Art World

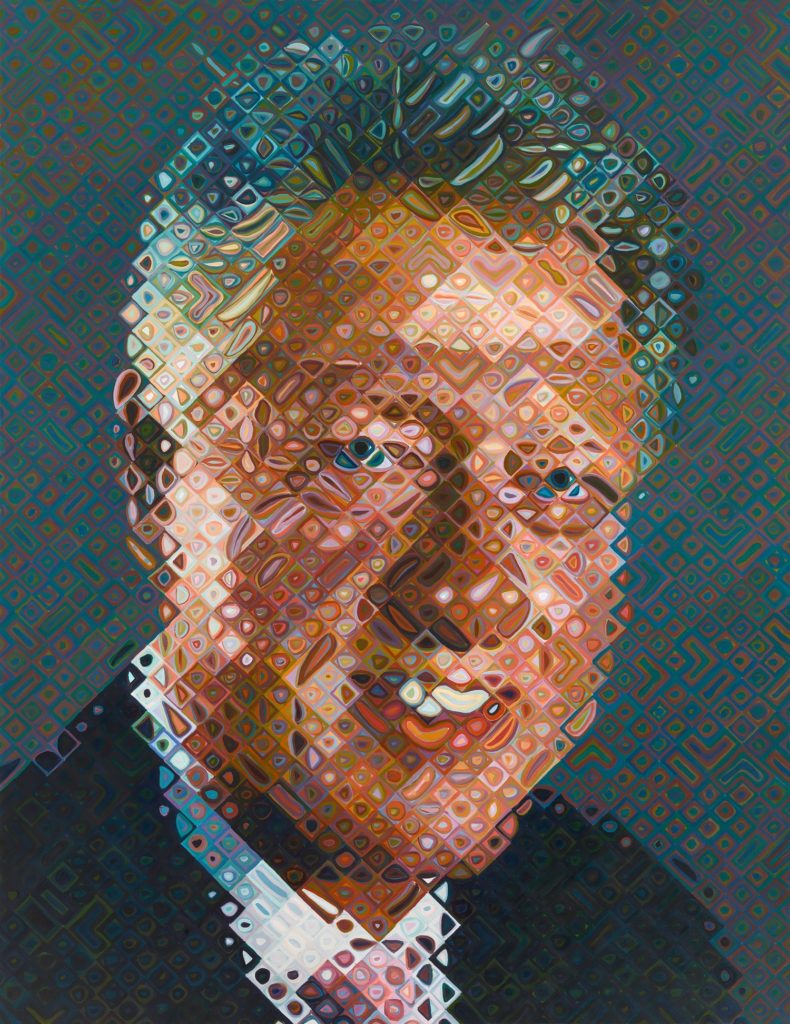

Chuck Close Was a Celebrated Art Star Until MeToo Exposed Him as Toxic. Can His Supporters Stage a Posthumous Comeback?

Close serves as a test case for how an artist who faced harassment allegations in life will be remembered in death.

Close serves as a test case for how an artist who faced harassment allegations in life will be remembered in death.

Zachary Small

Immediately following his death in August, the artist Chuck Close received the careful reconsideration reserved for troubled artistic geniuses.

“Will his paintings regain visibility?” asked New York Times critic Roberta Smith in an article weighing the painter’s legacy soon after he passed away from cardiopulmonary failure at 81. “Now it will be interesting to see when and how Close’s career is rehabilitated and whether it will garner an ‘asterisk,’ a label warning viewers of the less savory aspects of his life.”

You won’t find Close’s monumental portraits currently on view at prestigious institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His paintings are also absent from the upcoming auction season, a noteworthy omission in a market where prices typically spike after an artist’s death.

Close, who became famous in the 1970s for his distinctive, monumental paintings and self-portraits that toyed with viewers’ perceptions, has been largely out of the spotlight since 2017, when several women accused him of sexual harassment. He apologized for having made women feel uncomfortable but also disputed some of the allegations.

