There is a particular thrill in meeting Cindy Sherman over FaceTime. Here is the face that has been the blank canvas for hundreds of characters over the decades, now under a radiant late September glare. The artist “meets” me from her Hamptons home, fresh from opening a survey at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and an exhibition of new photographs at Metro Pictures in New York this past week.

To have a virtual rendezvous with the artist who has continuously deconstructed and rebuilt identities is to come face to face with the emblematic expression that has delivered both the most gruesome and delectable ranges of human emotion and pierced our perceptions of truth—a concept that social media has shifted dramatically in recent years.

Every time I plunge into a rabbithole of Instagram grids or pose for an intricately-angled selfie, I ask myself, “What would Cindy Sherman think?”

“I actually don’t think about the current image excess much,” says Sherman, the artist arguably behind the first true selfie of modern times. Sherman’s own Instagram account mainly displays to 323,000 followers grotesquely manipulated selfies, peppered between beach snaps and celebrity-studded galas. “I really got into Instagram when I started experimenting with these selfie filters,” she says.

The reason she’s been scrolling up and down lately, however, is to get her hands on new techniques. Drag queen accounts like that of Kim Chi from the eighth season of RuPaul’s Drag Race have been a source of inspiration for make-up tricks. “I love this technique of covering eyebrows with Elmer’s glue,” Sherman says. But her fascination with gender play exceeds contour tricks. Drag is one of the territories she has thought about exploring in her long career of “becoming.” Like clowns, which she explored with a series in the early 2000s, Sherman thinks “drag queens are fascinating for creating trademark characters through configuration of make-up, costume, and, most importantly, identity.”

