“Dalí/ Duchamp” is a curiosity, exploring the friendship and chains of influence between what, to contemporary eyes, seems an unlikely pairing. The senior by 17 years, Marcel Duchamp met Salvador Dalí through the surrealist group in Paris in the early 1930s, and the pair remained close until the French artist’s death in 1968. Photographs show them holidaying together in Cadaqués in the 1930s: Dalí flamboyant as ever, mugging for the camera in a patterned beach robe; Duchamp quiet, pale, smiling. They look like they’re having fun.

Both artists are, in their own way, the victims of a posthumous cult of personality. We think of Dalí the showman, the egotist, covering himself in glue and goat excrement to woo Gala, and staging stunts for the press. His art is familiar from dorm-room posters: fellow travellers in undergrad experiments with hallucinogens. Duchamp is the quiet chess player, the intellectual, the innovator, the thinker, and slow maker. Dalí painted in oils, delicately, and with experiments in perspective that link back to the Spanish Renaissance. Duchamp, as the cliché goes, was the forward-looking “father of conceptual art.”

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel (1913, 6th version 1964). Photo ©Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada / ©Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017.

Duchamp shaped the way art was made and discussed in the latter half of the twentieth century. But so, too, alas, did Dalí, with his ability to sign 1,800 blank sheets of paper an hour, his scandals, his business plans, and his courting of notoriety.

This modestly sized show—extending to three galleries and two smaller rooms—attempts to re-complicate our readings of both artists, and to tease out alliances within their work. This it does most successfully in a section on sex and the human body, subjects that fascinated both artists. These are by no means exceptional interests within the wider context of surrealism: both Duchamp and Dalí showed in the 1938 “Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme,” where representations of the body in general, and the mannequin in particular, provided major themes.

Recent exhibitions in both London and Philadelphia have seen Duchamp’s work presented within his later New York milieu, alongside John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. Placing his work in an earlier European context gives things a rather different complexion.

Marcel Duchamp, The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (verso with Paradise: Adam and Eve) (1912). Philadelphia Museum of Art ©Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017.

Dalí’s erotic sketches reveal a fascination with urination. He depicts women as both saint and sex object. An illustrated text describes a beach visit with Duchamp and Gala, during which he ducked behind a rock to urinate and found himself overcome by the sight of his wife next to his sunburnt friend and the smell of grilling cutlets. He remained crouched out of sight, sucking on the rock and masturbating as he watched them. The fleshy mountains of his paintings betoken a worldview in which there are no clearly defined limits between the sexual, sentient body and the ordinarily unyielding forms of the surrounding landscape.

Duchamp’s Fountain (1917)—or at least the 16 reproductions of the work sanctioned by the artist in 1964—is now familiar almost to the point of banality. Looking beyond its revolutionary status as a readymade, it is as perverse as anything presented us by Dalí: a receptacle for male urine that could be seen as suggestive of a female sex organ. Some 40 years later, Duchamp made a series of “erotic objects” including Wedge of Chastity and Female Fig Leaf, which follow a fleshy theme of slits and wedges. Etant Donnés, Duchamp’s final work, permanently installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is, for all of its technical sophistication, still a headless woman with her legs apart.

Marcel Duchamp (reconstruction By Richard Hamilton), The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915 (1965-6 and 1985).Tate: Presented by William N. Copley through the American Federation of Arts 1975 Photo ©Tate, London, 2017 / ©Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017.

A lovingly produced study for Etant Donnés, modelled in leather and velvet, is shown here, alongside photographs supplied by Dalí for Duchamp as studies for the landscape. The curators suggest that Dalí was one of the few people with whom Duchamp discussed the piece, produced in secret during his supposed retirement from art making. Presented within the context of Dalí and Duchamp’s relative sexual preoccupations, this revelation seems perhaps less surprising than it might have done.

