Art World

‘Death and Pleasure Are Intertwined’: Novelist Claire Messud on the Emotional Magnitudes of Marlene Dumas’s Painting

An excerpt from the exhibition catalogue "Myths and Mortals," forthcoming from David Zwirner Books next month.

An excerpt from the exhibition catalogue "Myths and Mortals," forthcoming from David Zwirner Books next month.

Claire Messud

The French psychoanalytic feminists of the 1970s and 1980s (Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray) argued that openness of vision and multiplicity of experience is affiliated with the feminine. Jouissance encompasses the idea that just as the multiple orgasm is a privilege of women’s bodies, so, too, the (potentially disruptive) apprehension of multiple textual revelations, a nonlinear experience not directed to a single climax, is an expression of feminine experience. In the creation—as opposed to the consumption—of art, versions of artistic openness (which may occur in the work of artists of any gender) are, by this reading, “feminine,” and work against traditional narrative or visual structures of meaning that both presume and imply a unitary self on a singular trajectory.

Marlene Dumas came of age at the height of these theoretical discussions and has surely absorbed their import, both because of where she was—at the Ateliers ’63 art school in Haarlem, The Netherlands—and because of when she was—in the late 1970s—whether or not she was reading Kristeva, Irigaray, and Hélène Cixous. Transgressive, exuberant (and often funny) multiplicity is unquestionably central to Dumas’s work: in conversation she speaks repeatedly of “openness,” of seeking a fluidity both in her artistic process and in the images she seeks to create. Emphatically a figurative painter, Dumas is driven by gesture and serendipity alike, and by the confluence of diverse inspirations: if a viewer or reader experiences a work as a series of connecting threads, Dumas as an artist—in a manner recognizable to me, as a fiction writer—finds subject and form in a similar way. An artist’s business is something like a magpie’s, or indeed, like composting: you throw a bunch of different things onto the heap and hope something new will grow.

This is quite different from taking an existing story or image and producing one particular vision of it, which was the role of much classical art. Nor is it a straightforward representation of what is. Rather, it is an act of transformation. When Dumas has painted (from photographic sources) familiar icons—contemporary myths, if you will, like Amy Winehouse, or Osama bin Laden, or Marilyn Monroe—she has forced us to see them anew: dead Marilyn, rather than the sexy pinup; Osama as soft-eyed introvert, rather than ruthless terrorist. Similarly, with her unforgettable giant babies, or with what is perhaps her most famous image, The Painter (1994), a portrait of her then-small daughter Helena, naked, glowering, with paint that resembles blood on her hands: in each instance, Dumas overturns visual expectations, marrying the known and the unknowable to create something novel.

In Dumas’s exhibition Myths & Mortals, inspirations are multiple, even in a single painting. She speaks freely about this, deconstructing or tracing different spurs involved in the evolution of particular works. She operates in a realm of myths, in a Jungian sense, where these are “revealed eternal ‘truths’ about mankind’s psychic existence—about the reality of the psyche.”[i] Her touchstones are as often autobiographical (her daughter Helena; conversations with Jan, her partner, or with friends; her own memories) as they are artistic (dialogue with the work of fellow artists, or with that of her predecessors; conversation with classical or ancient artistic forms), political (the inversion of norms; the exploration of current debates, such as the #MeToo movement), or cultural (the depiction of icons whose influence in popular culture, whether positive or negative, is abiding—from Barbie and Naomi Campbell to Nelson Mandela).

