On View

How Native American Artists are Combatting Misrepresention with ‘Indigenous Joy’

The exhibition “American Sunrise: Indigenous Art at Crystal Bridges" foregrounds "Indigeneous joy," according to curator Jordan Poorman Cocker.

The exhibition “American Sunrise: Indigenous Art at Crystal Bridges" foregrounds "Indigeneous joy," according to curator Jordan Poorman Cocker.

Adam Schrader

The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art highlights its latest acquisitions of works by Native American artists in a new exhibition celebrating the intergenerational expressions of Indigenous artists through historical and contemporary art.

Artist-curator Jordan Poorman Cocker co-curated “American Sunrise: Indigenous Art at Crystal Bridges” with Ashley Holland, director of curatorial affairs at the Art Bridges Foundation. The latest acquisitions came from direct talks with the artists as well as from Native American markets and through art galleries, said Cocker, who also serves as the museum’s officer for compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGRPA).

Ryan RedCorn, Raymond RedCorn (2018-2023). Courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Among the new acquisitions is a photograph by the Osage artist Ryan RedCorn which depicts the late fashion designer Ardina Revard Moore, who founded the Indian apparel business Buffalo Sun. Moore, who was also one of the last remaining speakers of the Quapaw language, is pictured holding a young baby named Hikele Byrd.

“In Redcorn’s portrait, generations, legacy, resilience, and the importance of family is highlighted in monumental scale,” Cocker said, highlighting the RedCorn work as one in the exhibition that best represents the thematic aspect of kinship.

Cocker herself is an Indigenous artist from the Kiowa Tribe and from the Kingdom of Tonga in the Polynesia region of the Pacific. Her artistic and scholarly work seeks to promote Indigenous knowledge and creativity.