Fallout for the artist included canceled exhibitions, lost business opportunities, and a retreat from public life. It was a stressful moment for Close, who had received a diagnosis two years earlier of frontotemporal dementia, a disease that can alter one’s personality and lower inhibitions.

Despite these obstacles, gallery employees and former studio assistants tell Artnet News that he was planning a grand return in his final years—one that would have tested the longevity of the MeToo movement in the art world.

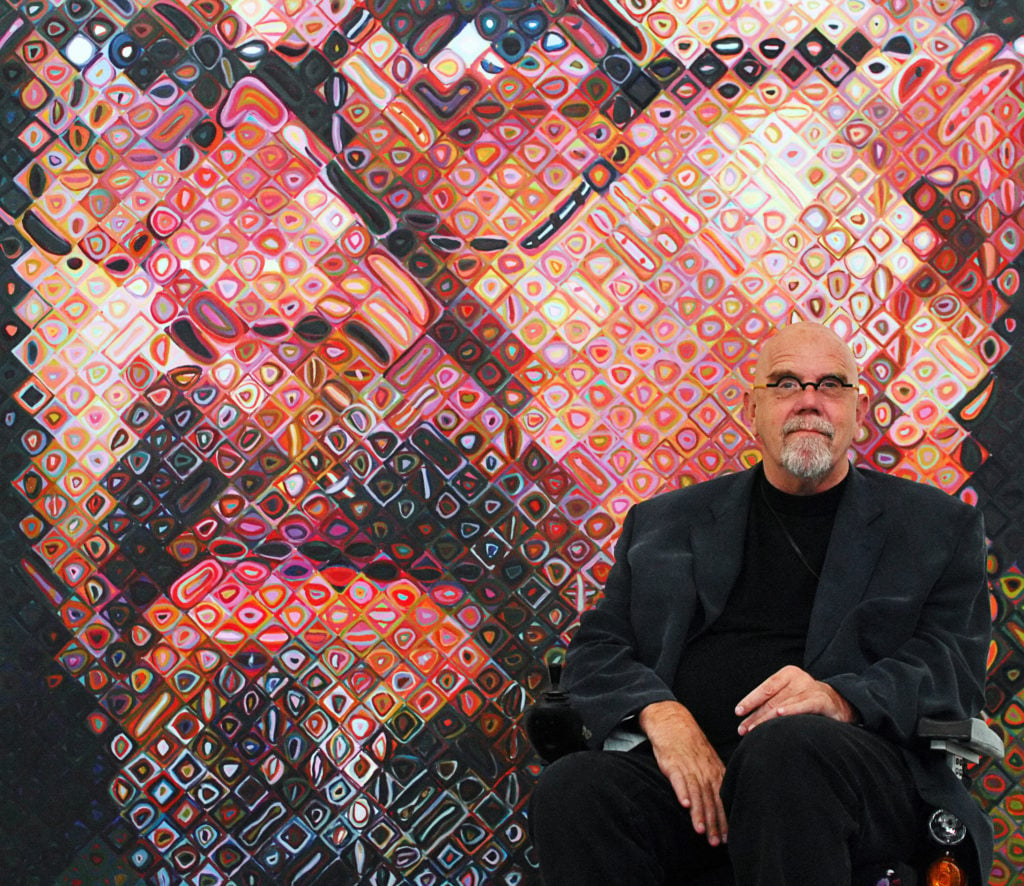

Chuck Close painting in his studio. Photo courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Where Close’s work ultimately lands in the canon of American art will serve as the art world’s first test case for how an artist who faced sexual harassment allegations in life will be remembered in death. The posthumous revelation of his medical diagnosis, which his family—now in charge of the artist’s estate—maintains was the sole reason for his behavior, only makes matters more complicated.

“We have to discuss how his sexual misconduct informs the elements of his work,” said Kelli Morgan, a professor at Tufts University who curated a 2017 exhibition of the artist at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and recalled administrators warning her to omit mention of harassment allegations. She left the museum shortly thereafter. “We need to start looking at this work through the lens of sexual abuse, which unfortunately not a lot of curators are trained to do.”