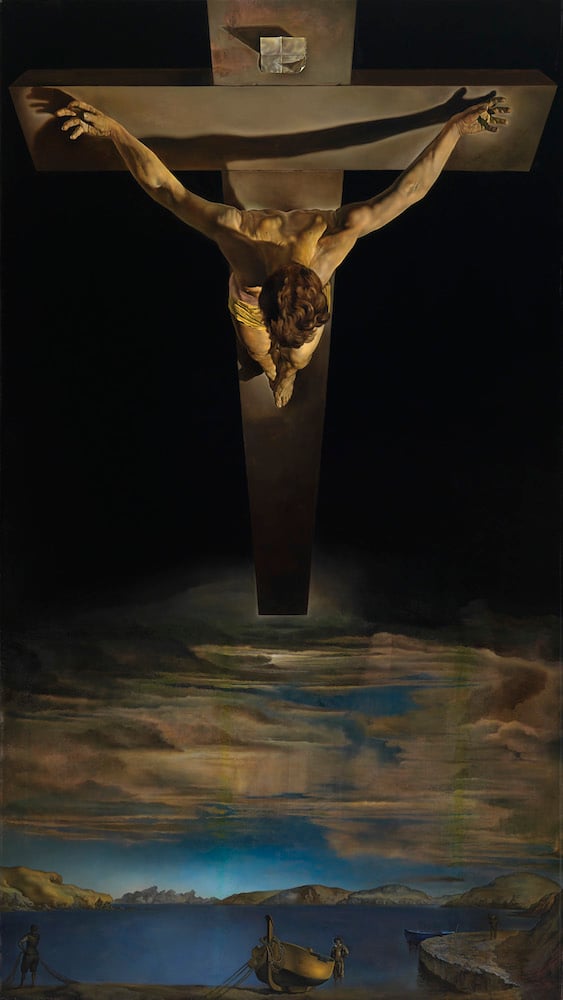

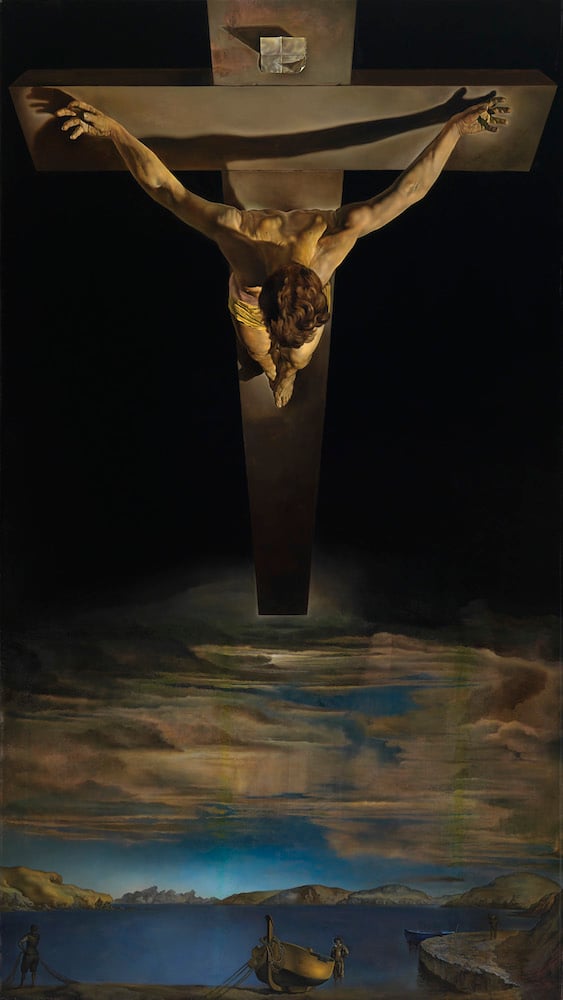

The show pushes parallels between Duchamp’s “altarpiece” The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915/1965-6/1985) and Dalí’s floating Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951): the “bride” and Christ occupying similar positions in the divided pictorial space. The curators note that the Spanish artist’s interest in religious imagery saw him estranged by André Breton and the Surrealists. Both men were passionate chess players, and were fascinated by the idea of a set of symbolic objects embodying fixed systems of behaviour and movement.

Salvador Dalí, Christ of Saint John of the Cross (c. 1951). Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow. ©CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection.

Represented here by a few dozen non production-line works—among them personal sketches and early experiments somewhat in the fauvist and cubist styles—Dalí comes out of this exhibition rather well. We do not see the Salvador of the later years, beset by scandal and far descended into self-parody. Instead, he appears as a profoundly troubled man, a loyal friend, and, certainly in his early career, an artist keen to push and experiment: Fishermen in the Sun (1928) and an almost blank work (Untitled) with geometric forms around the margins from the same year were both unexpected treats.

Despite the inclusion of a few great pieces by Duchamp—The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912), and later recreations of 3 Standard Stoppages (1913/64) and The Bride Stripped Bare—there’s a lot of marginalia and documentation. “Dalí/Duchamp”’s achievement is in rehabilitating the reputation of the former, though perhaps rather at the expense of the latter.

“Dalí/Duchamp” is on view at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from October 7 to January 3.