Art World

Why Cyprus Is Europe’s Most Exciting Art Hub Right Now

Artist-run spaces abound as many return to the Mediterranean island from stints abroad.

Artist-run spaces abound as many return to the Mediterranean island from stints abroad.

Cathryn Drake

There is movement afoot in the art world, triggered by the rising scale of the art market coupled with the downturn in Western economies, from the cultural capitals to places on the margins where physical space is more affordable and mental space more expansive.

Dropping out is not the risk it used to be: While the conditions in major cities have become prohibitive to creative production and the stakes higher, art producers and dealers have become nomadic, even shedding gallery spaces, to chase increasingly interesting marginal markets around the globe.

In turn, art production is becoming less object-oriented and artists hop from residency to residency, making it easier to participate from the periphery.

Located at the southern terminus of the European Union, Cyprus is both isolated and yet highly contested for its strategic proximity to three continents as well as offshore oil and gas resources. The heart of the capital, Nicosia, is split down the middle by barbed wire—a formerly lively market street and the international airport left bereft in the UN buffer zone—the scar of a political stalemate between Turkey and Greece. The threat of conflict is escalating even now as hard-line Turkish president Recep Erdoğan ramps up nationalist rhetoric. The cancellation of Manifesta 6, planned for Nicosia in 2006, attests to the complex nature of the Cypriot reality.

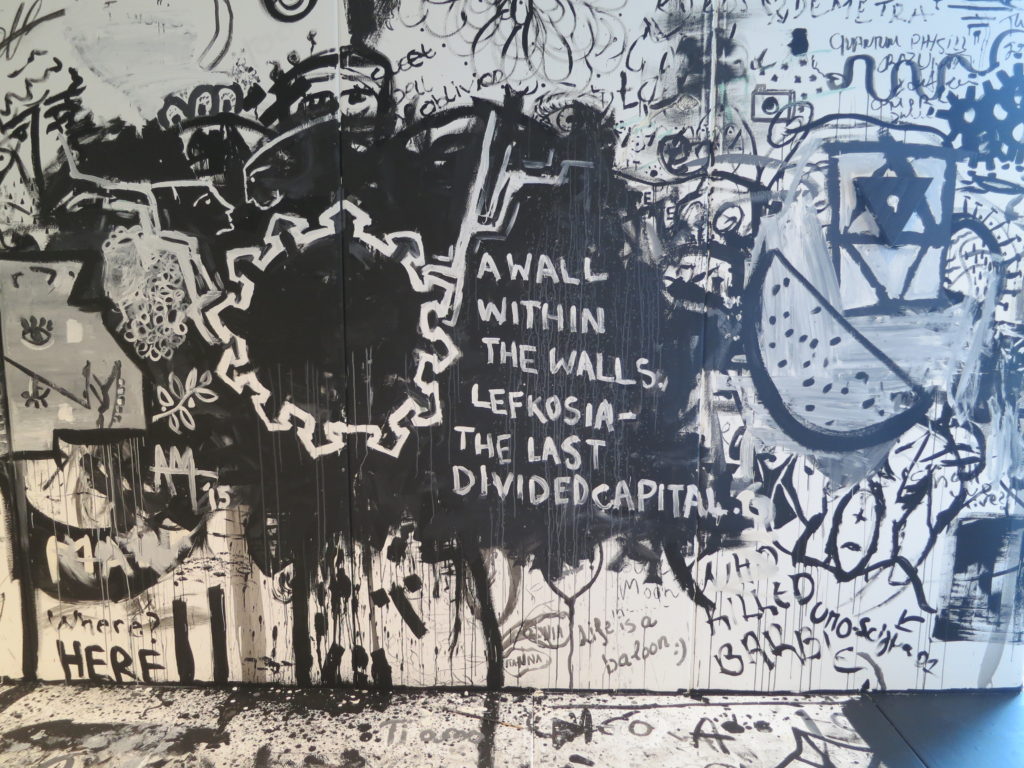

Aristides Mettas, Last divided capital (detail) (2015) at Leventis Center. Photo by Cathryn Drake

So living on the edge is nothing new to Cypriot artists, and a young contingent has returned from studies abroad to collaborate in getting one another’s work out there by opening collective project spaces.