Other museum leaders would like to separate the creator from his creations. “You do need to make a differentiation between the artwork and the life of an artist,” said Max Hollein, the Met’s director, in a recent Artnet News interview when asked about the painter’s legacy. Close’s portrait of artist Lucas Samaras was on view at the museum until March of this year. “The idea that you can only look at an artist’s work where the life of the artist is impeccable seems absurd,” Hollein said.

Although the architecture for a planned comeback crumbled when Close died, the question remains if the “canceled” artist can stage a return from beyond the grave as museums reckon with the troubling aspects of his biography and new misconduct allegations emerge alongside accusations that a Pace Gallery executive was involved in efforts to silence victims of his abuse to protect the star artist.

Some market experts believe it’s only a matter of time until Close sees a resurgence in both the market and museums. After all, he was an established, blue-chip figure for decades before the 2017 revelations. “There is such an institutional consensus around him that he will remain part of the art-historical canon,” said Natasha Degen, art-market studies chair at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology.

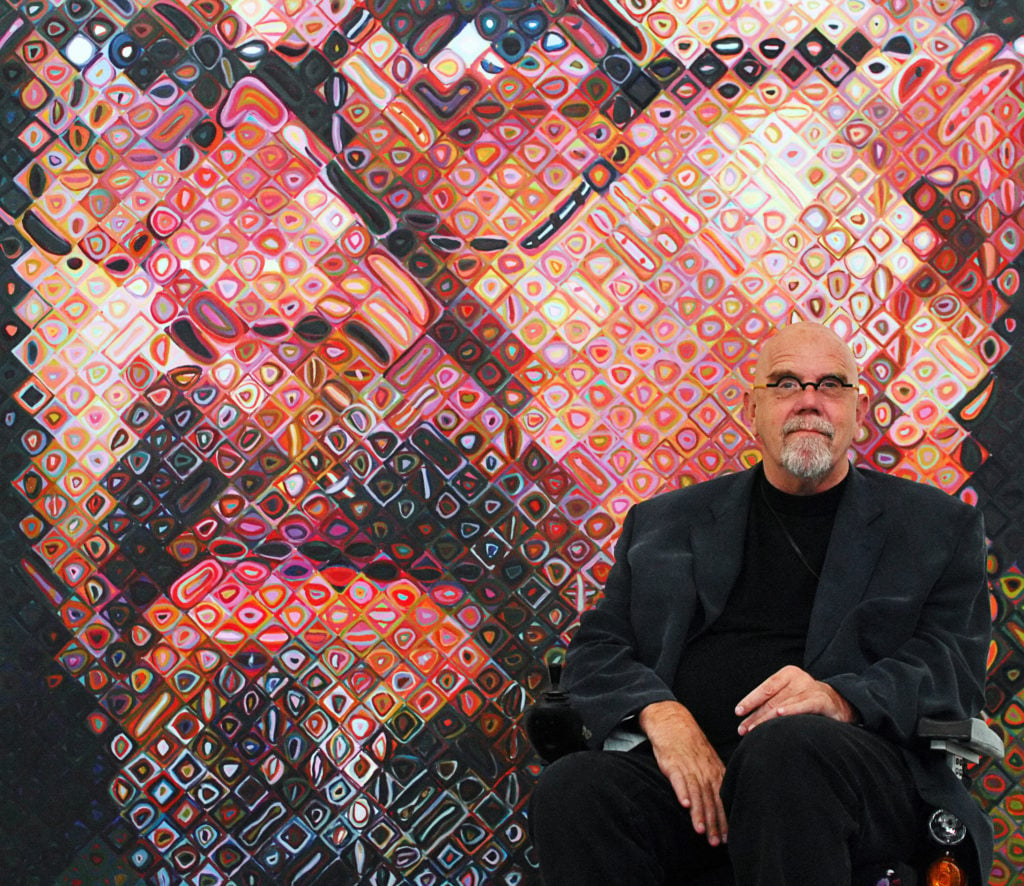

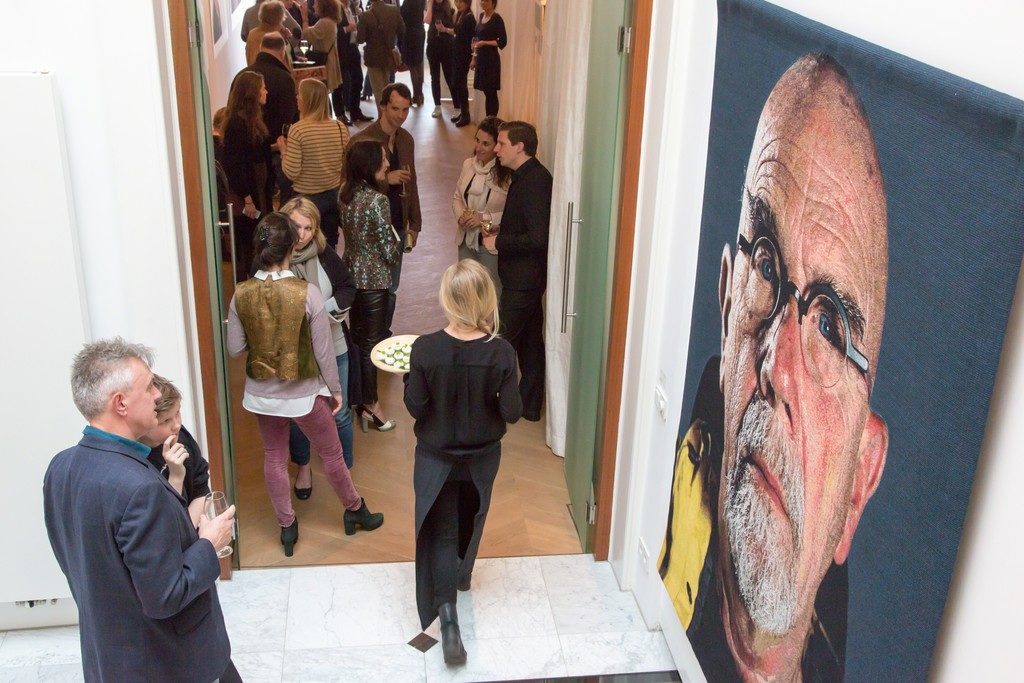

Installation view, “Chuck Close” at the Merchant House (2015). Courtesy of the Merchant House.

Close’s medical condition was not made public before his death—but neither were additional allegations about the way the artist ran his studio and the lengths he went to in order to maintain his reputation.