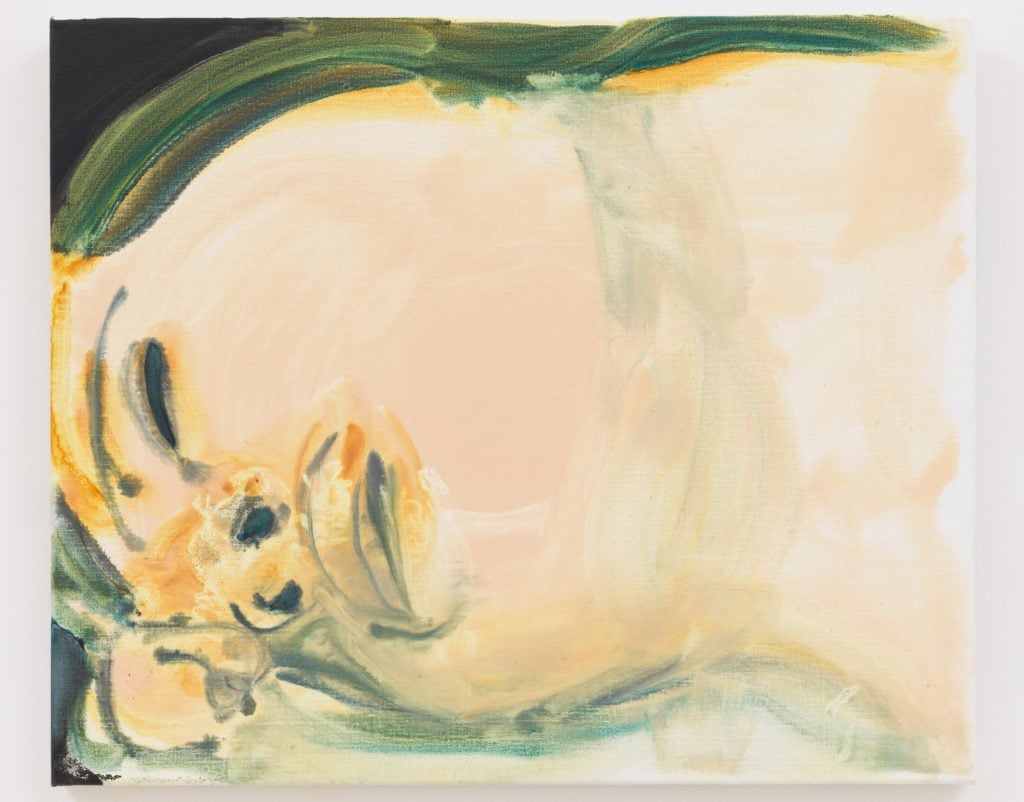

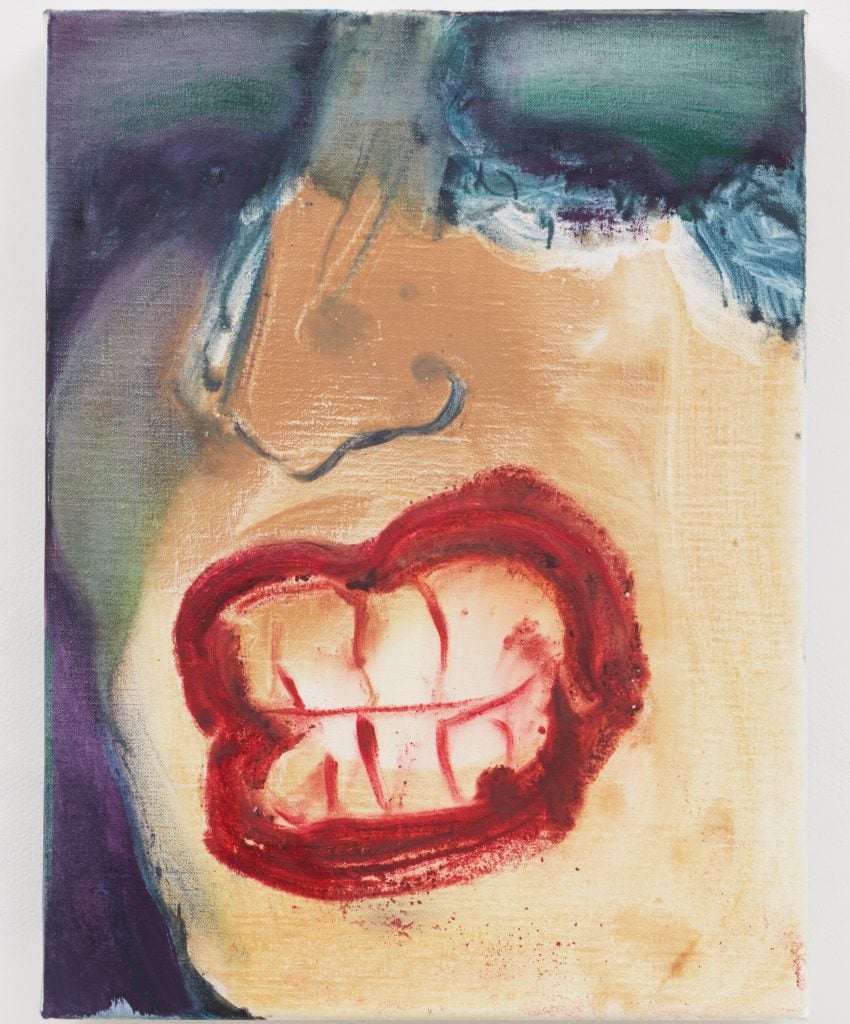

Marlene Dumas, Lips (2018). © Marlene Dumas. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong.

Then, too, challenges inherent in the execution play an important role: the shape of the canvas; the need to balance a composition; the constraints of a mass media image used as her model (often a photograph cut from a magazine or book); the serendipitous flow of the paint or ink upon the canvas, directed but unconstrained by Dumas.

Of a sweet ink wash of a dove, she explains:

Drawing a dove means “competing” with Picasso’s doves. Speed is essential. I had a date with Helena; we were going to go somewhere. I was sitting there, trying to do these drawings, I heard her approaching and I still had no dove—I had all these kitschy doves. Each time, the dove would look like a budgie or some other stupid bird. And then I did this [she points to the image of the dove]; the ink ran. This was all done in one go. Afterwards, to make it look more like a dove, I drew in the little face. So it’s actually two movements. That’s conscious—I used to do it a lot in my old collages, where a work starts with being all gesture, then later you return to it and you just make a slight change, and suddenly it looks like a flower, or it looks like something which, without that addition, it would not.[2]

The fruit of many discarded attempts, this dove is but one in a series of thirty-three ink-wash illustrations of Shakespeare’s rich and sensual early poem Venus and Adonis (based on the story found in Ovid’s poem Metamorphoses), commissioned on the occasion of its translation into Dutch by the Moroccan-Dutch author Hafid Bouazza. These gorgeous images form the core of Myths & Mortals; indeed, the rest of the exhibition was more or less conceived around them.

