Art World

A Cash Dash, Mounting Frustration, and the Rise of Online Shows: Here’s How China’s Art World Is Dealing With the Coronavirus

Some 58 million people have been barred from leaving their homes.

Some 58 million people have been barred from leaving their homes.

Vivienne Chow

For weeks, Jijie has not been able to leave his home in a village in the outskirts of Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei province in central China.

Like the rest of some 58 million people living in Hubei, the epicenter of the deadly novel coronavirus, the artist and illustrator has been barred from leaving his home during an unprecedented government lockdown as officials try to contain the virus.

Although Jijie and his housemates have stocked up on food and daily necessities, he is extremely concerned about a recent development: a family member of his has been infected with the virus.

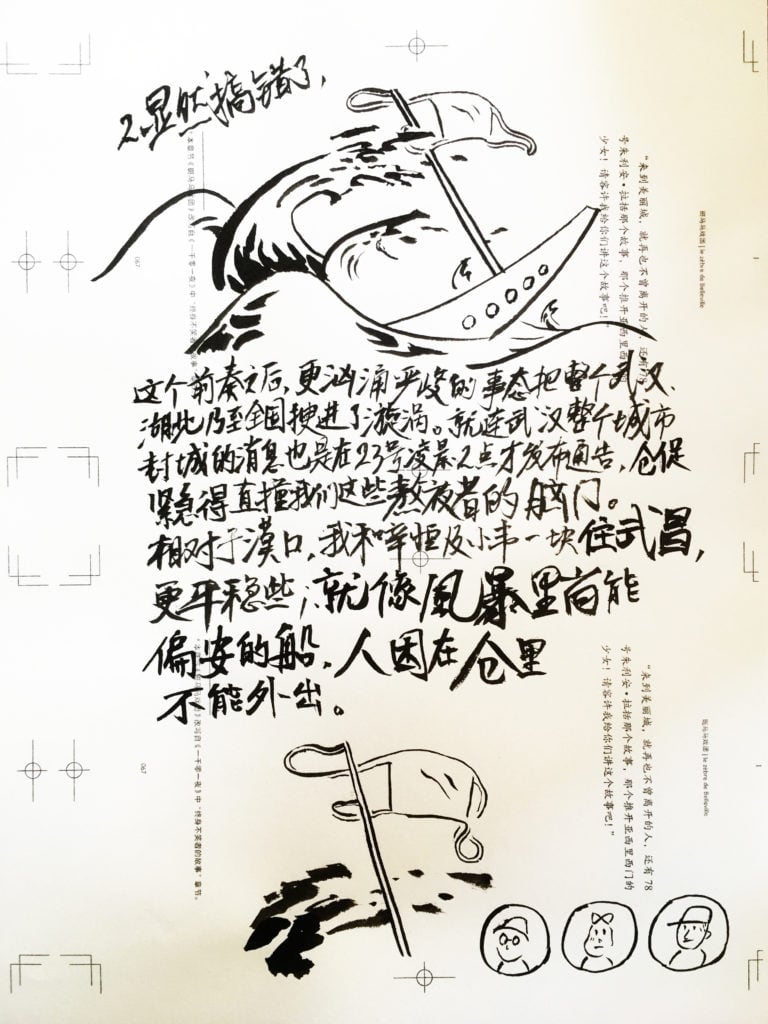

Comparing his life to one on a boat struggling to find an anchor in rough seas, Jijie is now telling his story in a series of illustrated diaries, in which friends and families, isolated in separate boats, can only wave at each other from afar.

An image from Jijie’s diary, in which he’s been recording his responses to being under lockdown in China.

“I just want to do something, to keep a record of what I have experienced,” Jijie says on the phone from Wuhan. “This helps me collect my thoughts. I think every one of us wants to keep a record, a kind of evidence, of this event.”

For most people, art is an afterthought in the face of the highly contagious COVID-19, which, in mainland China alone, has infected nearly 76,000 people and claimed more than 2,230 lives.

But for others, creating images from their experiences and posting observations on social media has been an outlet in a difficult time.

“We ask ourselves, what can art do?” says Amber Wang, director of Gallery Weekend Beijing. “It seems that art is so trivial, and that it cannot solve problems immediately. But with good intentions, we reflect and do what we do best to contribute.”

A medical staffer in Wuhan checking the body temperature of a patient who has displayed mild symptoms of the COVID-19 coronavirus. Photo by STR/AFP/China OUT via Getty Images.

Late last year, before news of the coronavirus broke, Dr Li Wenliang and seven other medical staffers were arrested in China for “spreading rumors” about the Sars-like pneumonia. And although their names were later cleared, Li contracted the virus and died on February 7.

“There are many Cassandras,” artist Xiaoshi Vivian Vivian Qin tells Artnet News, referring to the mythical Greek prophet who made true predictions that no one believed. “And yet people who know the truth do not have power.”

Isolated in her home in Guangzhou, Qin has been following developments closely. She says she feels more anxious about the novel coronavirus outbreak than she did about Sars in 2003.

As an outlet, she has been channeling her emotions into images.