Around 2014, the studio environment was getting “toxic,” according to three former employees interviewed by Artnet News on the condition of anonymity because they had signed non-disclosure agreements. “It was difficult to tell when lines were crossed,” one former assistant said, “and if it was because of his disease or his desires.”

Close was first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in December 2013, and his neurologist has said he may have manifested symptoms several years prior. (His diagnosis was amended to frontotemporal dementia in June 2015.) The earliest known misconduct accusation against Close dates to 2001.

The artist became more erratic as his condition worsened, employees said. Sienna Shields, an artist and Close’s wife from 2013 to 2016, who often worked in his studio as a caretaker, said he brought escorts into the studio; nurses also reported that he sexually harassed them, according to four sources.

At least two employees with sexual misconduct complaints received financial settlements from Close in exchange for their silence, sources said. Shields said she also repeatedly asked Close to stop watching pornography during work hours after employees complained.

In 2015, Shields raised alarms about the artist’s behavior, mental state, and conduct with employees to Arne Glimcher, Pace’s founder and a longtime friend of Close, in emails reviewed by Artnet News. She believes her concerns were not adequately addressed. “I was the invisible black woman,” Shields wrote in one of the messages. “I still am.”

Glimcher ended up playing a mediating role in the couple’s divorce, helping to settle a dispute over a painting that Close had promised Shields in their prenuptial agreement. The artist had originally estimated that the work, a self-portrait, was worth somewhere between $3 million to $5 million. But during negotiations, Close damaged the painting and an appraisal organized by Glimcher through Mnuchin Gallery gave the artwork a lower estimate, at $1.35 million.

