Law & Politics

Congressman to Appeal Removal of Art Showing Cops as Pigs, Citing Free Speech

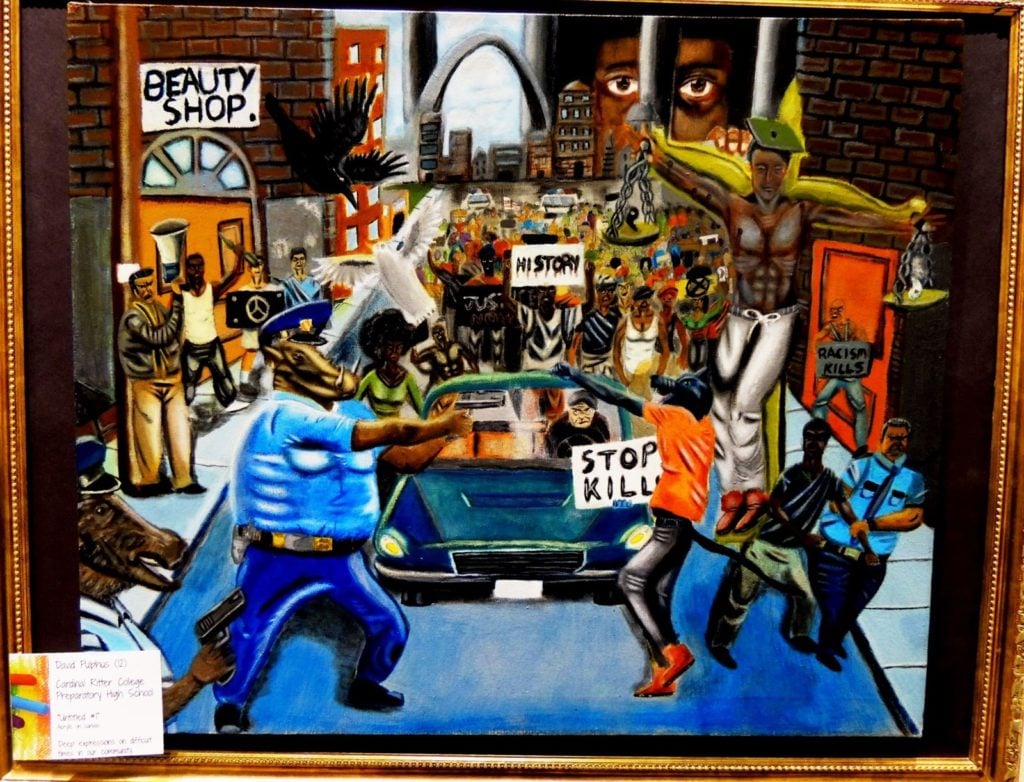

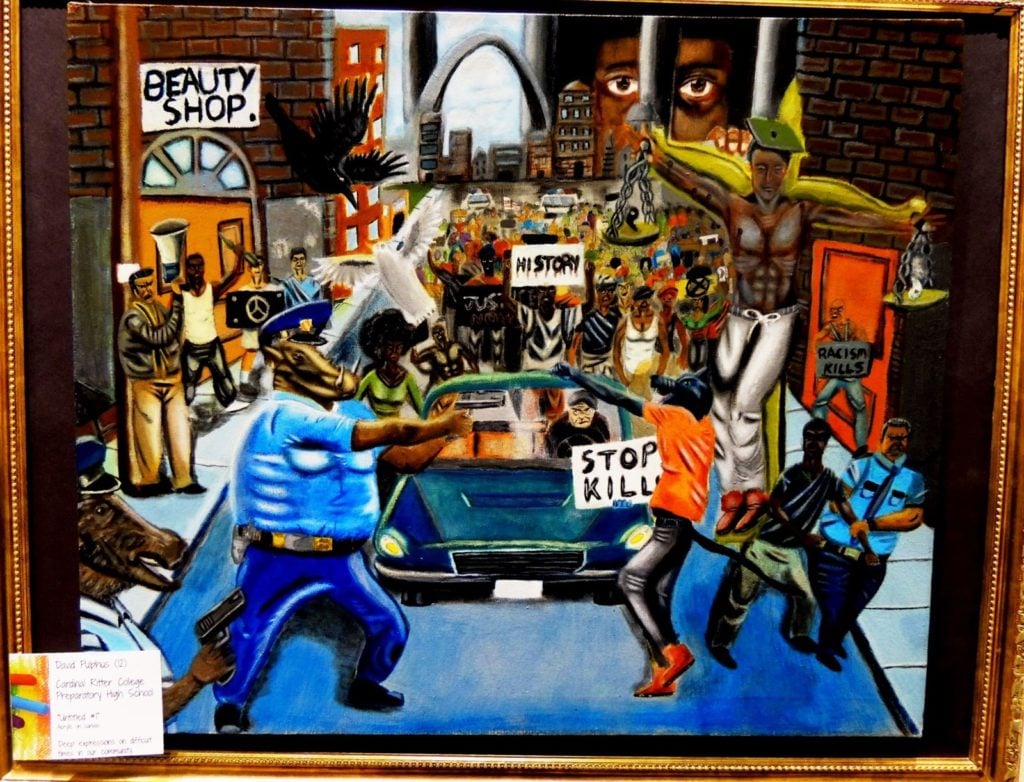

The canvas was inspired by Black Lives Matter protests; some call it "anti-police."

The canvas was inspired by Black Lives Matter protests; some call it "anti-police."

Brian Boucher

A Missouri Congressman is appealing a judge’s ruling in a long-simmering dispute involving a 19-year-old’s painting that shows policemen as pigs. The work was on display at the US Capitol as part of a student art competition and has outraged some Republican Congressmen and some in the conservative media, who have branded the work “anti-police.”

United States District Judge John D. Bates, in Washington, DC, ruled against Missouri Congressman William Lacy Clay as well as David Pulphus, who created the painting and is one of Lacy Clay’s constituents. They claim that their First Amendment rights to free speech were infringed upon when the Architect of the Capitol, Stephen T. Ayers, removed Pulphus’s painting from a display of student art. Bates, in a decision released Friday, ruled that while Pulphus has standing to sue, the judge won’t grant him a preliminary injunction, which would require that the painting be re-installed.

Lacy Clay and Pulphus plan to take the case to the Washington, DC Federal Circuit.

“Our nation was founded on the very principle of freedom of speech, and there are few places where that core freedom warrants greater respect than the U.S. Capitol,” say Lacy Clay and Pulphus in a statement. “That is why we are confident that the U.S. Court of Appeals will eventually vindicate not only our legal rights, but those of the American people. We believe our Constitution simply cannot tolerate a situation where artwork can be removed from the Capitol for the first time ever as a result of a series of ideologically and politically driven complaints.”

The case hinges on the question of whether the hallway where the painting hangs is a public forum, in which First Amendment rights would be protected: Does the competition itself constitute “government speech,” where the Architect of the Capitol, who oversees the competition, would have the right to restrict speech? The artworks on view in a government-run venue would seem to have a government imprimatur. The judge notes, however, that “the government speech doctrine is still evolving, and it is not entirely clear how courts should distinguish between non-public forums and government speech.”

