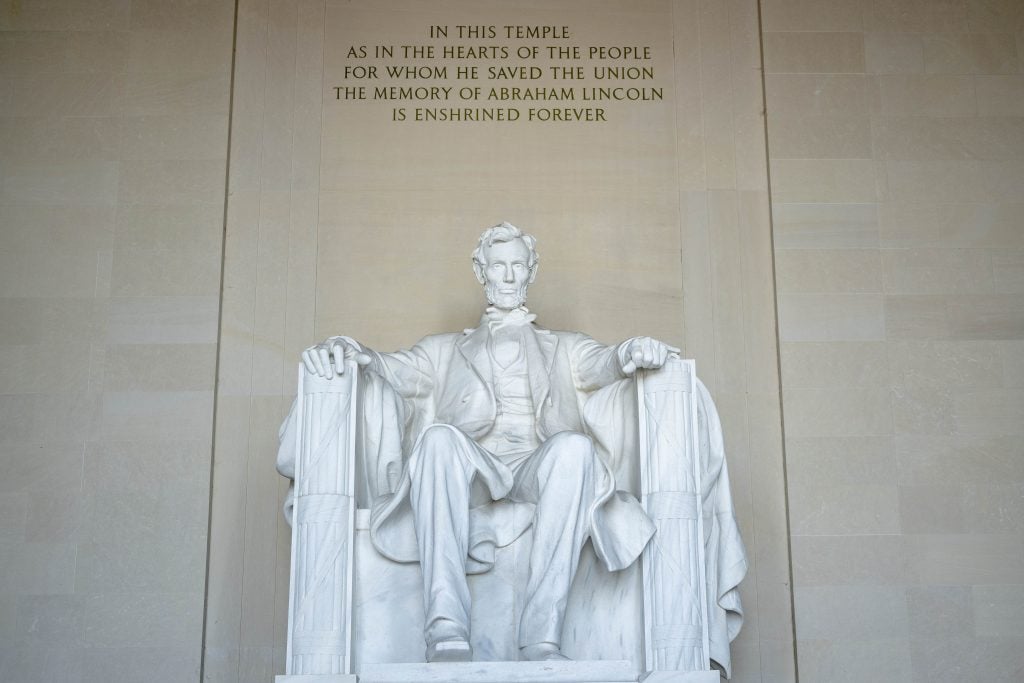

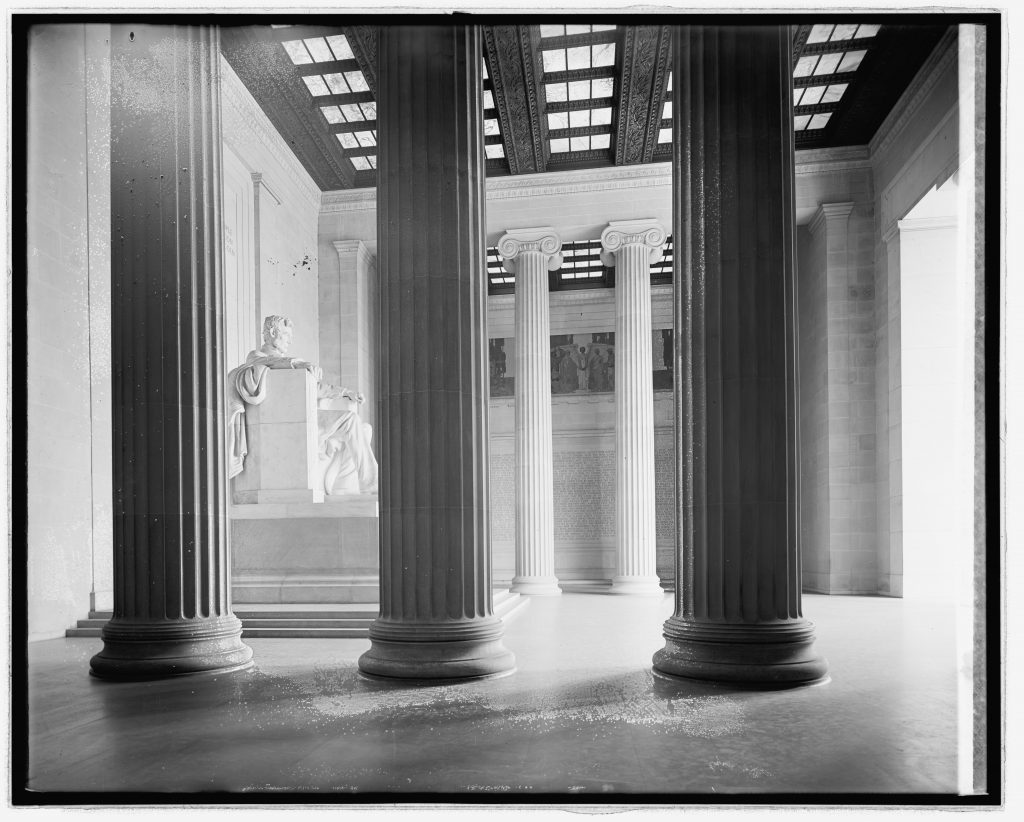

You may not know the name Daniel Chester French, but you absolutely know his work. The American Renaissance sculptor designed Abraham Lincoln, the larger-than-life seated statue at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., as well as other monuments across the U.S.

