Soft scraping, dabs of solvent, the methodical swabbing of a painted surface inch by inch: art restoration videos are an ASMR goldmine.

In this niche genre, conservator Julian Baumgartner is a bona fide celebrity, with a YouTube channel that has amassed millions of views. Beyond their satisfying soundtrack, Baumgartner’s videos capture the detailed methodology and meticulous approach to restoring the works that pass through the doors of Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration, the Chicago studio founded in 1978 by his father, R. Agass Baumgartner, a Swiss immigrant.

Julian Baumgartner learned the intricacies of the trade as an apprentice to his father from 2000 until his passing in 2011. Four years later, Baumgartner decided to make a video of a restoration, despite having no firsthand filming experience. “That’s a modus operandi among conservators in general: if you need a new skill, you teach yourself,” said Baumgartner.

He appears to have succeeded, his channel having recently surpassed 1.5 million subscribers. We caught up with him to chat about his restoration pet peeves, revelatory moments, and why, exactly, he thinks people are so fascinated with his videos.

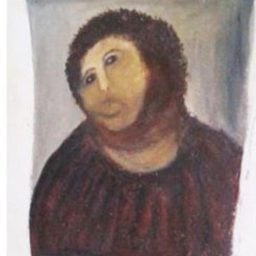

Courtesy of Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration.

What was the first video you ever made, and why did you decide to start making videos?

I received a really grand William Merritt Chase painting that was horribly damaged. I thought it would be great to document the process and make a really romantic and beautiful nod to conservation. So I hired a videographer and we made that project. I threw it up on YouTube, where it languished in obscurity and I kind of forgot about it. At the time, I was focusing on Instagram, where I was having direct interactions with other conservators and was generally really satisfied. Our Instagram account went viral in 2016 and then our audience was much bigger. I realized the stories I wanted to show just couldn’t fit Instagram’s format at that time, so I decided that I’d take another shot at YouTube. The rest is history, so to speak.

Your videos range from short clips to series that stretch well over an hour. Still, these are condensed time frames in relation to your actual process. What’s the longest you’ve ever worked on a single artwork?

I think the longest I’ve ever worked on one piece was about nine months, on a painting that called for a paint film transfer. An incredibly damaged painting had been glued to plywood and then covered with a scrim of silk and polyurethane. The polyurethane had to come off the front of the work, but it had to come off of the plywood, too. In the process, I discovered that the canvas was so rotted and deteriorated and there was almost nothing left, hence why it had been mounted to plywood, so then I had to remove the paint layer from the canvas, which was effectively completely disintegrated. That process was nine months of very methodically, very slowly working through it—an hour or two a day, and maybe none the next day. Eventually, as you go brick by brick, step by step, you reach the finish line.

What is the most indispensable tool in your studio?

The greatest tool I have is my brain, right? It gives me the ability to synthesize information and be creative. Then, on a more practical level, my hands, because though I may theorize or research an interesting approach, I still have to execute it. Conservation is still a craft. Despite all of the scientific advances, the practitioner still needs to have the technical ability. In terms of equipment, without a doubt, my hot tables: These are at the heart of every modern conservation studio. You can certainly practice conservation without them, but it’s like being a chef without a range or a woodworker without a table saw. There are ways around it, sure—conservators figured out ways for many years before the advent of heated vacuum tables—but they allow for a degree of control and a broad range of treatments.

Courtesy of Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration.

In your videos, you often kid around about your hatred of staples that earlier conservators or owners have used. What are some of your restoration and conservation pet peeves?

Staples, of course! That’s just a joke that arose from me complaining in one of my videos. In reality, I’d say my biggest frustrations are with well-intentioned individuals whose hearts are in the right places but who don’t have the technical and intellectual know-how. It’s really frustrating to receive a painting that has been worked on in the past, and the work isn’t good or the materials are incorrect. I have to undo that just to get to a point where we can start to properly address the issues at hand. It costs time and money and it is completely avoidable. I think of home contractors who go in to renovate a home to find that somebody has done something wonky—it’s going to slow down the project.