The two parties eventually found a resolution: Shields would forfeit her right to alimony and receive a property the couple shared in Alaska. Close would reclaim ownership of the painting and disburse $100,000 payments among a dozen former aides to make amends for hours of unpaid work tending to the artist.

“People really gave so much of themselves all the while being harassed and demeaned,” said Shields, explaining why she insisted on the payout and claiming that Close was verbally abusive and slandered her in the art world.

Close also leaned on lawyers to silence his critics. When Shields began posting on Instagram in 2018 about her experience with him, she received a cease and desist letter from the artist’s lawyer. (Shields noted that she never signed an NDA even though Close began to strictly enforce the practice in his studio in the wake of the 2017 misconduct allegations.)

“You have repeatedly and maliciously violated that solemn promise to respect Mr. Close’s privacy,” said the letter, reviewed by Artnet News. “Your actions have caused him massive injury, including the cancellation of a planned show in London, reputational damages, and the loss of potential sales.” In a statement to Artnet News, a Pace representative said that the gallery was not involved in sending the legal letters.

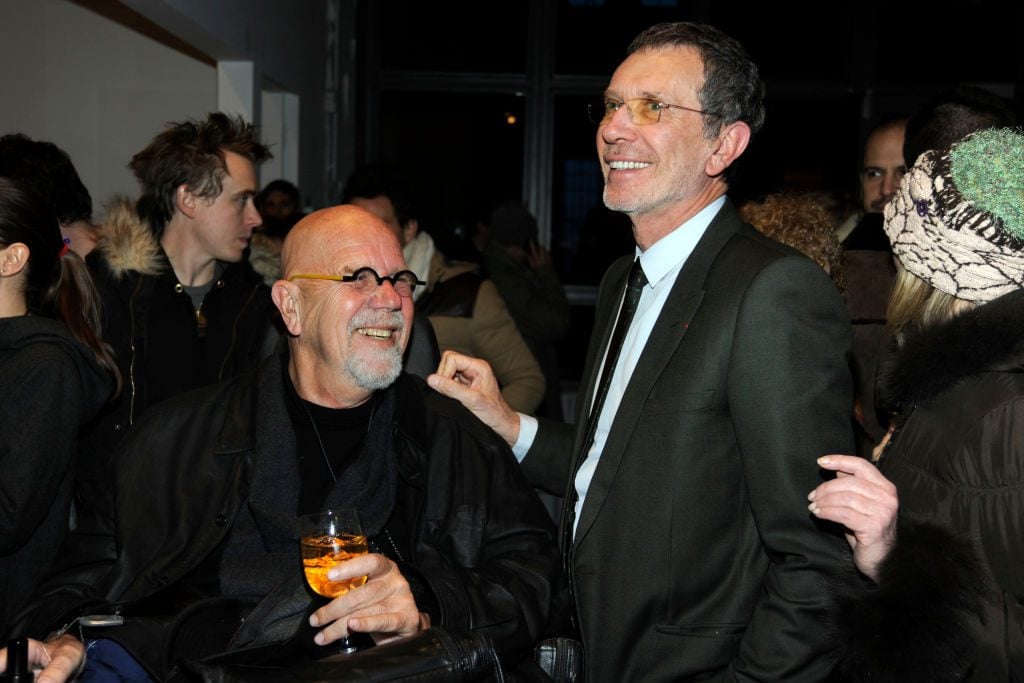

Chuck Close and Arne Glimcher attend a PaceWildenstein event at The Standard on February 4, 2009 in New York City. (Photo by JOE SCHILDHORN/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images)

The canceled exhibition that Close’s lawyer was referring to was likely the one scheduled for White Cube in London. But it wasn’t because of Shields that the show was scrapped. Two employees close to the matter said that the gallery decided to table it when several female gallery directors expressed concern about his record with women. Last year, the gallery opted to present the painter’s work at its Hong Kong outpost in collaboration with Pace. (White Cube did not respond to a request for comment.)