The art market has always been elusive in Cyprus, and the few influential commercial galleries that were active—like Archimede Staffolini, directed by Pavlina Paraskevaidou, and Omikron, backed by collector Nicos Pattichis—did not survive the economic crisis, the latter closing in 2012.

Staffolini showed now successful artists such as Haris Epaminonda and Polys Peslikas early on; Omikron’s 2010 group show “Notes to Self,” curated by Elena Parpa, introduced a new generation of Cypriot artists who grew up in the digital age.

Maria Stathi at Art Seen. Courtesy of Art Seen, Nicosia.

A year after Omikron closed, former director Maria Stathi, previously at London’s Anthony Reynolds, opened the nonprofit space Art Seen in Nicosia, which produces limited-edition prints and multiples to support its exhibition program.

The production of affordable art supports the exhibition program and is part of an attempt to reach out to a nontraditional audience. “It is super challenging to work in Cyprus,” she says. “There are not that many people who understand what we are doing and why we are doing it.” Aside from a dearth of contemporary art spaces, there was no fine-arts degree program until very recently.

Similarly, Point Centre for Contemporary Art, established by Andre Zivanari as a not-for-profit space in 2012—following on a program supporting Cypriot artists for the Künstlerhaus Bethanien residency—commissions original work from artists for solo exhibitions. The recent show, “Completely Something Else,” curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, brought together a mix of foreign and Cypriot artists, including Epaminonda, Phanos Kyriacou, and Christodoulos Panayiotou, to convey how relationships between physical objects, repeated and juxtaposed, generate new and universal meanings in different contexts, often as shadows of other places and times. Artists Victor Costales, Julia Rometti, and Maria Loboda stayed for more than a month to explore what they perceived as the island’s “charged landscape,” highlighting how space is constructed through experience, memory, and history.

Phanos Kyriacou’s upcoming exhibition there, “Exhaustion,” will comprise an installation of 36 drawings and a small sculpture in an attempt to evoke the tension between representation and reality through the repetitive depiction of an object, its planes accumulating finally to suggest its form but not its substance.

In fact, Kyriacou’s now-defunct project space Midget Factory (2003-12) anticipated the current proliferation of artist-run spaces, many of which alternate as sort of open studios: located in the red-light district of Nicosia’s old town, it was “open” 24/7 through the use of movement-detection lights and attained a cult following by the time of its demise, when the building was finally demolished. Other precedents were Stoa Aeschylou, directed by Demetris Neokleous and Panikos Tembriotis, and Apotheke, run by Demetris Taliotis in a post-industrial space in the city center until 2012. A multidisciplinary node for innovative happenings, it nurtured a network for many of the young artists practicing now, including Kyriacou, Maria Toumazou, and the director’s brother, Constantinos Taliotis.

Artist Polys Peslikas working on Venice show

Artist Polys Peslikas, who will represent Cyprus in the 57th Venice Biennale, started a space called Volks two years ago in a decommissioned garage. The owner offered it to him as a place to launch large-scale work, and he decided to hand over the keys to a series of artists. “Coming from a small colony of artists, it’s very important to have this group idea and to connect with people and to share experiences and information,” he says. “Before this we just curated or invited each other to do shows.” The space has since been sold, so the art program will conclude in a few months.

“It’s something that is natural to happen on the periphery; if you don’t have a market or someone to support you, you have to create things in order to exist,” Peslikas says. “From time to time it appears and disappears. It did not happen in the nineties because of the prosperity.”

This way of working together seems to follow a local lineage. Nicosia Municipal Art Center’s recent retrospective “Glyn Hughes: 1931-2014,” curated by director Yiannis Toumazis, shed light on the role of the Welsh artist, educator, and writer in igniting a community in Cyprus’s cultural scene. Taking up residence shortly before the island gained independence from Britain, he and artist Christoforos Savva, just returned home from Paris, established the seminal Apophasis Gallery in the latter’s home in 1960, organizing lectures, concerts, happenings, and readings as well as exhibitions.

