Archaeology & History

Some of the Oldest and Most Revered Cave Paintings in the World Are Under Extreme Threat Due to Climate Change

A new report suggests that the cave art in Sulawesi is deteriorating at an alarming rate.

A new report suggests that the cave art in Sulawesi is deteriorating at an alarming rate.

Sarah Cascone

For tens of thousands of years, prehistoric paintings have survived in the caves of Sulawesi, an Indonesian island, offering an invaluable record of early humanity’s creative impulses.

Now, those Pleistocene-era works, created between 20,000 and 45,500 years ago, are in danger of being lost forever due to the ravages of climate change.

Sulawesi’s cave art is weathering at an alarmingly rapid rate, and the planet’s rapidly warming climate is to blame, reports a new study in the journal Scientific Reports. The findings were based on examinations of 11 sites in the island’s Maros-Pangkep cave complex conducted by archaeological scientists, conservation specialists, and heritage managers who were concerned about the degradation they were seeing.

“We used a combination of scientific techniques, including using high-powered microscopes, chemical analyses, and crystal identification to tackle the problem,” the research team wrote in the Conversation. “This revealed that salts growing both on top of and behind ancient rock art can cause it to flake away.”

The technical name for what’s threatening ancient cave art is haloclasty, also known as salt efflorescence or salt crystallization.

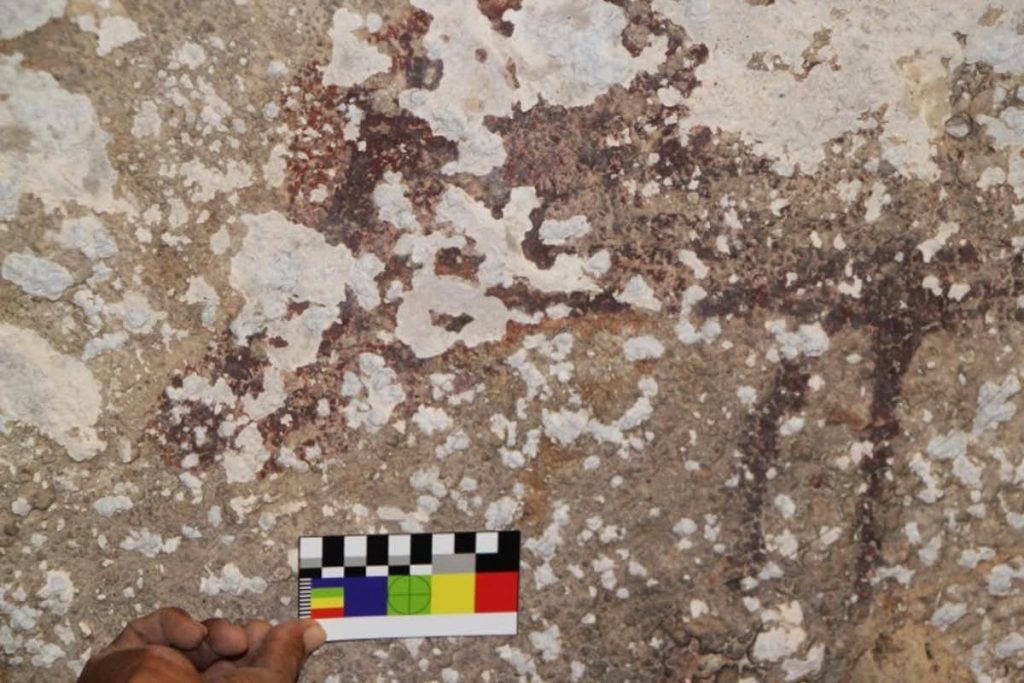

Expanding and contracting salt crystals are causing rock art to flake off the cave walls. Photo by Linda Siagian.

Salt crystals in the cave grow, shrink, and swell based on changes in temperature and humidity, which have become more pronounced in Indonesia in recent years, accelerating deterioration as the paintings blister and peel off the walls.

“Climate change impacts are worse in the equatorial tropics—Australasia—because of the unique climate here. It is the most atmospherically dynamic place on Earth,” the study’s lead author, Jill Huntley, a research fellow at the Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit at Griffith University in Australia, told CNN. “The tropics can experience up to three times the temperature increases under climate change compared to other parts of the world.”

An increase in greenhouse gases is leading to more extreme weather patterns, with severe droughts followed by increasingly heavy seasonal monsoons, creating the ideal conditions for haloclasty—and a nightmare for preservationists.

Combined with forecasts for rising temperatures globally, as well as an increase in extreme weather events, the findings in Sulawesi “have grave implications for the conservation of this globally significant cultural heritage,” the study warned.

Climate change is leading to rapid deterioration of ancient rock art in Indonesia. Photo courtesy of Griffith University.

Indonesian rock art was typically made near cave entrances, rather than deep inside rock formations, making it more exposed to both light and the elements. That’s particularly significant considering the natural disasters that have struck the country in recent years.

The significance of Indonesian cave art, first discovered in the 1950s, only become clear since 2014, when scientists used new dating techniques to determine that some of these paintings were just as old—if not older—than European Ice Age-era cave paintings, previously believed to be the world’s oldest art.

“This is us. These are our ancestors, some of the very first humans in this region,” Huntley told Channel News Asia. “The discovery of this art has literally re-written textbooks.”

The new dates for the Indonesian artworks were obtained by testing calcium carbonate deposits, or “cave popcorn,” that formed atop cave paintings. The technique, which is not without controversy, is believed to offer a minimum age for the painting underneath the mineral crust.

In January, the world’s oldest-known representational artwork, of a group of Sulawesi warty pigs, was discovered in the island’s Leang Tedongnge cave.

There are other human-made threats to ancient cave art, thanks to limestone quarrying for the cement and marble industries, but the study said that “global warming should be regarded as the greatest threat to the preservation of the ancient rock art that survives in Sulawesi and other parts of tropical Indonesia.”

The study’s findings suggest that it is all the more important that archaeologists identify, study, and document Indonesian rock art—particularly through high-tech 3-D scanning—before it disappears forever.

“It’s a race against time,” Huntley warned.