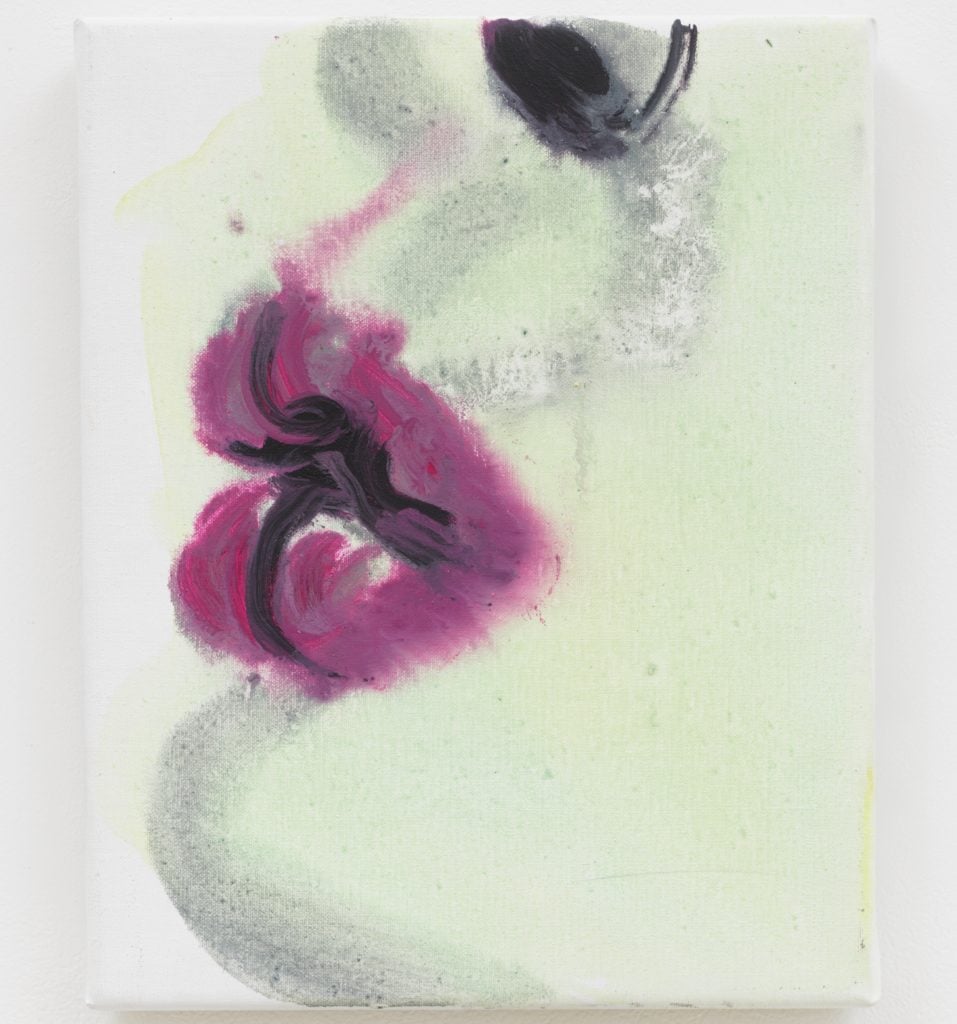

Marlene Dumas, Venus with Body of Adonis (2015-16). © Marlene Dumas. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong.

Dumas explains that she accepted Bouazza’s invitation because “how can I say no to one of the most erotic narrative poems?”

[…]

When Bouazza contacted her, he hoped that she might “honor the story with two or three drawings”; when she agreed, she had no idea that she would embark on a series of such magnitude. But “with Shakespeare, the sexuality and the violence are always very close together, and emotions change all the time,” and thus Dumas found that two or three images would not suffice.

As a child growing up in South Africa’s Western Cape, knowing she wanted to be an artist but uncertain of how to do so, Dumas had imagined being an illustrator; so in a sense the Venus and Adonis project bore an echo of childhood. Bouazza shared with her his large collection of illustrated books, including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and A Thousand and One Nights, but also other fairy and horror tales; she revisited, too, the illustrations of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and those of Édouard Manet for Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven.

In some instances, Dumas was directly inspired by Shakespeare’s language, by the words themselves:

I didn’t do all the drawings directly next to the text, but this one [gestures to the snail] was where Shakespeare expresses how Venus feels seeing the “murdered” body of Adonis for the first time. Her eyes are compared to the snail, “whose tender horns being hit shrinks backward in his shelly cave with pain”—here, I immediately physically understood what he meant. I first read the poem quite quickly, to get the overall feel, but had to reread it many times after for more clarity. Hafid reminded me that a poem, just like a painting, needs more than just a swift glance to reveal itself.

This snail was the first work she produced in the series. It appears in Shakespeare’s poem as a metaphor, and for Dumas, that linguistic turn proved exactly the sort of thread that could connect her viscerally to the text: Venus, in her grief, became present to Dumas in a new way. With the clarity of rereading came a new understanding of the myth itself: “In the beginning, because there are so many old paintings where Adonis is portrayed as much older, or they look as though they’re the same age. I didn’t quite realize just how young he was, that he almost didn’t even have a beard yet. Really, when he says ‘I’m so green and young,’ he means it. Whereas she’s been sleeping with Mars and others—she is an experienced woman.”

Marlene Dumas, Smoke (2018). © Marlene Dumas. Courtesy David Zwirner, NY/Hong Kong.

