Art World

Intimism Revisited: The New Generation of Artists Inspired By Their Private Spaces

The specter of Pierre Bonnard looms large and is fueling an Intimism revival. Artists are finding inspiration in their everyday surroundings.

The allure of and fascination with the intimate vignettes that make up everyday life have been an ongoing source of inspiration for generations of artists—the way a coffee table or nightstand is arranged, the view from a studio window, the books, plants, and other miscellany that accumulate (or are curated) on a bookshelf.

Focus on these personal spatial moments within art coalesced into a formal movement at the turn of the 20th century with Intimism, with none other than French artist Pierre Bonnard being one of its most notable pioneers. While Bonnard is one of those juggernauts of art history whose name is bandied about in conversations around Post-Impressionism and its legacy, the somewhat more niche Intimist movement and his achievements within it offer new perspectives on another Intimist-style trend happening today, just over a century later.

Alec Egan, Look Out (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles / New York.

Despite containing stylistic overlaps with earlier Impressionism, Intimism stood apart both formally and aesthetically; representational precision of subject, light, and color were not a primary concern, and in fact the opposite was true. Bold palettes, perspectival distortion, and texture were prized instead for their ability to convey a sense of emotional, psychological intimacy.

It is exactly these inclinations that can be traced in the work of a range of American artists today, whose paintings embody a decidedly contemporary Intimist trend—but with a twist. The idiosyncratic depiction of everyday objects and domestic scenes are rendered with hyper-saturated palettes and with a degree of detail, either in its precision or abundance, that is as intriguing as the subject matter itself. The mundane is made extravagant.

Cooper, Mount Garden Party (2024). Courtesy of Maddox Gallery, London / Gstaad.

Andrew Cooper, who goes by the mononym Cooper, has cited artists ranging from David Hockney to Andy Dixon as influences, and creates paintings that act as subjective snapshots from his own life and home—wherever that may be. In the instance of Mount Garden Party (2024), Cooper was undertaking a residency with Maddox Gallery in London. Despite being a background element, the rendering of the Victorian style wallpaper, a hallmark in many London homes, vies for foreground attention, exploding forth with flowers and foliage. The vase of flowers, record player, plants, and book become secondary but no less relevant to identifying the personality of the space as perceived by the artist.

