Hamza Walker moved from Chicago to Los Angeles for his new job as director of contemporary art nonprofit LAXART on Christmas Day 2016, the month after Donald Trump was elected president. The atmosphere at many arts organizations was grim, to say the least. Especially at that moment, Walker told Artnet News in a recent phone conversation, the usual kind of art show didn’t seem to measure up to the moment.

“There are figures who are out there making art, and what is their artwork about? You go through the art, and that’s your lens for looking at the world,” he said, summing up the customary curatorial method. Instead, the approach he urged in a staff meeting a year into his tenure was, “Let’s move the art out of the way and just look at the world. What speaks to issues of national value?”

For him, there was one glaringly obvious answer: the decommissioning of Confederate monuments, a phenomenon he never thought he would live to see. Walker conceived a fiendish idea: Why not stage an exhibition in which, removed from their places of pride, these statues could be evaluated not only as propaganda for genocide but also as art objects? And why not invite contemporary artists to create works in response to them?

Last week, Walker formally announced that this exhibition would become reality on the new Hope and Dread podcast, hosted by Allan Schwartzman and Charlotte Burns. It is currently scheduled to open in 2023.

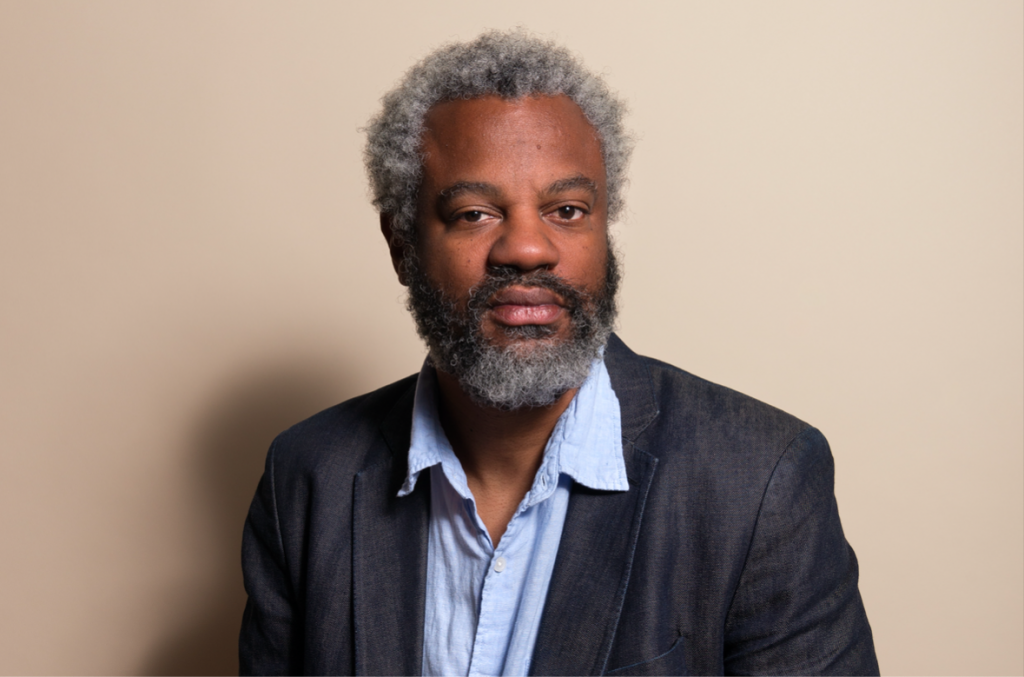

Hamza Walker. Photo by Esteban Pulido, courtesy of LAXART.

The first wave of decommissioning, Walker points out, began after white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine churchgoers at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2015. The next year, in response, Charlottesville, Virginia, and New Orleans, Louisiana, officially approved the removal of their monuments to the “Lost Cause.”

But the removal of these toxic public artworks raised a question: what to do with them? Destroy them? Leave them in place but add to them somehow, for example with educational materials to add context? Experts offered a wide range of imaginative suggestions. Walker thought his show could be a thoughtful way to road-test one frequent (but sometimes vague and simplistic) response: “Put them in a museum.” (A history museum is currently planning a display of a monument to Robert E. Lee.)

Just as a Hollywood film sometimes needs a big name attached in order to get the green light, Walker felt he would need a co-organizer with star power to pull off his plan. In the meeting where he proposed the show, he said, he added, “I think we need to do this with Kara Walker.”

“My staff just looked at me,” he said. “It was so self-evident as to almost be stupid. You could almost miss it.” Having known Walker (no relation) for years, he was able to quickly get her on board, and then to get seed funding from the Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation and secure a venue: the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.

Since then, little has proceeded so smoothly, even as the show’s relevance has only grown. In summer 2017, white supremacists gathered in Charlottesville for a pro-monument rally that turned deadly. This launched the issue into the global consciousness on a new level—especially when, in a press conference, Trump failed to condemn the rioters, and even offered them encouragement. And, while the successive waves of monument removals gave Walker an ever-growing roster of potential loans for the show, it also made his project that much more sensitive, leading him to keep it under wraps.

To ask officials to lend their toppled monuments, however, Walker had to disclose details of his planned exhibition. In these proposals, he named some artists and works that might be appropriate—but before he had approached the artists themselves. After these proposals were presented in public meetings, they leaked before a checklist was finalized. (Awkward!) In interviews, Walker has declined to name the participating artists.

But the bigger problem has arisen in securing the monuments in the first place.

“Who is the steward of the object?” he asked. “Is it city hall? If so, do they want to make this decision? Maybe it’s, ‘We took the things down, but who’s going to deal with them?’ We came in at a moment when places are still trying to figure that out. You might have progressive forces in city hall but conservative forces on the historic preservation committee,” or vice versa.

The question of ownership is one that is not only settled in the streets, as in Charlottesville, but also in the states. North Carolina, for example, passed a law in 2015 preventing the removal of Confederate monuments except under certain circumstances. Such legislation, Walker explained, has had a chilling effect, since elected officials fear litigation. At moments, he said, it has seemed it would be simpler to borrow a chunk of a cathedral from Italy (a country notoriously protective of its cultural heritage) than to stage the show he’s working on.

But he hasn’t given up.

“It’s quite engaging,” he says, with an ironic note, “to work on something that is unfolding in real time.”