How to portray Venus, in particular, proved a challenge:

The most difficult was to choose what type of woman to use. The man was easier somehow—I left him as a Mediterranean type; I didn’t try to change him much. But with the woman’s image I had a lot of problems. I did not just want a sort of pinup blonde; but … then what was she like in that [Shakespearean] time? I hoped, through the fusion of different images (models), that one can then identify with all types of women.

Dumas remains keen that her diverse depictions of Venus not be seen as literal, but rather as an exploration of the openness of archetype. The relationship between Venus and Adonis is mythic rather than realistic, a myth that proves particularly resonant and unsettling in this cultural moment.

[…]

In hewing, for the first time, to a literary text, Dumas returned to Munch’s Alpha and Omega, an Adam and Eve–like fable that he wrote and illustrated, and with which Myths & Mortals is in conversation.

Dumas had long been familiar with Munch’s tale:

Long before I did anything with any of this, I always especially liked Munch’s description of Omega: “Omega’s eyes would change; on ordinary days they were pale-blue, but when she looked at her lovers, they became black with flecks of carmine, and occasionally she covered her mouth with a flower.”

It’s similar to the Shakespeare [poem], but in a different way: it goes wrong, but it’s very erotic, it’s an erotic poem … It’s not just that there’s this terrible woman and she devours the man. It’s very sensual: she likes the smell of the flowers and her favorite pastime is kissing. There is humor. There is tragedy, but it’s quite gentle also. It’s drawn very sweetly. There are so many elements in it.

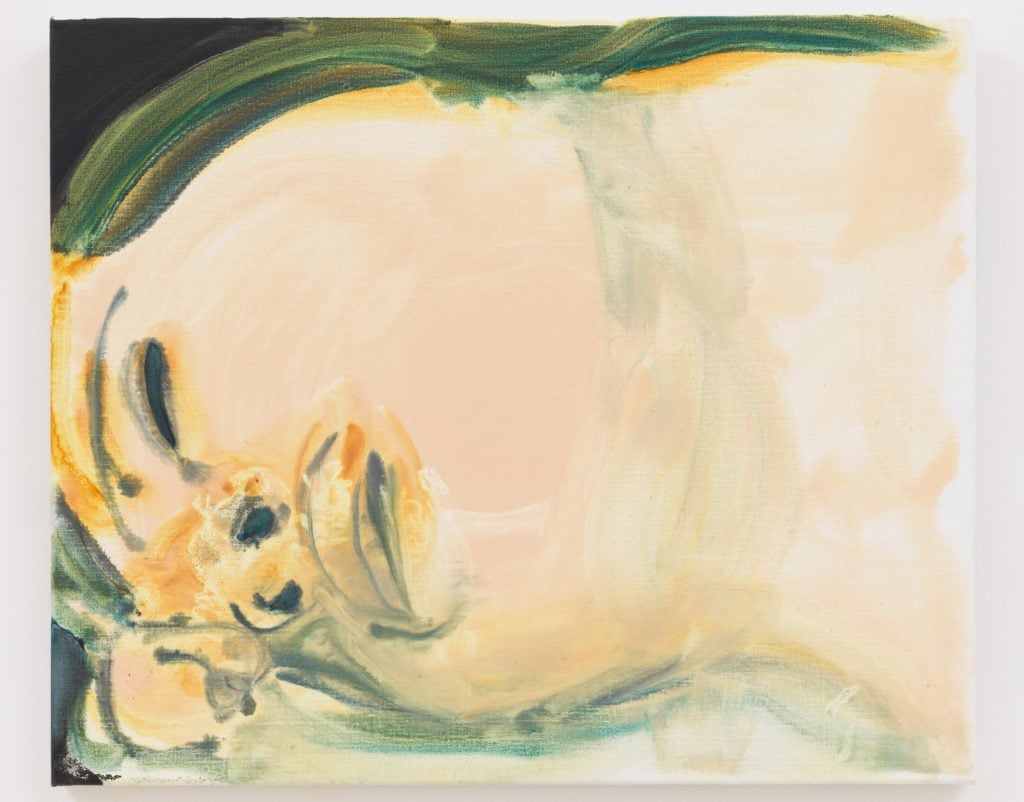

Marlene Dumas, Venus in bliss (2015-16). © Marlene Dumas. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong.