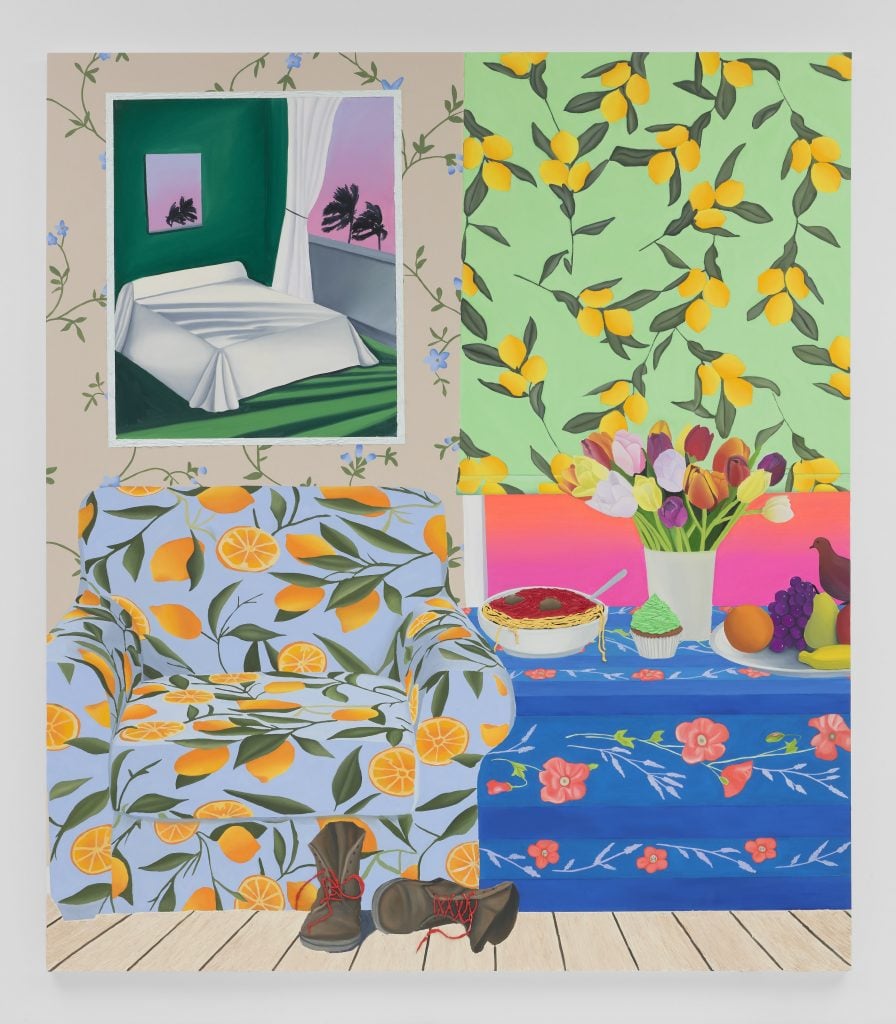

Hilary Pecis, Summer Tulips (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Timothy Taylor.

Similarities in the employment of pattern can be seen in pieces by Hilary Pecis, but with emphasis placed on vivid fields of color and geometric precision, resulting in the recognizability of the tableaux being destabilized. A framed print on the wall, crystal vase of flowers, or open book, as can be seen in Summer Tulips (2023), are at once familiar and foreign, signaling a portrait of a space but in a manner that only exists psychologically. And the juxtapositions between various elements highlight Pecis’s proprietary style of perspective, wherein the quality of her hues and rendering of pattern simultaneously flatten the perception of three-dimensional space.

The attention to precision is perhaps no more manifest than in the work of Alec Egan. Fields of bold pattern and color across wallpaper, linens, upholstery, and curtains threaten to overwhelm the eye but are harnessed by meticulous linework delineating form and space. The effect could be described as a sort of sterile vibrancy—idealization taken to the brink. Even in his more compositionally minimalist paintings such as of architecture or landscape, swathes of hyper-saturated ombré skies prohibit any sense of true reality, instead appearing more like a daydream or romanticized reverie.

Together, as an aside, Cooper’s, Pecis’s, and Egan’s work brings attention to wallpaper as an unsung hero of contemporary art.

Alec Egan, Miro’s Corner (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles / New York.

Highlighting the purposeful and personal within this Contemporary Intimist moment are the paintings of Anna Valdez, who refers to Bonnard as an influence and uses curated collections of objects in her work as storytelling devices. Nearly every inch of the compositional frame is filled with things, and the inclusion of items such as textiles, decorated porcelain or pottery, or exotic shells give the effect of endless pattern and texture, sometimes seeming discordant, at others surprisingly cohesive. Nothing included, however, appears by happenstance: the specific arrangement of veins and hues of various species of houseplant or collection of stacked books allude to the Valdez’s personal world and singular artistic vernacular.

Anna Valdez, Glass Domes with Cockatiels and Coyote Skull (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Hashimoto Contemporary, New York / Los Angeles / San Francisco.