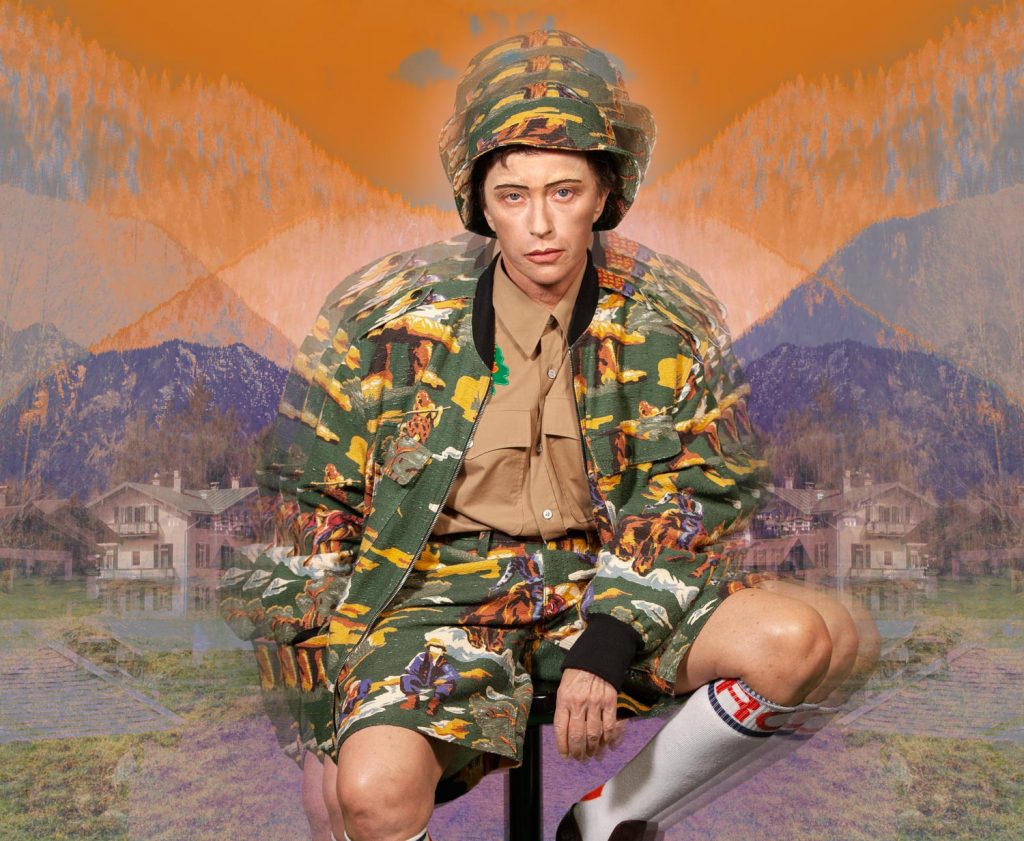

While Sherman has experimented with male characters before, such as in her “Doctor and Nurse” and “History Portrait” series, she has never shown an entire group of male characters like she does in her new show at Metro Pictures. The exhibition features 10 photographs of the artist posing as men, occasionally escorted by a female counterpart, and each wearing accentuated attires in front of landscapes the artist photographed during her recent travels. Donning items from fashion designer Stella McCartney’s menswear collections, Sherman’s male figures are subtly performative, but not over the top; sufficiently masculine, yet notably idle.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #613 (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

For an artist who has unabashedly transformed herself into multiple varieties of womanhood throughout her career, Sherman admits to feeling challenged by male representations. While experimenting with becoming men in the past, she says her “preconceived idea for how men act” never yielded the desired result. “They appeared generic and unsympathetic,” she says, recalling how she tried to fit into men’s roles while shooting her famous “Untitled Film Stills” series of 1977-80. That she’s returned to male subjects during recent discussions around toxic masculinity, particularly since the beginning of the #MeToo movement, is a total coincidence, she says, and one that even made the artist question her decision to hit the shutter. “I wondered if the idea could be read as too ‘of the times,’” she adds. The process eventually involved some learning, from pinning her hair down for a receded hair effect to posing with the right dose of imaged testosterone.

Photographs may be the embodiment of Sherman’s oeuvre, but performance has been its backbone, and, in this regard, female characters have proved especially helpful. “They always have stories and emotions visible on the surface,” she says, referring to her “larger-than-life fabulous ladies.” For male characters, Sherman had to concoct a different performativity, in which ordinariness would become the signifier of gender. At her New York studio, a wig or some facial hair went a long way, while McCartney’s relatively gender-neutral men’s clothes put the final touch.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #610 (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

In Untitled #610, a man wears a red baggy sweater adorned with chunky black letters from the fashion house’s spring 2017 collection. With his long wavy hair pulled fashionably back, he resembles a middle-aged Timothée Chalamet, the actor and icon of fragile manhood whom McCartney has dressed in the past. His hand confidently resting on the woman’s shoulder, however, hints at traditional masculinity. The series’ women are equally important, for balancing the men’s attitudes and elevating their gender expressions. Curious and attentive, they clutch purses and wear jewelry as emblems of femininity, and Sherman transitions between female characters within the same picture with remarkable ease. “A lipstick or mascara suddenly changed the character’s role into a sister or wife,” she says.

Sherman previously collaborated with fashion brands, including Comme des Garçons and Balenciaga, but the artist is not seeking to use branded fashion as statement on class, which she tackled in her “Society Portraits” of 2008. It was actually her work for Balenciaga that introduced her to digital photography in 2007. After she borrowed a friend’s camera for the shoot, she realized there was no turning back to analogue. Now, she compares her Photoshop time in front of the computer to painting, and says it sometimes bears results that are out of her control.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #465 (2008). Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Digital precision also means encountering her own face in highly pixelated form. Witnessing the physical transformation of her foremost subject has been a part of the process all along. “Using myself in the work now underscores certain elements of aging which I otherwise could be less aware of,” she says, smiling on the other side of the screen, which fluctuates between clarity and blurriness with changing internet strength.

The use of her own image won’t likely change anytime soon, but she is still discovering new modes of transformation. When asked about what she’s up to next, Sherman says, “I plan to bring a crowd into the frame with men, women, children, and older people.”