This multiplicity is, of course, intrinsic to Dumas’s oeuvre, as it is to Shakespeare’s poem. It is not inadvertent that her images of Venus and Adonis that appear most erotic actually depict strife or injury: when Venus hovers over a recumbent Adonis, apparently on the verge of a passionate embrace, she hovers in fact over his dying corpse (Venus with Body of Adonis; but also The embrace). When she appears to remonstrate with him, she in fact laments his death (Venus curses Death). When we see her most beautifully “in bliss,” she is not in the throes of love’s consummation, but alone. Even the apparent simplicity of a couple and their love story—of Alpha and Omega, or of Venus and Adonis—is false, as Dumas notes:

This story is full of eroticism, but she does not get him. The boar gets him. And you know, this close friend who died recently, I said to him, “Marcel, I realize I’m talking about the couple all the time, but it’s not only a couple, there’s a third person, because the boar gets him, she doesn’t. And with Alpha and Omega, all the animals come. So actually there are three.” And he said, “But in every couple there’s at least a third person. At least a third person.”

This “third person,” like the unknown import or the unexpected turn—the shadow truth—is always present, even when invisible. In Dumas’s artistic world, certainty is a falsehood. Humor is essential. So, too, is a capacity to encompass darkness and ugliness. Apparent opposites are often perilously close; emotional poles coexist, in palimpsest. Death and pleasure are here intertwined, agony and ecstasy.

Just as the paintings move between emotional poles, so, too, they vary widely in scale. If the small, delicate illustrations for Venus and Adonis are at the heart of Myths & Mortals, an imposing series of full-length portraits, each over nine and a half feet tall, comprises the exhibition’s spine. These seven magnificent paintings take on, among others, questions of agency, Eros, fertility, and isolation. As hung in the gallery, at Dumas’s direction, Spring was the first monumental painting on display: a vibrantly painted woman—her blonde curls reminiscent of Dumas’s own; her age indeterminate, but not necessarily young; her underpants pulled down across her thighs, her firmly planted bare legs red—upending a bottle onto her crotch and rubbing herself with her free hand. Her stance is fierce, her pelvis thrust forward; her face is in comparative shadow. The bottle is clear, suggesting that it may contain water or vodka, or anything else, indeed. Beneath her glows a citron ground: perhaps an illuminated stage, or a painted floor, it seems above all an abstraction, an apt and intense assertion of emotion.

Dumas explains that this painting, its title both signifying rebirth and evoking the rush of liquid dripping down between the figure’s legs, was inspired by a photograph from Haiti:

It’s a voodoo ritual, and it’s vodka and peppers that she’s using. I made it more suggestive, more like water, keeping that open. I believe you need to be a bit in love with what you do: you have to believe it’s worth doing. I remember when painting this, I was really enjoying being alive. And I thought: Yes, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”[3] Women especially like this work.

She laughs again as she says this; but there is serious import in this portrait of a not-young woman so powerfully sexual and utterly independent in her pleasure. “When I chose this image, it was for the way she stood. It’s fantastic that she stands like this, and so dynamic.” Dumas is, if you will, creating a new myth for women: a myth in which woman is a sexual subject—the opposite of an object, responsible, autonomous, and assertive. This piece is, moreover, engaged in conversation with Venus and Adonis: when you’re past forty, Dumas explains (she is now in her mid-60s), and you encounter someone younger and attractive, you experience “the awkwardness of liking someone but not really knowing what type of role or relationship [it may be].” Being Venus, indeed, is as awkward as being Adonis.

Marlene Dumas, Awkward (2018). © Marlene Dumas. Courtesy of David Zwirner.