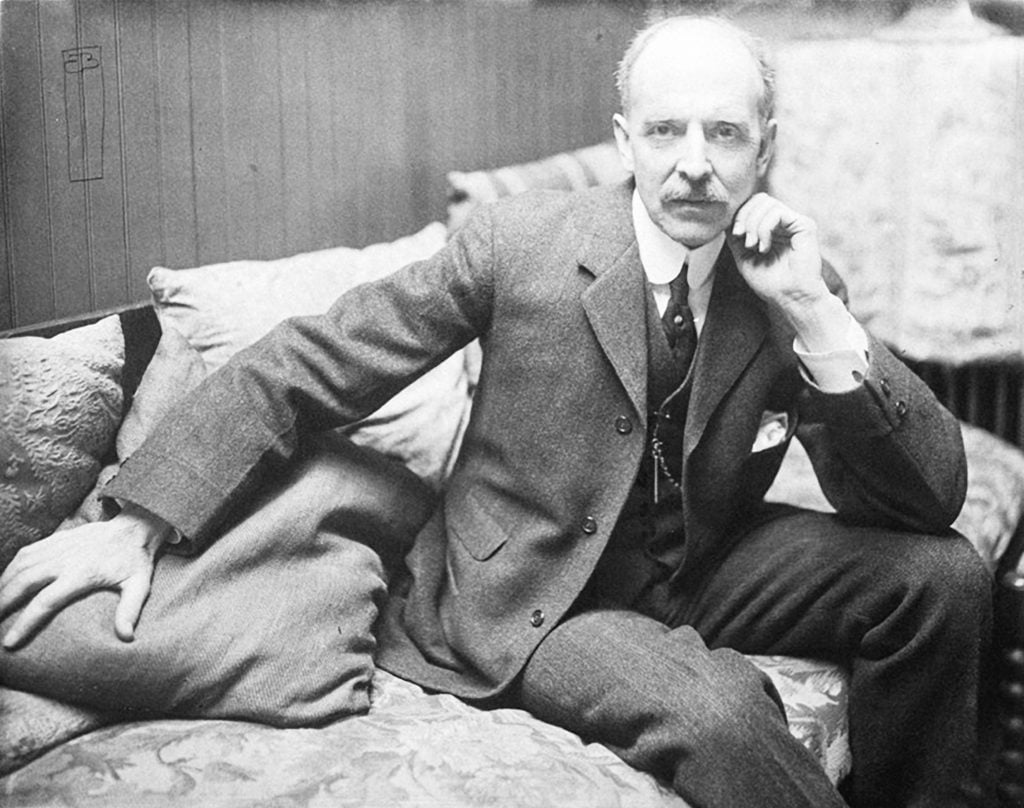

French was one of the leading lights of the American Renaissance (1876 to 1917), which his career neatly bookends. His first mature commission, the Minute Man memorial in Concord, Massachusetts, came in 1875; Abraham Lincoln, perhaps his last major work, in 1920.