Another pet peeve is seeing contemporary work with antiquated materials. I see many people using approaches that were popular a hundred years ago. I just have to wonder why: we have newer, specifically designed materials that have been shown to be much safer, much more stable, and more easily reversible. If I had to distill it down to one particular approach that I find mind-boggling, it’s rabbit-skin glue linings. We know so much about the fallibility of rabbit-skin glue and what it does to canvases that I have a hard time understanding why it would be an option.

I’ve heard conservators say, “Well, it’s traditional.” My response is that 200 years ago, when doctors had to amputate, they gave you a shot of whiskey and told you to bite on a stick. In fact, treatments and materials that we are using now may be viewed as archaic in a hundred years. And that’s good, it means the conservation has evolved. We conservators are just like parents who want their children to succeed beyond their own capacities.

What’s the most satisfying part of restoring a painting? What’s the most grueling or tedious part?

Everything and everything! There are two aspects that are incredibly rewarding. One is the cleaning process. I might be the first person in over 200 years to see a painting as the artist saw it. There’s kind of a little magical moment where I get to see the piece as it was originally intended. For a brief moment, it is private and very special.

The other rewarding aspect is the retouching process. That’s where all of the damage gets reversed and the piece starts to come together. The tear in the face gets retouched away and the sitter becomes a person again. Or the hole in the landscape disappears and you can see the forest, not the trees.

Those are also the most frustrating parts, though, because they are very intense. Cleaning is a reductive process: you have to be very, very careful and be very, very focused. If you remove something, you can’t put it back. It takes a lot of intellectual and emotional energy. Retouching, meanwhile, is a process of extreme restraint. We have to be constantly trying to do as little as possible while achieving the maximum results. We can’t just overpaint the background, even though there are 10,000 little pieces of paint loss; we have to restrain ourselves to only adding paint where it is missing. Sometimes the damage is really extreme and it seems impossible to unify the image. You know, if you’re in the right mindset, you relish it. If you’re not, you step away and find some lower-hanging fruit.

Do you have any favorite work or proudest moments?

The cheeky answer is the next one, right? The one that’s yet to come through the door. I’m proud of all the work that I’ve done, and I’m most proud of the ones that have tested me and really stretched me beyond my comfort zone. Big names aren’t really all that interesting. I joke with my clients that you don’t want to go into brain surgery and have your doctor go, “Oh, it’s you? Oh, gee, I’m nervous now.” You don’t want your conservator to see your Monet and say, “Oh gosh!” You want them to be unaffected. The best works are the ones that forced me to research new materials and find new solutions and techniques.

Now, let’s really get down to it. Why do you think people are so fascinated by these videos?

I’ve had many years to think about it. I think that it comes down to a couple of factors. At its most basic, the world of art is at arm’s length for most people, and the world of art conservation is even further afield—that this even exists is something that the majority of people have no concept of. To see it, it’s revealing something new that people can peek into.

Beyond that, there is a long history of watching engaged, creative, dedicated people work through a problem with their hands. A TV show like This Old House is a 40-year success because we love watching craftspeople in love with their craft and plying it beautifully.

It’s peeling back the curtain, seeing that the Wizard of Oz is not an all-powerful wizard, he’s just a man who’s working incredibly hard, or Mr. Rogers taking us on a tour of a crayon factory and it dazzling us. The expansion of a knowledge base feels good.

It’s soothing, for whatever reason. I find these videos really calm me down.

There is an aspect of wholesomeness to the videos: there’s no antagonist. There’s a certain level of dad humor and corny, harmless jokes that resonate with people. There’s no yelling or swearing or chairs getting thrown. Nobody’s the bad guy. Everything is focused on a positive resolution, and when there are surprises it’s to nobody’s fault or detriment. It feels good to watch. The past couple of years have been existentially difficult, and getting lost in a half-hour video that doesn’t make you feel bad—that momentarily captures your entire intellectual and emotional capacity and rewards you for that—is satisfying. These paintings start off in a bad state and you know by the end, there’s going to be a great transformation. Success is waiting for us at the end. Conservation is not magic; it’s really just a dedicated craftsperson working with their hands, employing materials and techniques with patience and care. If I in my studio with a scalpel and some brushes can save this magical piece of artwork, then you at home—with whatever tools you have, whatever capacity you have—can effect a positive change somewhere in your life.