The uncertainties of attraction are compelling in their many configurations. Each first kiss is born of risk. Awkwardness is inherent in Eros; indeed, awkwardness itself can be erotic. In Awkward, Dumas conveys this truth with thrilling tenderness. The canvas depicts a young couple in profile, holding each other by the arms, her foot sweetly riding on top of his. Between them stretches a sharply defined line of pale light that extends the length of their bodies, interrupted only by their arms. They themselves are blue; behind their backs pulse glimpses of red, as though their lust has not yet seeped into the space between them. They are decidedly awkward; they hover on the cusp of love; they are at once mortal and immortal. It is impossible not to recall Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn”: “What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? / . . . Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss, / Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve; / She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, / For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!”

Dumas didn’t have Keats specifically in mind, but she might as well have done. She shows me an image of a Greek vase in a Dutch newspaper (from almost twenty years ago) that influenced Awkward. “I used to think it was a man and a woman, but it is a man and a young boy. . . . It doesn’t really matter what sex you are: it’s about two people, trying to touch one another.” The figures took form out of the painting process itself. The awkwardness arose organically. The incipient lovers are, as a friend of Dumas’s observed, “playing footsie”; they’re holding hands; the rest is yet to come. As Keats writes, “More happy love! more happy, happy love! / For ever warm and still to be enjoy’d, / For ever panting, and for ever young.”

The affect of two more of the tall paintings, Bride and Birth, emanates in each case from a different emotional realm. In discussing the first work, Dumas explains, “The veiled women in white always fascinated me. The bride eventually evolved into a mummified Egyptian. She’s extremely gothic.” This work, Dumas adds, emerged as a conversation in her imagination with the illustrations in Bouazza’s book collection. “I come from a modernist background. As a child you illustrate, or you play with narrative; but as a painter you want your works to have as little narrative as possible.” The Venus and Adonis project, she implies, freed her from certain longstanding tacit artistic constraints and enabled new types of cross-pollination in her work.

Birth, as magnificent and arresting an image as Spring, depicts a naked female figure, vastly pregnant, her hands raised on either side of her head. In preparation for this painting, Dumas looked at many goddesses, including Inanna, also known as Ishtar, the Sumerian goddess that anticipated Aphrodite/Venus, worshipped as a deity of love, sex, fertility, and war, among other attributes. Inanna is often depicted with her hands in this pose. In the early Christian tradition, this gesture is seen also in the orante, a female figure in meditative prayer, evoking a state of peace with the universe. It is an ancient pose, replete with spiritual resonances, made only the more forceful by the unborn child at the painting’s center. The fact that the woman’s face is unreadable—is this defiance? is it alarm? resignation? or simply quietude?—is apt. Surely for an archetype, an immortal, openness is key: each mother will experience the imminent birth of her child differently; contained within that experience will be a gamut of emotions. Dumas allows here for the jouissance of maternity, many things at once.

