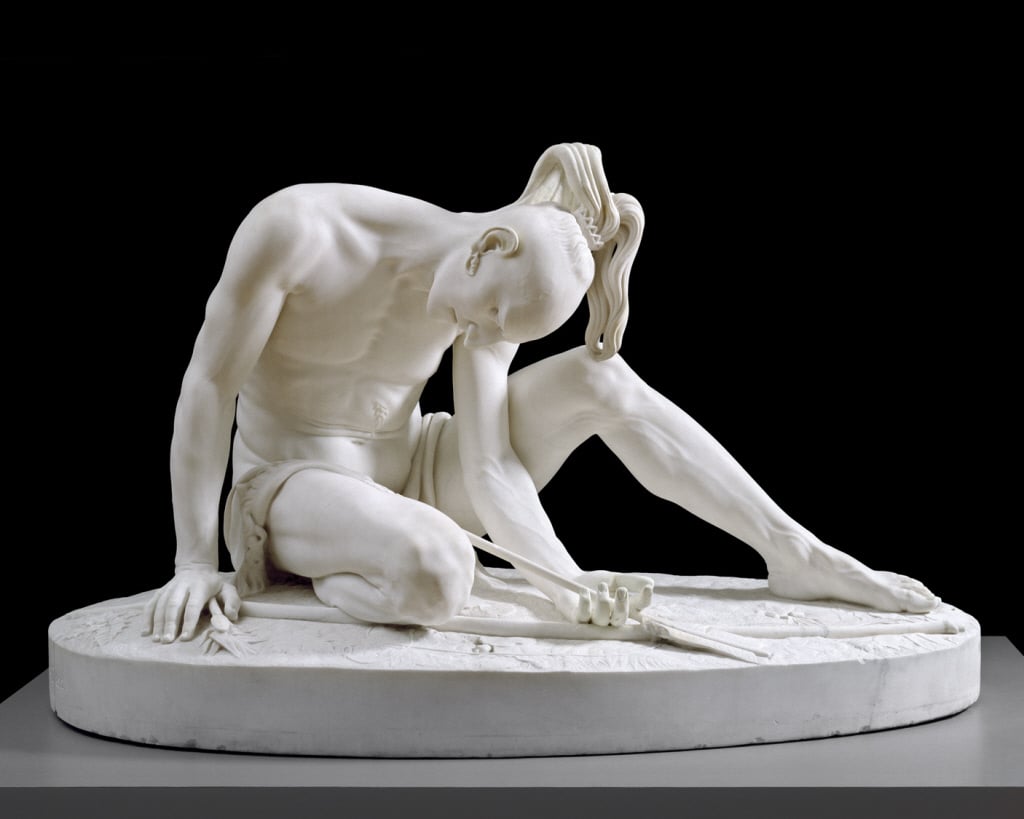

Stephenson drew inspiration for the piece from the famous statue The Dying Gaul, part of the collection of the Capitoline Museum in Rome and itself an ancient Roman copy of a Greek original. The sculpture made its debut at London’s Crystal Palace during the Great Exhibition of 1851, but Stephenson’s career was cut short by mental illness, and he died at age 37 in 1861.

The Dying Gaul (ca. 1st or 2nd century, C.E.). Courtesy of the Sovrintendenza Capitolina, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy.

When first confronted, the museum suggested that the MCMA must have owned a copy of the original piece. However, the Virginia institution was well aware that the work’s provenance had always had gaps. Ricau had said he bought it from Boston’s Vose Galleries, but the business told the museum in the early 1990s that it had no records of having sold the work.

On the other hand, the sculpture had arrived at the Chrysler with considerable damage, missing all the figure’s fingers on the left hand, part of his hair, and an arrow shaft. The museum argued the MCMA simply had abandoned the damaged sculpture when it no longer had a place to house it, and had come to regret that decision. (The MCMA categorically rejected that charge, saying that “no rational person or reputable organization, especially one that had meticulously maintained such a cherished piece of art for 65 years at the center of its collection, would discard The Wounded Indian due to such minor damage.”)

