On View

Dancer Alvin Ailey Comes Into Full Focus in Stunning, Genre-Blurring Whitney Show

The pioneering choreographer's work being celebrated via performances, music, videos, and a plethora of contemporary art.

The pioneering choreographer's work being celebrated via performances, music, videos, and a plethora of contemporary art.

Eileen Kinsella

A deep dive into the life and career of a dancer and choreographer might not seem like a natural fit for the Whitney Museum, but it turns out that its new exhibition on Alvin Ailey (1931–89), “Edges of Ailey,” feels perfectly at home at the New York institution.

The stunning multimedia show, which has taken over the Whitney’s entire fourth floor, is an immersive feast that seamlessly presents video, music, contemporary art, and archival material against eye-catching, sumptuous red walls. Six years in the making, it was put together in collaboration with the Alvin Ailey Foundation by Adrienne Edwards, a senior curator at the Whitney, who has skillfully blended together the mediums on view.

Ailey was born in segregated Texas at the height of the Great Depression; his father left when he was three months old. He and his mother worked in cotton fields and as servants in white households before moving to Los Angeles; he later decamped for San Francisco, then New York.

Throughout his career, Ailey engaged with questions about race, sexuality, and identity, using dance to elevate and celebrate the experience of Black people in America. “Edges of Ailey” charts Ailey’s life and legacy, using a wide variety of art and music to contextualize his achievements. The Whitney’s director, Scott Rothkopf, called it “one of the most glorious exhibitions in the history of this museum” at the opening-day press conference.

“I’ve been asked a number of times: Why is the Whitney doing an Alvin Ailey show?,” Rothkopf said. “And the short answer to that question is we believe Ailey is one of the greatest artistic geniuses of the 20th century, not just in dance but in any medium.”

“To me, Alvin Ailey’s work is everything,” he said later. “It touches on his celebration and exploration of the Black experience, from his time growing up in Texas in the South, to L.A. to Broadway, to Soul Train to the White House, to dancing all around the world . . . and sadly at the end of his life, to the AIDS crisis.”

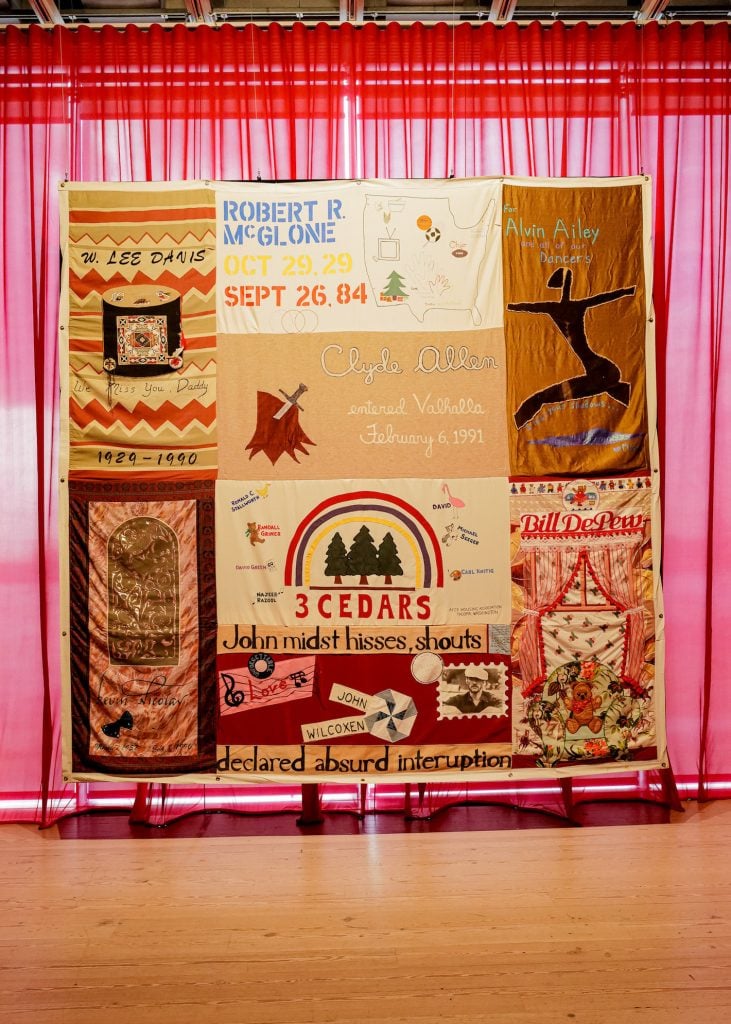

Installation view of “Edges of Ailey” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Anonymous, AIDS Memorial Quilt with Alvin Ailey panel, 1987. Photograph by Jason Lowrie/BFA.com. © BFA 2024. “Edges of Ailey” is part of the National AIDS Memorial’s efforts to bring the Quilt to communities across the United States to raise greater awareness and education about HIV/AIDS and to remember those lost to the pandemic.

Edwards said at the press conference that organizing the show was “a journey,” and involved not just the Ailey Foundation but also the Kansas City-based Allan Gray Family Personal Papers of Alvin Ailey. (The dancer entrusted his papers to Gray, a longtime friend, before he died at the age of 58. He’s now chairman of the Allan Gray Alvin Ailey Archives Family Foundation.)

The press preview had a feeling of a family reunion, with Gray present, as well as Sylvia Waters, whom Ailey asked to found his second dance company in 1974, and Bennett Rink, who’s the executive director of Ailey today.

The show has a fluid, open floor plan that invites exploration rather than prescribing a single path. Edwards described the layout as “a series of islands, an archipelago in the sense of visual connectivity” that includes 18 projectors that offer a montage of dance and music from over 200 videos.

Installation view of “Edges of Ailey” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Knave Made Manifest, 2024. Photograph by Jason Lowrie/BFA.com. © BFA 2024

“You could take an experience of the show that is really just looking at the archival material,” Edwards said. “Or you could just start over and have a visual art experience, or watch video, or meander through all of it.”

Visual art fans have plenty to enjoy. There are works on display by 82 artists, many of them active during Ailey’s life, like Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, and Alma Thomas. Four artists made work specifically for the exhibition: Lynette Yiadem-Boake, Karon Davis, Jennifer Packer, and Mickalene Thomas.

One of the earliest artworks, from 1851, is Robert Duncanson’s View of Cincinnati, Ohio from Covington, Kentucky. “The question of freedom and liberation in connection to Blackness and Queerness” was an important one for Ailey, who was born in the segregated South, Edwards said. “One of the ways we foreground that” is with this work, with a view that “at that time depending on where you stood [determined] if you were free or not.”

Rashid Johnson’s Anxious Men (2016) is juxtaposed with a notebook in which a distressed Ailey wrote in 1980, “nervous breakdown, hospitalized seven weeks.”

Installation view of “Edges of Ailey” at the Whitney Museum. Photo by Eileen Kinsella.

The show has a robust dance and performance schedule, too, which Edwards described as “Uptown comes Downtown,” with the Ailey dance company in residence at the museum for one week each month during the exhibition, which runs through February 9, 2025. (A full list of performances is available here.)

“To the best of my knowledge, no art museum has ever before organized such a deeply researched, extensively programmed, or comprehensive exhibition, about the life and work of a performing artist,” Edwards said. “I’m proud that the exhibition will include all aspects of Ailey.”

Installation view of “Edges of Ailey” at the Whitney Museum. Photo by Eileen Kinsella.

“Edges of Ailey” is on view at the Whitney Museum through February 9, 2025.