In his day, French was championed by the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson and studied in Florence on his way to nationwide fame, collaborating on numerous occasions with Henry Bacon, the Lincoln Memorial’s architect. Now, French’s forgotten legacy has been unearthed in a new documentary by filmmaker Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

But Daniel Chester French: American Sculptor also highlights other figures whose contributions to the nation’s monuments were never properly recognized—the Italian artisans who brought artists’ designs to life in marble, and the models who posed for the sculptures, such Hettie Anderson, an African American woman whose face is immortalized in major civic works by French and many of his contemporaries.

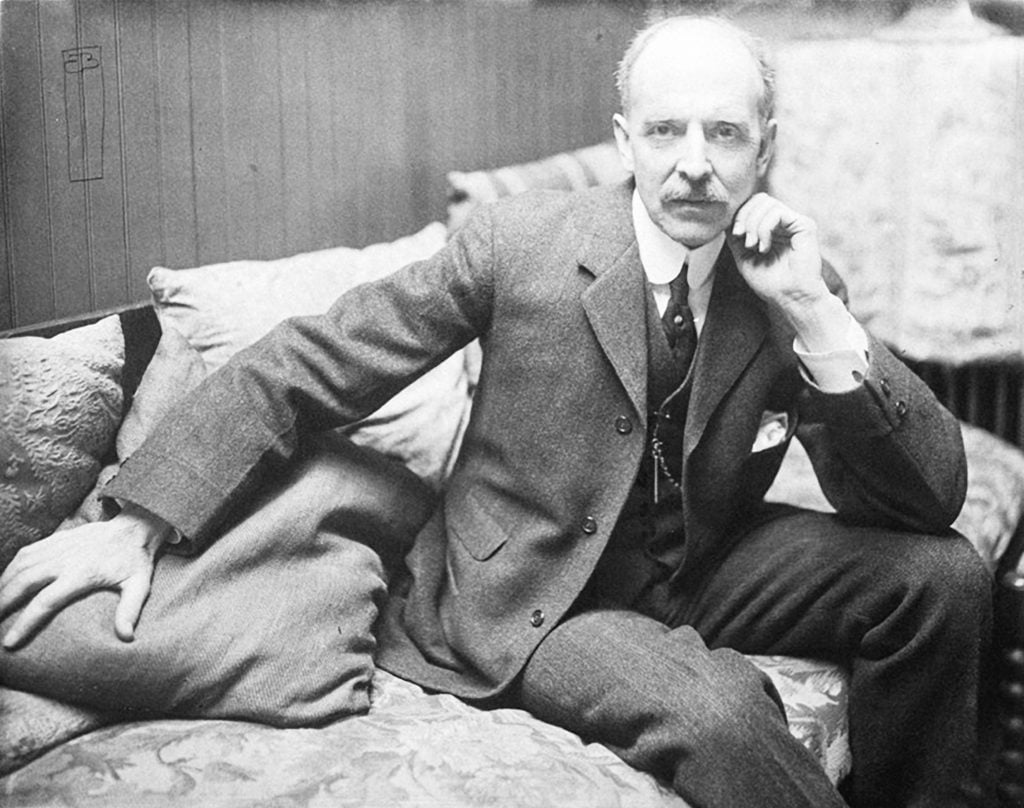

A historic photograph of Daniel Chester French. Photo courtesy of Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

The film premiered in May—timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the unveiling of the Lincoln Memorial—at the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. That’s just down the road from Chesterwood, French’s summer home, studio, and garden in Stockbridge. Montes-Bradley plans to take it on the festival circuit in the fall.

Ahead of the Fourth of July holiday, we interviewed the director about the project and why he was compelled to share the artist’s story.

