Art & Exhibitions

Dalí’s Rare Watercolors Resurface in an Immersive Show—Save for One Long-Lost Piece

Five watercolors were created for a notorious opera, but one never made it to the museum where the others reside.

“Dalí Alive,” a multimedia exhibition at the Lume at Indianapolis’s Newfields, has redirected attention to a mysterious case of a missing watercolor by the famed Surrealist whose designs the show is devoted to.

The exhibition, spread across 30,000 square feet, sees Salvador Dalí artworks enlarged and projected onto the walls and floors, promising an immersive experience. “Dalí Alive” follows on from the Lume’s first two immersive shows devoted to reliable crowd-pleasers, one each to Impressionism and to Vincent van Gogh.

The display includes four Dalí watercolors (remember that number!) from the collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, part of the Newfields complex.

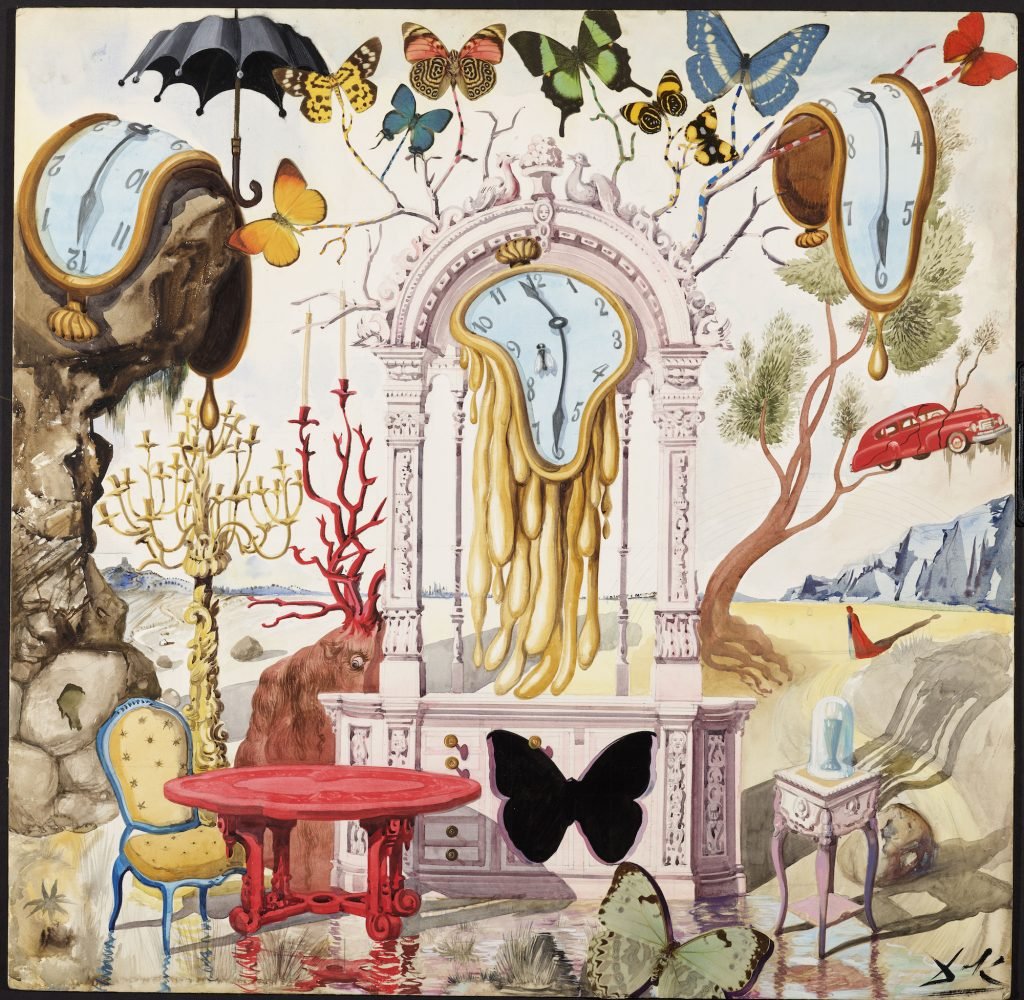

Salvador Dalí, Tragedy and Comedy (1961). © 2023 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

The Spaniard created the watercolors as part of his commission to design sets and costumes for the 1961–62 production of Baroque composer Alessandro Scarlatti’s 1714 opera The Spanish Lady and the Roman Cavalier, produced by Lorenzo Alvary. A Hungarian-American operatic bass, Alvary created his own company in order to put on the opera, in which he played the male lead.

Dalí was in some ways a sensible choice: he had already some experience as a designer for theatrical productions, including several ballets throughout the 1940s.

The opera follows a love story between a Roman centurion and a Catalan woman following the fall of the Roman Empire. The production traveled to Venice, Brussels, and Paris, a tour apparently so physically grueling that a principal ballerina (who had been performing without an understudy for seven months) collapsed on stage during a Paris performance.

Salvador Dalí, The Elephants (1961). © 2023 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Decca Records released a 1962 record of the opera that featured an interview with Dalí. The album cover features one of the watercolors, Apotheosis (1961), emblazoned with a large signature; other Dalí works are included on the reverse and inside of the record sleeve, including Tragedy and Comedy.

In addition to Apotheosis, which features Dalí’s trademark melting clocks among other Surrealist details, and Tragedy and Comedy, Lume is also displaying Musicians and The Elephants, which which Dalí created for the opera and which stars long-legged pachyderms that are also seen in Dalí’s 1948 The Elephants.

Dalí had extravagant plans for The Spanish Lady. Actors blew bubbles filled with Guerlain perfume (though they failed to achieve the square bubbles that Dalí wanted). A Time magazine review of the show gives a long list of things that went awry during a performance at Venice’s La Fenice theatre. These oddities included Dalí himself throwing paint onto a canvas (and onto some audience members) while dressed as a Venetian gondolier, and several “visual distractions” like a walking violin, a blind man seated in front of a TV, some uncomfortably erotic dancing, and liquid carbon dioxide “milk” flowing onto the stage from underneath the rafters.

Salvador Dalí, Musicians (1961). © 2023 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

The collaboration between artist and producer was not a peaceful one. Dalí took Alvary to court when he claimed that he was not staying true to his creative vision. (The case was dismissed.) Plans to take the show to London and New York were duly scrapped.

“Dalí Alive” is the first time the watercolor set designs from The Spanish Lady have been on public display for over 45 years. Alvary and his wife Hallie, who owned the paintings, donated them to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 1973; their agreement with Dalí stipulated that they would not be allowed to sell them.

But here’s the mystery: there were five watercolors, not just the four on view in Indianapolis. The location of the final watercolor is unknown, and it was not donated to the IMA.

Also missing are the costume designs. Their whereabouts are entirely unknown.

“Dalí Alive” is on view at the Lume Indianapolis at Newfields, 4000 N Michigan Rd, Indianapolis, through December 29.