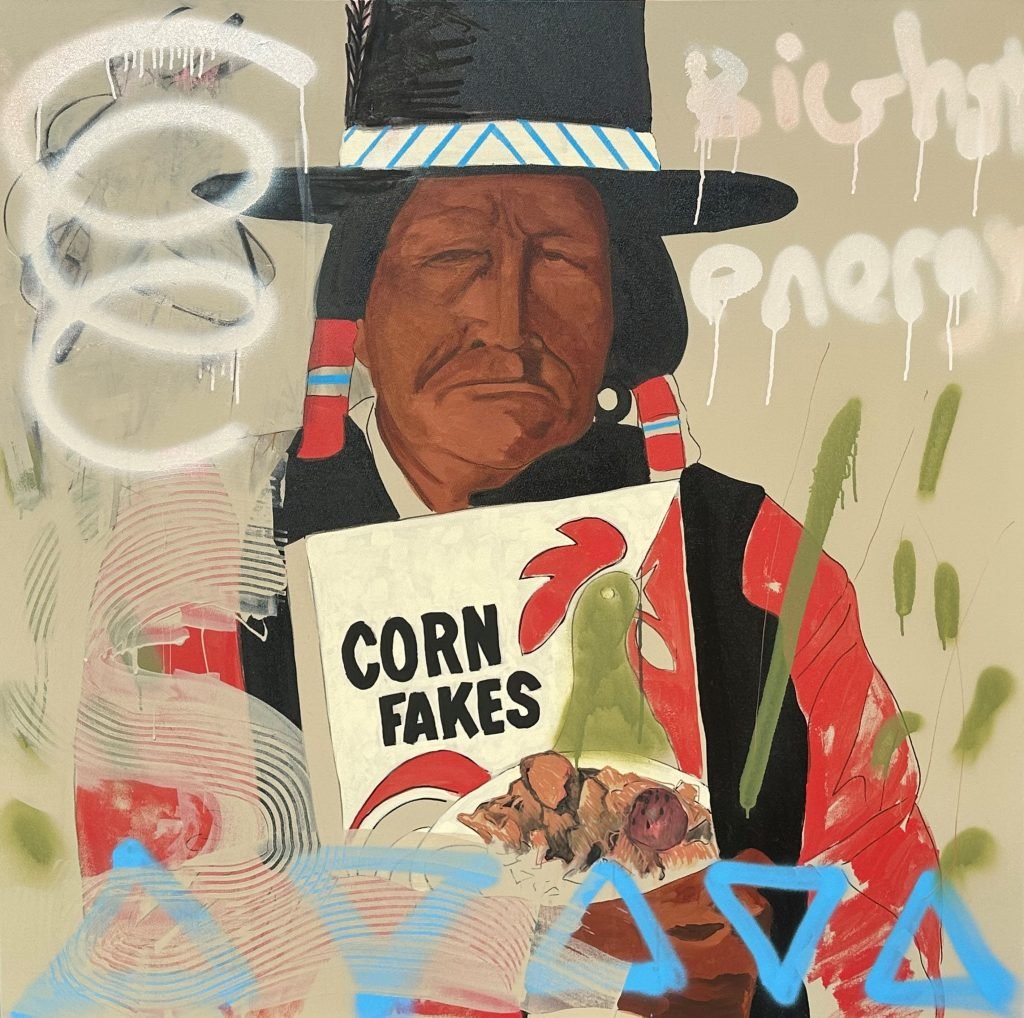

Frank Buffalo Hyde, Big Hat Energy (2023). Courtesy of Frank Buffalo Hyde/Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

“Misrepresentation and underrepresentation of Indigenous-led stories and narratives has historically led to an over-representation of stereotypical imagery and propaganda within museums due to settler colonialism,” Cocker said. “When museums support Indigenous curators to work closely with artists and communities to tell our own stories in our own ways, museums move closer toward best practice.”

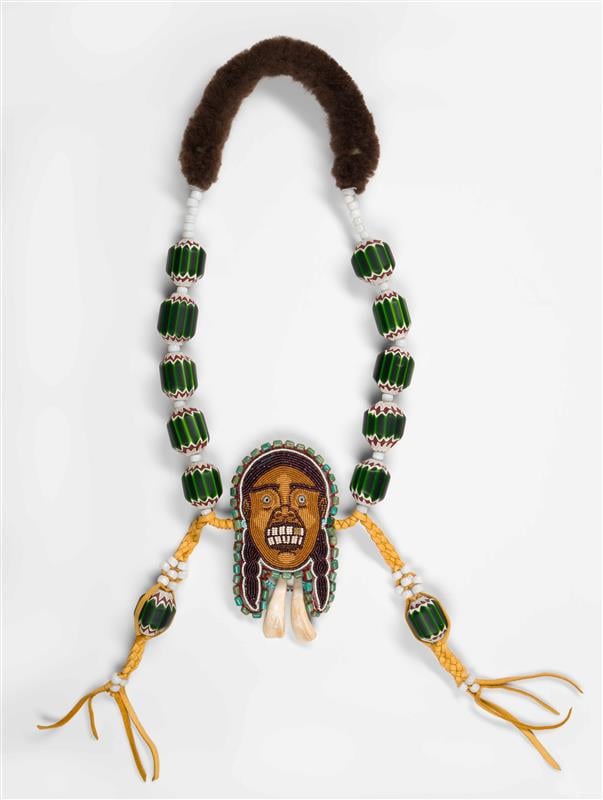

The new acquisitions also include, among other pieces, a characteristic punching-bag sculpture by Jeffrey Gibson, a mixed media work by Ojibwe artist Andrea Carlson, a painting by Onondaga and Niimíipuu artist Frank Buffalo Hyde inspired by a 1962 advertisement for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes cereal, and a beaded necklace by the artist Bobby Dues called IHS Dental Plan (2024) that Cocker described as “fabulous.”

Bobby “Dues” Wilson, IHS Dental Plan (2024). Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

That work is accompanied by a projection of a video titled Smiling Indians by Redcorn and Sterlin Harjo.

“The throughline between both works is Indigenous joy, happiness, and imagery of smiling Indigenous people which is rarely shown in the museums and the media,” Cocker said. “This pairing and other works in the exhibit upend negative and inaccurate stereotypes of Native American people.”

Cocker also praised the work The Zenith by artist Cara Romero, who is slated to have her first solo show at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire, in January. That work, a photograph, features a person with a spaceflight helmet on in outer space while surrounded by floating cobs of corn. To Cocker, it highlights the show’s theme of Indigenous Futurism. Meanwhile, Kelly Church’s Sustaining Traditions into the Future was selected by Cocker as the best example of the theme of place.

Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, Home of the Brave (2013). Courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

The exhibition features six new commissions by Church, Jeri RedCorn, Jane Osti, and Roy Boney that have never been seen by the public. In total, more than 30 artists spanning more than 150 years of artmaking are featured.

“American Sunrise: Indigenous Art at Crystal Bridges” is on view through March 23, 2025 at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 600 Museum Way, Bentonville, Arkansas.