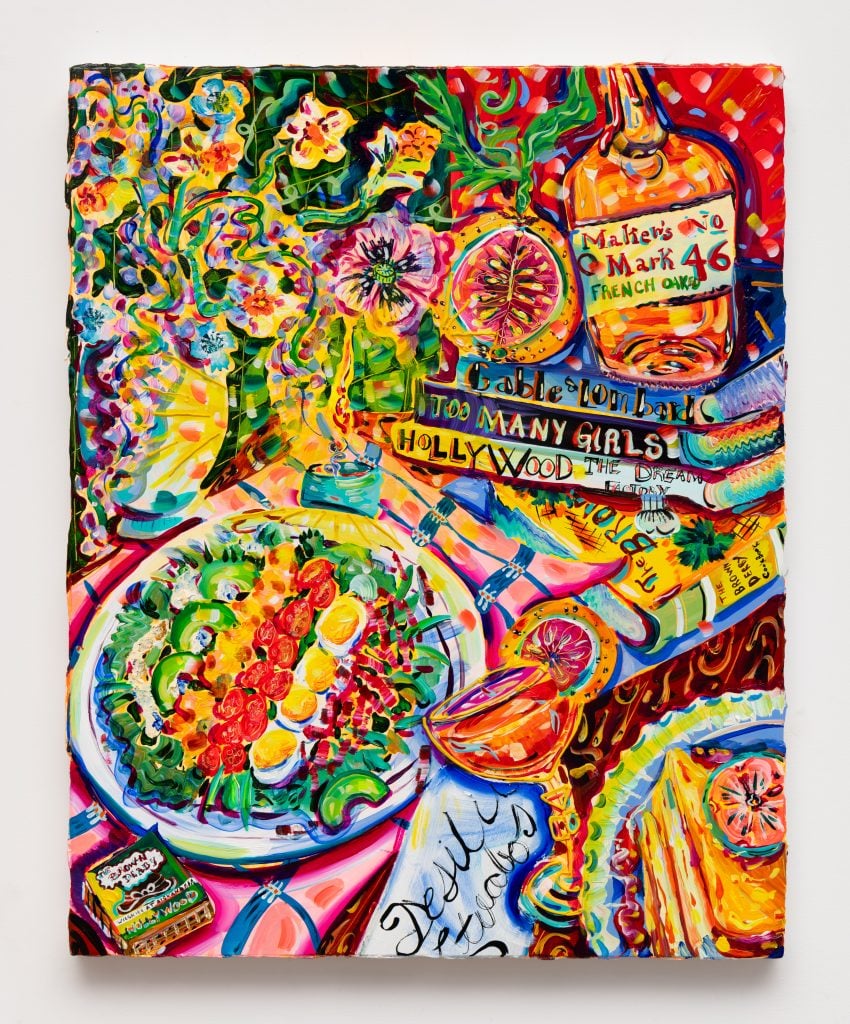

Born in 1993, the youngest of this particular sample is Kate Pincus-Whitney whose work has an air of jubilant and wild abandon. Rather than tapping scenes from her home or personal life, Pincus-Whitney taps themes surrounding food, meals, and all the cultural and lifestyle contexts that come with it. Her current exhibition in Los Angeles is titled “To Live and To Dine in LA/ You Taste Like Food.” Her paintings are maximalist both in the abundance of subjects, with tables overflowing with dishes and delicacies, shown as well as in their detail: where the spread ends, colorful and amorphous patterns fill the voids. With a bombastic approach to composition and color, her work takes on an almost diaristic quality, illustrating her explorations into the world of food and its intersections with broader lived realities.

Kate Pincus-Whitney, To Live and To Dine in LA/You Taste Like Home: Meet Me at The Brown Derby (I love Lucy) (2024). Photo: Mason Kuehler. Courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles / New York.

Beyond these, there are numerous further contemporary artists whose work more broadly falls within this type of Contemporary Intimist slant, such as Robert Minervini, Nikki Maloof, Nicole Dyer, or Daniel Gordon.

One major divergence from the Intimist movement in the vein of Bonnard is the general lack of figuration, replaced instead with a sense of presence. Owing strongly to the intimate and personalized depictions of everyday tableau and displays of a personal nature, each artist’s work suggests that someone was there just a moment ago. Within historic Intimism, the inclusion of figures was more or less pervasive, as the inclusion of a spouse, child, or friend at seemingly casual moments contributed to the feeling of being allowed behind closed doors.

Hilary Pecis, Breakfast Nook (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Timothy Taylor, London / New York.

Referring to the vibrant, personal, maximalist approach found throughout these artists’ practices as simply another form of still life would be a disservice to the work, and glosses over the distinctive manner in which each artist’s paintings parallel and diverge, or the intrinsically intimacy created through the personal arrangements of objects and color choices. This reading also doesn’t offer room to the diversity of each artist’s oeuvre, which reflect the range of experiences and contexts they navigate and subsequently translate into their art.

A focus on vibrant pattern, object specificity (often acting as clues to the artist’s personality or interest) and can be identified as a codifiable style akin to movements of art historical periods past.

There are myriad interpretations as to why this trend has become observably obvious, but in a post-movement art world it suggests a pervasive attunement to the more exuberant possibilities of painting. Whether seen as an inverse reaction to the bleak state of the world or personal taste for loud aesthetics, Contemporary Intimism demonstrates what painting can be when pulling out all the stops.