Peslikas is replicating the tradition in his Venice Biennale pavilion, “The Future of Color,” by inviting other artists to contribute, including the collective Neoterismoi Toumazou, who opened a project space in Nicosia in 2015.

Maria Toumazou, Orestis Lazouras, Marina Xenofontos of Neoterismoi Toumazou. Photo by Eleni Papadopoulou

Returning from studies in the United Kingdom, the collective’s Orestis Lazouras, Marina Xenofontos, and Maria Toumazou took over a clothing shop formerly operated by the latter’s grandfather, installing a series of window projects between 2011-2013, with the last one staged by Luís Lázaro Matos before moving out the old stock. After renovating the space, they mounted “Karat Castle,” an exhibition of fantastic sculptural works by Xenofontos about recalibrating normative perception.

Their cheeky Neo Toum fashion line, which started with a design for a Glasgow football club scarf, helps with expenses. “The spaces are communal somehow,” Toumazou says. “We also wanted to provide an opportunity for our friends from abroad to show here.” She will get her turn in the solo show “The End of the Story,” opening on April 1.

Peter Eramian & Stelios Kallinikou at Thkio Ppalies. Photo by Panagiotis Mina

Thkio Ppalies (“chop-chop” in local lingo) was inaugurated in spring 2015 by photographer Stelios Kallinikou and artist Peter Eramian, formerly a contributor to Naked Punch and publisher of the magazine Shoppinghour in London, and The Cyprus Dossier in Cyprus, to host exhibitions and experimental sound projects in an erstwhile auto-repair garage.

For her exhibition “Solid Plans” there last autumn, Natalie Yiaxi rendered household objects into their surreal alter egos in clay to disrupt habitual perception of everyday life. Yiaxi and artist Maria Loizidou also direct the visual artist association, EI.KA, which serves as a union and organizes exhibitions in a former greenhouse, called Phytorio (“Nursery”), in the Nicosia Municipal Garden.

Artists Maria Loizidou and Natalie Yiaxi at Phytorio

It’s a tightly-knit scene and the artists running the spaces invite each other to do shows (often collaborating in romantic partnerships too). “It’s a new phenomenon—the first time we have a real creative community in Cyprus—and it’s great that artists can experiment and support each other,” Zivanari says. “Rent is not as expensive as before, and the government is providing more funding for the arts.”

And there’s no lack of empty space to fill with art: In February artists Andreas Z. Mallouris and Theodoulos Polyviou inaugurated Koraї Project Space with “Four Words on Desire,” an ensemble of poetic works by Polyviou that incorporate liminal space.

Lia Haraki at Performance Shop

In 2014, artist Lia Haraki opened the pop-up Performance Shop as part of the Pop-up Festival initiated by NiMAC to fill retail stores, including an entire shopping mall left empty in downtown Nicosia, with projects by artists, performers, and designers. The following year she set up for a few months in a storefront retail space in Limassol, where people paid to participate in interactive performances such as “Active Spectator.” It provides a new way for Haraki to support herself as a performance artist as well as an answer to the question “How can performance be made more accessible and relevant for the local community?”

Last autumn artist Maria Lianou and architect Alexandros Christophinis organized an exhibition of site-specific artwork, “Limassol: The Aftermath of Development,” in an abandoned public housing complex along with lectures, visualization workshops, and architectural tours. They followed up with a book documenting the city’s historic buildings to raise awareness about the fate of architectural heritage in the quest for modernity—and the opportunity the financial crisis provides to reconsider the urban plan and encourage participation.

Alexandros Christophinis and Maria Lianou

Other multidisciplinary artist groups cross-pollinating the landscape without fixed spaces are Re-Aphrodite (led by Evanthia Tselika and Chrystalleni Loizidou), and Pick Nick, comprised of architect Alkis Hadjiandreou, artist Panayiotis Michael, and writer Maria Petrides.

“In the last decade artists have migrated back to Cyprus after being exposed to different ways of working and being an artist, and that’s challenged them,” Petrides says.

Experimentation is a prerogative at the periphery, and in that sense the lack of a market may actually be a boon. Making art under these circumstances is an inspired act of survival and resistance, and young Cypriot artists are defining the moment.