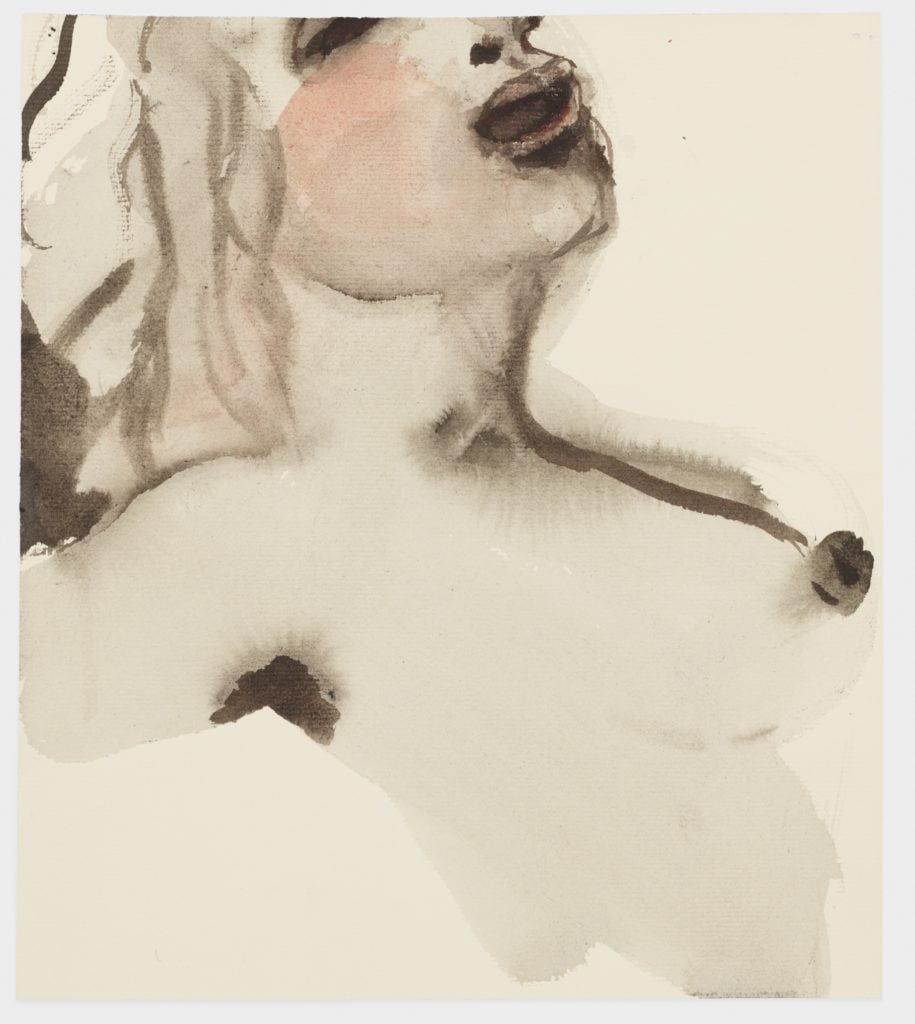

Marlene Dumas, Teeth (2018). © Marlene Dumas. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong.

[…]

For the viewer, each experience of these works will similarly entail a particular combination of our own autobiography and political and cultural history, along with perhaps the mood or moment in which we stand before the painting. Part of Dumas’s genius is always already to have understood this fact, and to approach her artistic process with this knowledge. Whatever the words one uses to articulate the result—“openness,” “multiplicity,” “jouissance”—the effect is the same: these are paintings that encourage each viewer to push further into the specificity of their encounter. This is no realm of abstraction; nor is it one of finite and directed significance. Dumas’s subjects are at once myths and mortals, simultaneously familiar and strange. Awkwardness, the angle of a lover’s foot, the protrusion of a nipple, the curve of a swan’s neck, the roil of tongues—by these visceral specificities each of us will be tied to Dumas’s world and her work. She offers, in these paintings, a multitude of possible threads.

Dumas says of Shakespeare’s raw and gutting poem, “The more I read it, in the end it seemed very clear”; similarly, from the monumental ferocity of Spring or Birth to the tender intimacy of The snail or The flower in the Venus and Adonis series, each work speaks clearly, and distinctly, to each of us. Connection—whether in love or in art—entails risk; risk entails awkwardness. And it is through vulnerabilities that, as humans, we speak most profoundly, from the heart.

This excerpt is from the essay “Open To Interpretation” by Claire Messud, which appears in the publication Marlene Dumas: Myths and Mortals, forthcoming from David Zwirner Books on June 18, 2019.

Notes:

[1] Donald Kalsched and Alan Jones, “Myth and Psyche: The Evolution of Consciousness,” exhibition text, Hofstra University Museum, Hempstead, New York, 1986; www.cgjungny.org/d/d_mythpsyche.html (accessed November 16, 2018).

[2] All quotes by Marlene Dumas are from a conversation with the author, August 5, 2018.

[3] From Dylan Thomas’s poem “Do not go gentle into that good night,” first published in 1951 in the journal Botteghe Oscure; see Dylan Thomas, Collected Poems 1914–1952 (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1952), p.116.