The MCMA hired a law firm specializing in art ownership, Cultural Heritage Partners, in Washington, D.C. Eventually, the Chrysler agreed to enter into negotiations with Werkheiser and Paul Revere III, the MCMA’s general counsel and a fourth great-grandson of its silversmith founder.

In 2020, the two sides almost reached an agreement, which would have kept the work in Virginia in exchange for recognition of MCMA’s ownership, a six-month loan to Boston, and $200,000 to cover the association’s legal fees and research costs. But the city of Norfolk, which helps fund the museum, balked at what a deputy city attorney called a “frankly outrageous monetary demand.”

Peter Stephenson, The Wounded Indian (1850), detail. Photo by Stewart Gamage, courtesy of Cultural Heritage Partners.

In response, the MCMA withdrew its offer to arrange a loan that would have kept the piece at the Chrysler.

“Long-term collaborations require a foundation of trust, and regrettably, the leadership at the Chrysler has consistently proven unreliable,” the organization said in a statement. “Museum leaders falsely claimed that their sculpture was the original and ours had been a copy, leading MCMA on an exhausting and expensive journey to debunk this myth. Current Chrysler leaders withheld crucial documents for three years. These documents revealed—among other surprises—that Chrysler leaders had been aware for at least 32 years that the Chrysler lacked documentation of legal ownership of The Wounded Indian.”

With negotiations at an impasse, the MCMA took its claim to the press in May, and reached out to the FBI, claiming the artwork had been stolen in 1958.

“We just reached the point where we said ‘this is crazy. We want the damn thing back,’” Chuck Sulkala, president of the MCMA board, told the Washington Post in the first article detailing the dispute. “It’s that simple.”

Peter Stephenson, The Wounded Indian (1850). Photo courtesy of Google Arts and Culture.

The ensuing wave of media attention and the FBI’s launch of an investigation by its Art Crime Team made it clear “these ragtag guys up in Boston aren’t going away,” Sulkala told the Boston Globe. “We’re a small organization compared to the Chrysler, but we were dead serious that we wanted this back.”

Now, the two sides have now reached an agreement. The Chrysler will return the work without any additional payment, and the MCMA, which is currently without an exhibition gallery, is making plans to exhibit it at a Boston institution. (As part of the terms of its original acquisition, donor James W. Bartlett, a Boston collector, required that the association clean the work and put it on public view.)

“In the 24 years since we first stated our claim to the Chrysler, we have reminded ourselves often of our motto: ‘Be Just and Fear Not.’ It has paid off. The Wounded Indian is coming home,” Revere said in a statement.

The museum is “pleased with the amicable solution,” Chrysler director Erik H. Neil said in a statement provided to the Art Newspaper. (In June, the Chrysler repatriated a Bakor monolith to Nigeria, receiving in return a near-identical-looking facsimile from the nation’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments.)

“Ultimately, the leadership of Chrysler did the right thing not just for the MCMA and their own institution, but also for the art field as a whole,” Werkheiser told the Globe. “A visible return like this, after so many contentious years, will inspire other institutions that it’s rarely too late to correct a historic wrong.”

More Trending Stories:

The British Museum Has Reached a Settlement With a Translator Whose Work Was Used in an Exhibition Without Her Permission

Known as a Deep-Pocketed, ‘Aggressive’ Chinese Collector, Ding Yixiao Has Now Been Blacklisted by the Art Market. What Happened?

A German Court Rules That Martin Kippenberger’s Estate Must Name a Painter Who Executed His Works as a Co-Author

Can a Digital Artwork Outlast a 19th-Century Painting? The Answer Is Complicated as Artists, Dealers, and Conservators Battle Obsolescence in the Field

A Sculptor’s Lawsuit Against Kevin Costner Over Artwork She Created for His Planned Luxury Resort Will Finally Go to Trial

Creepily, the Woody Allen Romp ‘Vicky Cristina Barcelona’ Channels the Book That Outed Picasso’s Treatment of Women

JTT, the New York Gallery Known for Minting Star Artists, Is Closing After More Than a Decade

The British Library Has Discovered Scandalous Details Censored From the Official Account of Elizabeth I’s Reign