One of them depicts Wuhan bridge, overlaid with an image of a letter signed by Dr Li. Another one is a touched-up picture of a red banner, which addresses virus-related discrimination against people from Wuhan. “What we can do now is keep records of what is going on,” she says.

In Wuhan, Jijie documented the events surrounding Dr Li’s death in a metaphorical way. The night that he died, Jijie made a drawing depicting a man with a whistle attached to a necklace. The man looks as if he is being thrown into the sea.

Others have made works reflecting the boredom of life under lockdown. Artist Li Nu, in a project inspired by John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Bed-In for Peace, recorded himself in his Beijing studio between January 26 and February 1. The black-and-white images depicting his mundane activities—reading, lying in bed—reflect the lonely lives of many people living under lockdown.

The Tadao Ando-designed He Art Museum will now open at a later date than originally intended. Image Courtesy of the museum.

Contingency Plans

Cultural facilities remain closed in China, delaying exhibition openings and even the unveiling of new museums, such as the He Art Museum.

Founded by He Jianfeng, the heir to the electrical-appliances manufacturer Midea, the institution was originally scheduled to open March 21. Now, that date has been pushed back to the fall.

“Here in the Shunde district, the situation is not as serious compared to other places,” says the museum’s director, Shao Shu.

“All supermarkets are still open and we can have our goods delivered. But we can’t meet the delivery guy and have to avoid direct contact. Different cities have different restrictions. Here, cars that are not registered with the city of Foshan [where Shunde is located] will need a permit to enter the city.”

But now that the opening shows have been pushed back, loans that were secured months in advance will likely have to be canceled.

Grocery stores in China and Hong Kong have become ghost towns in the wake of the coronavirus. Photo by Anthony Kwan/Getty Images.

“There will be many adjustments of the inaugural exhibition for sure, but not to the extent of recurating the show,” Shao says.

Although workers were supposed to be allowed to return to their jobs on February 10, allowing construction crews to complete the Tadao Ando-designed building, that date has also been pushed back.

But even after restrictions are lifted, tight controls will be put in place. Anyone travelling into Shunde from outside the district will have his or her health and travel history investigated, and office employees must be seated one meter apart from one another, all facing in the same direction, Shao says. Daily temperature checks and health reports will also be part of the new routine.

But Shao says the delay of the grand opening will give him more time to beef up the museum’s collection. As of last year, the museum has more than 480 pieces of modern Chinese art.

“But we want to strengthen the collection by adding more Chinese and international contemporary artworks,” he says.

The Palace Museum is now offering an online-only animated panorama of the famed site. Photo by Du Yang/China News Service/Visual China Group via Getty Images.

Meanwhile, organizers of Gallery Weekend Beijing are still moving forward, even following the cancellation of the Jingart art fair, which was scheduled to take place in Beijing in May.

“Despite the challenges of the circumstances, we have not stopped our work,” says the event’s director, Amber Wang. “We do what we can by maintaining our voices, and we are still preparing for the event, aiming for April.”

Wang says she and her colleagues are working from home and are posting on WeChat, China’s all-in-one social-media app, to maintain public interest in the show.

Indeed, the internet has become a prime source of cultural exchange since the government tasked museums with putting their exhibitions online while their doors remained closed.

The Long Museum, for example, is presenting images from the 25 exhibitions it staged last year on WeChat, including photos of artworks and explanatory texts.

The museum’s founder, mega-collector Liu Yiqian, has also donated 30 million yuan ($4.27 million) to the Hubei Charity Federation and his company, Guohua Life Insurance, has donated another 200,000 yuan ($28,471) in life insurance coverage to each front-line medical staffer in Hubei Province.

The salesroom at China Guardian Auction House.

Institutions like the How Art Museum in Shanghai, meanwhile, are hosting charity auctions to support victims of the coronavirus. The museum has donated 30 artworks, worth 1 million yuan ($142,359) total, as the first items in a sale for which the public is being asked to donate more objects.

Auctions houses are also holding their own similar events. Although China Guardian has postponed its Hong Kong spring auctions, scheduled to begin early April, it will host online charity sales on March 9 and 10.

According to Hu Yanyan, the company’s president, the auction house has donated 1 million yuan ($142,359) and secured 113 works that are expected to raise more than 5 million yuan ($711,875) to help frontline medical workers and their families.

Hu says that, although the epidemic has caused a great deal of disruption, it could, on a positive note, drive the development of the digital new economy.

“But it will be a long time before online sales could replace traditional auctions or transactions of art,” she says via email. “It is very difficult for the top level of the art market to rely solely on virtual transactions.”

Nevertheless, the Beijing Association of Auctioneers is urging individual auction houses to develop their own online sales platforms “to not only adapt to the new consumer behavior or expand business, but also to minimize risks brought by unpredictable circumstances, such as this virus outbreak.”

But China’s art market, Hu says, is expected to undergo extensive adjustments even after the coronavirus outbreak is over.

“This epidemic is more severe than any adversity we have experienced. Our lives have been put on pause,” she says. “When normality resumes, the recovery of the art market might be slightly slower than other sectors.”