What did you know Daniel Chester French before you began working on this film?

A few years ago, I did film called Monroe Hill, about the life of James Monroe during the French Revolution. The curator of the Monroe papers at the time, Daniel Preston, asked if I had heard of Daniel Chester French. I said I had not. It turned out Preston was also the curator of the Daniel Chester French papers. And he told me French did the Lincoln Memorial.

That sparked something. Growing up, the Lincoln Memorial was very important to me. It is the first thing that people think about when they think about the United States. When they think about New York, they think about the Statue of Liberty, but when they think about the country, it’s the Lincoln Memorial.

So I went to Washington, D.C., and I went to the Lincoln Memorial, and I asked every tourist for about four hours if they knew the artist. And they all said, “No.” I thought, “This needs to be remedied.”

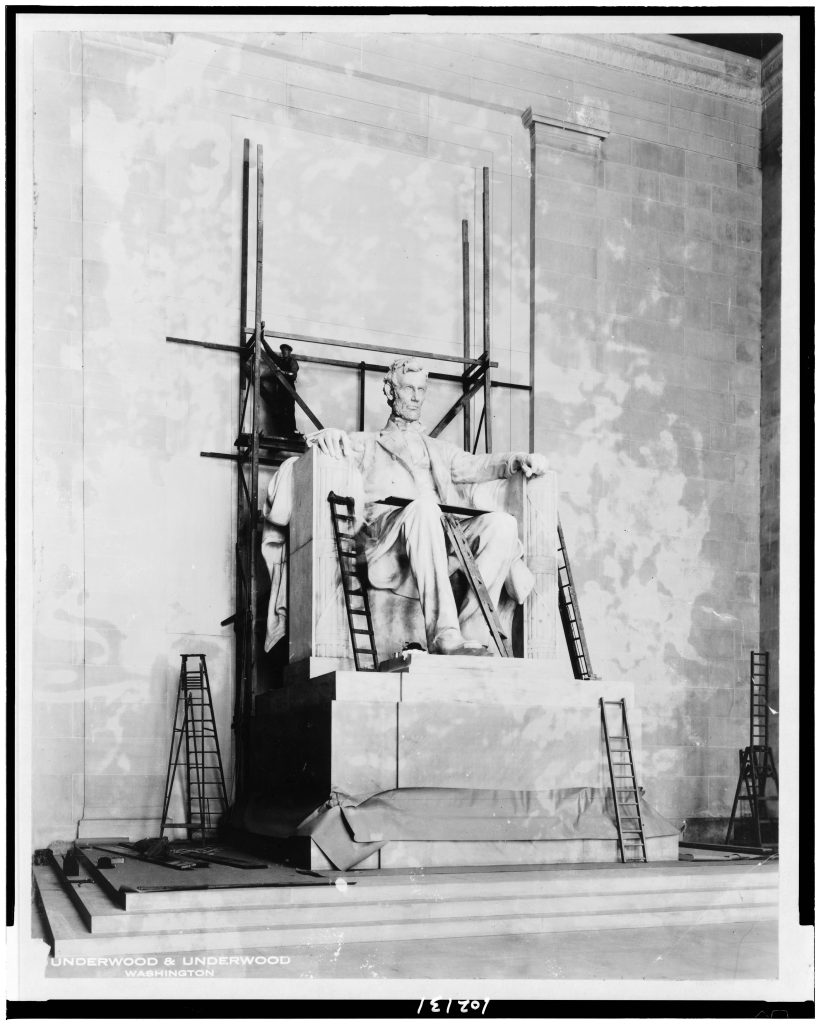

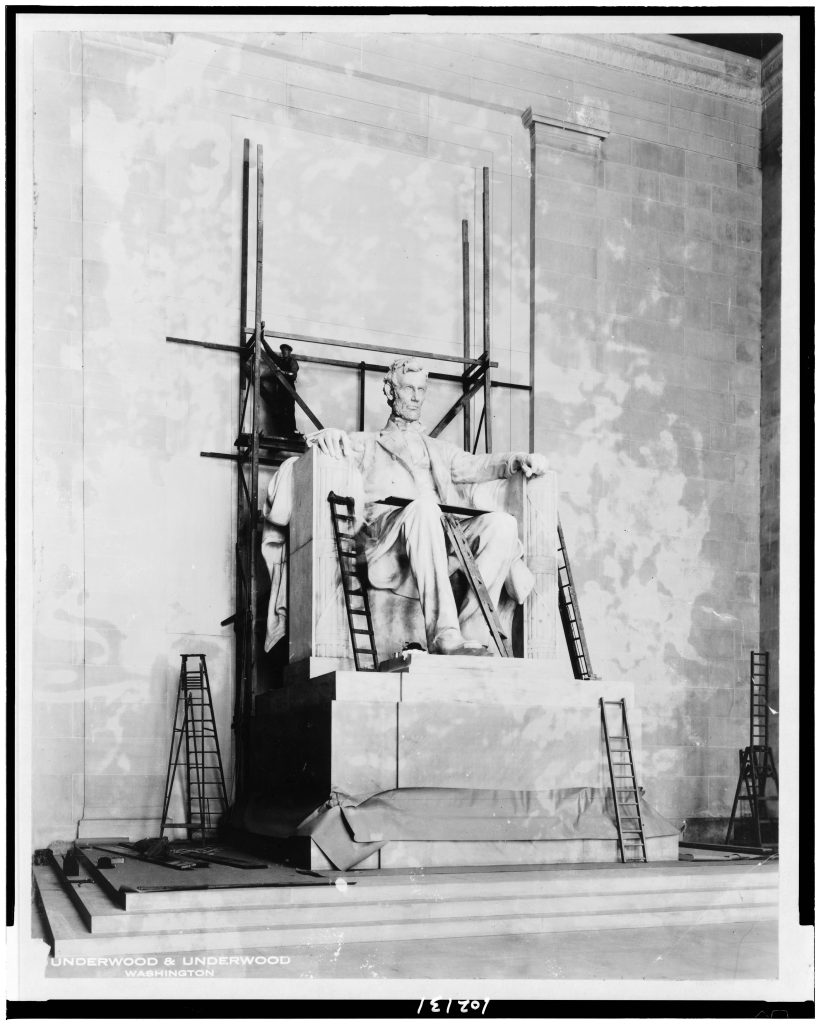

Daniel Chester French, Abraham Lincoln under construction in a historical photograph taken at the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

I did not know the name Daniel Chester French, but funnily enough, right before I put on your movie, I was watching an episode of Impractical Jokers where one of the cast got in trouble for climbing on a statue at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York. As I watched the film, I realized it was one of the Four Continents by French!

I actually originally included that in my movie, but then I took it out because I didn’t want to encourage people to touch the statues—which they shouldn’t, because it’s a federal crime.

Eduardo Montes-Bradley at sculptor Daniel Chester French’s main studio at Chesterwood. Photo by Lisa Vollmer.

As the Impractical Jokers learned the hard way! Watching the film, I noticed that you did not include much information on French’s personal life, instead focusing on his work. Was it difficult to find those details, or was that an artistic choice?

Daniel Chester French’s wife and his daughter both wrote biographies which have a lot of personal details. And the historian Harold Holzer did another biography [Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French]. These three works aim at the personal experience.

But I don’t necessarily think that the personal life of Daniel Chester French would explain the importance of the Lincoln Memorial, which has to do with a very particular time in the life of America. For me, the protagonist of the film is the nation and the creative process.