The show points to broader questions about how galleries sought, and will continue to seek, to burnish Close’s legacy. When the sexual misconduct allegations against Close first became public, veteran Pace executive Douglas Baxter dismissed the allegations in a call with Terrie Sultan, then the director of the Parrish Art Museum, saying of one of Close’s accusers, “Maybe this young woman should go live in Puerto Rico and be a hurricane victim, or starve in Haiti or Ethiopia, or be a bomb victim in Aleppo.”

Arne Glimcher did not respond to accounts about his role in the couple’s divorce or whether he had prior knowledge of Close’s misconduct. Asked about Pace’s approach to Close’s career, a gallery spokesperson said: “The role of a gallery is to promote the work of artists they believe in. This includes preserving artists’ legacies by ensuring that their work has a lasting presence and that their contribution to art history is understood. Pace will continue to create opportunities for audiences to experience Close’s work, in concert with the estate and according to their wishes, including the organizing of future exhibitions at our galleries worldwide, supporting museums in the coordination of exhibitions, and generating conversation and new scholarship on Close’s work through publishing and digital projects.”

Last year, gallery executives were preparing a grand comeback for the artist: a New York exhibition that was to be overseen by Pace president Susan Dunne. Plans were at an advanced stage in November, according to two employees close to the project, but were put on an indefinite pause when Pace announced its investigation into the workplace conduct of Dunne and her colleague, Baxter, following an Artnet News report about the gallery’s work environment.

(Dunne resigned from her position and later joined David Zwirner as a senior director. Baxter also stepped down, but remains a senior advisor to Pace.)

Chuck Close, William J. Clinton (2006). Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

So far, Pace has had middling success in advocating for Close in the wake of the controversy. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., canceled his 2018 exhibition because of the allegations surrounding him. His only shows since have been the joint outing at Pace and White Cube in Hong Kong in 2020 and a Gary Tatintsian Gallery show, co-organized with Pace, in Moscow earlier this fall.

According to Pace, the majority of the works from the Tatintsian show sold. But following Close’s death, his art has not been available for sale and will remain off the market while the estate is in probate.

Meanwhile, Close’s auction market has flatlined. In 2015, a monumental grisaille self-portrait from 2007, painted in the artist’s pixelated style, fetched $2.4 million at auction; in 2020, a similarly scaled portrait from the same year of the artist’s first wife Leslie Rose fetched $615,000.

“With the auction houses mostly dealing in editions and prints for the artist, bigger works are likely being sold privately to avoid attention,” said Lisa Schiff, an art advisor.

Close’s auction sales peaked in 2005 when a number of his most important paintings hit the block; his work generated $8.5 million that year. Since 2017, according to the Artnet Price Database, his results have hovered between $572,000 and $672,000 annually (with the exception of 2020, when the sale of Leslie buoyed his total to $1.3 million).

According to Pace, Close’s auction market has remained consistent over the years. “Close’s work has never been hugely present at auction,” the Pace spokesperson said. “The notion of a windfall of auction sales immediately following an artist’s death tends to be a misconception.”

The museum world, meanwhile, appears to be keeping its distance from Close as questions around his legacy remain unresolved. Behind the curtain, efforts from powerful entities like Pace can do much to shape the way an artist is remembered.

“I hesitate to publicly criticize him,” said the art historian Robert Storr, referring to Close in a 2018 conversation with Shields. (He did not respond to a request for comment on this article.)

In 1998, Storr curated the MoMA retrospective that cemented the artist’s place in history. Nearly a decade later, he was the Yale School of Art’s dean when a student said she was sexually harassed by Close. When the allegations became public in 2017, he stopped short of condemning the artist.

“I don’t think he can be reformed and I don’t think Arne [Glimcher] can be reformed and I don’t think the system in SoHo, Tribeca, or the Westside Highway can be reformed,” he told Shields in a recording reviewed by Artnet News. “That system is locked into its ways. It’s about money.”