The painting in question depicts a protest in which a demonstrator is prominently shown as a wolf. A man carries a sign reading “Racism Kills”; a black man hangs on a cross whose arms form the scales of justice; another black man looks out over the scene from behind prison next to the Gateway Arch, of St. Louis. At center of the painting is a policeman with the head of a pig (or boar), pointing his gun at the wolf-like protester. The work took as its impetus the police killing of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, which is part of Lacy Clay’s district.

The winning painting, displayed on Capitol Hill, resulted in a comical back-and-forth. Seemingly emboldened by their party’s winning majorities in the House and the Senate as well as winning the White House, Republican Congressmen repeatedly removed the offending painting from the wall. Representative Lacy Clay doggedly returned it each time. The rationale offered by the Republicans involved a rule in the competition’s “suitability” guidelines, which prohibit controversial or political subject matter. All the same, as Lacy Clay pointed out in his suit, other paintings showed subjects such as police misconduct, homelessness, and war.

Stephen T. Ayers ruled after the uproar that the painting was in violation of the rule, but Lacy Clay filed a First Amendment lawsuit in February, saying the painting had hung for months without dispute and that Ayers shouldn’t have made the ruling about suitability retroactively. A debate broke down along predictable lines: Police unions denounced the painting, while organizations like the College Art Association and the National Coalition against sponsorship lined up in support of it. The suit claimed that the controversy not only violated Pulphus’s First Amendment rights but also demeaned him in the public sphere and inflicted harm to his reputation. Moreover, Lacy Clay maintains that his duty to represent his constituents is being impinged upon, since no painting from his district currently hangs in the competition gallery.