For her autumn-winter 1986–1987 “Fluxus” collection, in lieu of a traditional runway presentation, Cinzia Ruggeri (1942–2019) created a video projection that featured models performing a series of dramatic scenes in her designs—a “non-show” that is notable both for its transgressive nature and for its pioneering embrace of technology.

Likewise, from her Slap-glove bag (1983), which combined a glove and a clutch, to her Italy boots (1986), which took the shape of her homeland, to dresses inspired by the ancient Mesopotamian architecture of a ziggurat (Homage à Lévi-Strauss, 1983) and crafted from salami string (Abito salame, 1989), it would be limiting to describe Ruggeri’s designs as “fashion.”

She was among the first designers to experiment with electronics, creating emotionally sensitive, interactive clothing—“behavioral garments,” as Ruggeri called them—covered with LED lights that could be switched on and off, for example, or with liquid crystals that would change color based on one’s body temperature.

Cinzia Ruggeri, Nightgown, autumn-winter 1984–1985. Photo: Alessandro Zambianchi. Courtesy of Archive Cinzia Ruggeri, Milan; Galleria Federico Vavassori, Milan.

While training at the Accademia di Arti Applicate in her hometown of Milan, and at her father’s local tailoring company (as well as the Carven atelier in Paris), the late artist and designer became involved in the city’s 1970s radical design scene. She went on to forge a career that transcended creative disciplines, reimagining the form and function of everyday objects and cultural motifs with a fluidity that was decades ahead of its time.

“Clothing became art and art became furniture,” said Sarah McCrory, the artistic director of London’s Goldsmiths CCA, of Ruggieri’s work. It was, she told Artnet News, “an un-hierarchical approach to different media.”

It was also highly influential, with many of her works being referenced (if not always recognized) and even replicated over the years. Among them, her Bed Dress (1986), with its matching pillow headpiece, served as an inspiration for Viktor & Rolf (see: autumn-winter 2005–2006) as well as Maison Martin Margiela (see: spring-summer 2015).

Still, Ruggieri’s oeuvre remains largely overlooked. And so, in collaboration with Italy’s MACRO (Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome), which staged an exhibition of her works in the spring, Goldsmiths CCA has opened “Cinzia Says…”—the largest retrospective of her work to date. The show runs until February 12, 2023.

Cinzia Ruggeri, Stivali Italia (Italy boots, 1986). Photo: Rebecca Fanuele. Courtesy of Archive Cinzia Ruggeri, Milan; Campoli Presti, London, Paris.

The Slap-glove bag, Italy boots, Bed Dress, and Abito salame are all on display, alongside jewelry (think quail-egg earrings), glassware, sofas, sculptures, and more objects of Ruggeri’s making. “Her playfulness lies in a refusal to be pinned down,” said McCrory, who curated the show in collaboration with MACRO’s artistic director, Luca Lo Pinto. “An object is a sculpture, a piece of furniture, or maybe a prop.”

The London show has a special focus on Ruggeri’s film-based work, projecting “Fluxus” footage while reconstructing la règle du jeu?—a sculptural installation inspired by Jean Renoir’s 1939 film The Rules of the Game and filled with autobiographical puzzles, originally presented a few months before Ruggeri’s death in her final exhibition—along with music videos for which she designed clothes.

(The exhibition’s title references lyrics from the song Elettrochoc by Italian pop band Matia Bazar, with whom she frequently collaborated; she also created light and sound installations with Brian Eno.)

An installation view of “Cinzia says…” at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London. Photo: Rob Harris. Courtesy of Goldsmiths CCA.

While she never had the visibility afforded by the era of social media and Virgil Abloh, Ruggeri was the ultimate polymath. “Cinzia did not set herself any limits, either in creating or preserving her works,” Lo Pinto said in the exhibition’s corresponding book, published by Mousse. “Her research was constantly evolving, a perpetually ongoing metamorphosis, chameleon-like in responding to the everyday and cultural environment that surrounded her.”

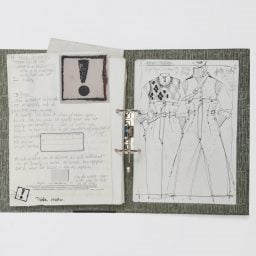

Of her eponymous menswear label, he noted: “While accepting a color, pink, that had been imposed by convention, she was able to create a manifesto for a new man, while retaining her fascination for the possibilities offered by hermaphroditism, and she even suggested that the PCI, the Italian Communist Party, should embrace it.”

This was well before gender fluidity became fashionable, of course. “I love freedom and I hate prejudices,” Ruggeri once said. “I just want to express myself and my ideas in a completely free environment and in different fields and make people smile.”

“Cinzia Says…” is on view at Goldsmiths CCA, London, until February 12, 2023.