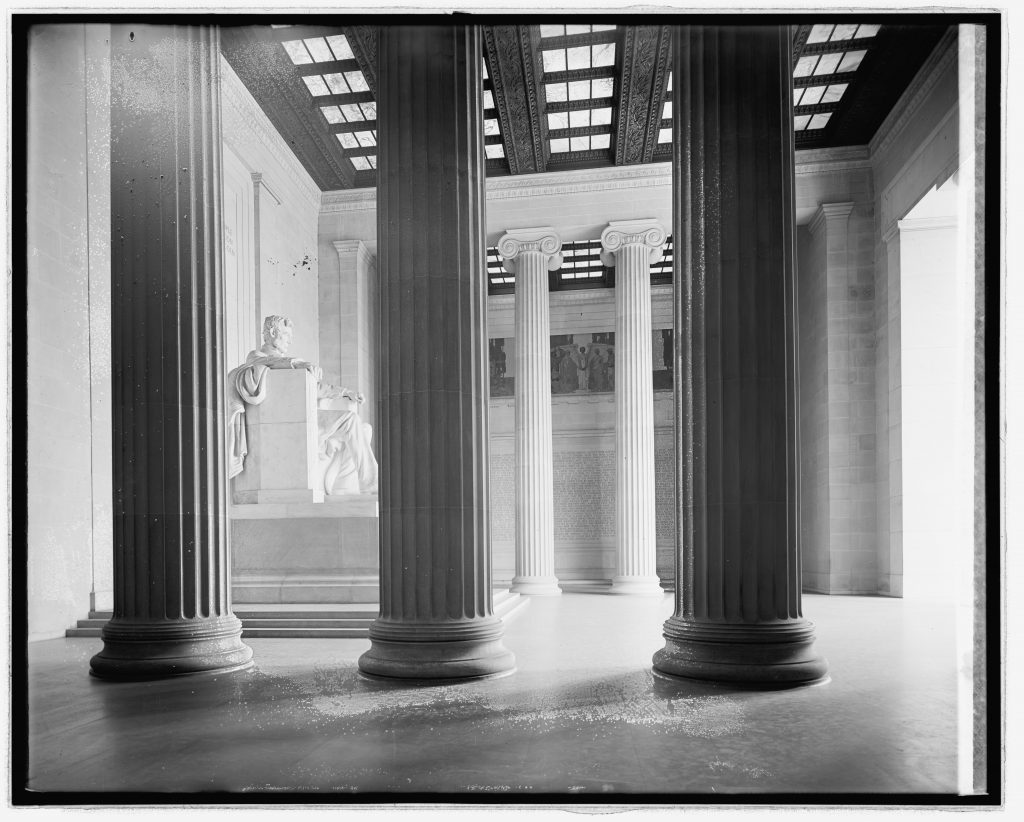

Daniel Chester French, Abraham Lincoln in a historical photograph taken at the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

Obviously, the film really illustrates the extent to which French helped shape the civic landscape of our country. For you, what was the most surprising thing you learned while making the film?

I think that the greatest revelation to me was that the canon teaches us that it was middle aged, white, Anglo Saxon men working to create that landscape, men like Daniel Chester French and Augustus Saint Gaudens.

But those men were not alone. Their works were carved by Italian immigrants. The models were of all extractions, including African Americans like Hettie Anderson. What surprised me the most was to see how diverse the art and craft of monument-making was at the time.

Today, we are trying to put an emphasis on the importance of diversity. We should also revisit the 19th century to give proper credit and to understand that it was diverse. We just couldn’t talk about it, and we failed to document it.

Daniel Chester French, Richard Morris Hunt Memorial, on the perimeter wall of Central Park, at Fifth Avenue at 70th Street, in a historical photograph. Photo courtesy of Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

For people in New York, where would be they surprised to see French’s work right in front of their noses, perhaps?

If you visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art and go for a walk afterward heading south on Fifth Avenue, the first monument you’re going to find on the right is Daniel Chester French’s Richard Morris Hunt Memorial. Hunt was the architect for the Met and the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

New Yorkers are surrounded by art that is constantly speaking to them. It’s up to us to listen, but the stories are there. All you have to do is look into the eyes of these brass and bronze and marble and stone and granite figures and ask, “Who are you? Why are you looking at me?” And you’ll be fascinated by the answers.

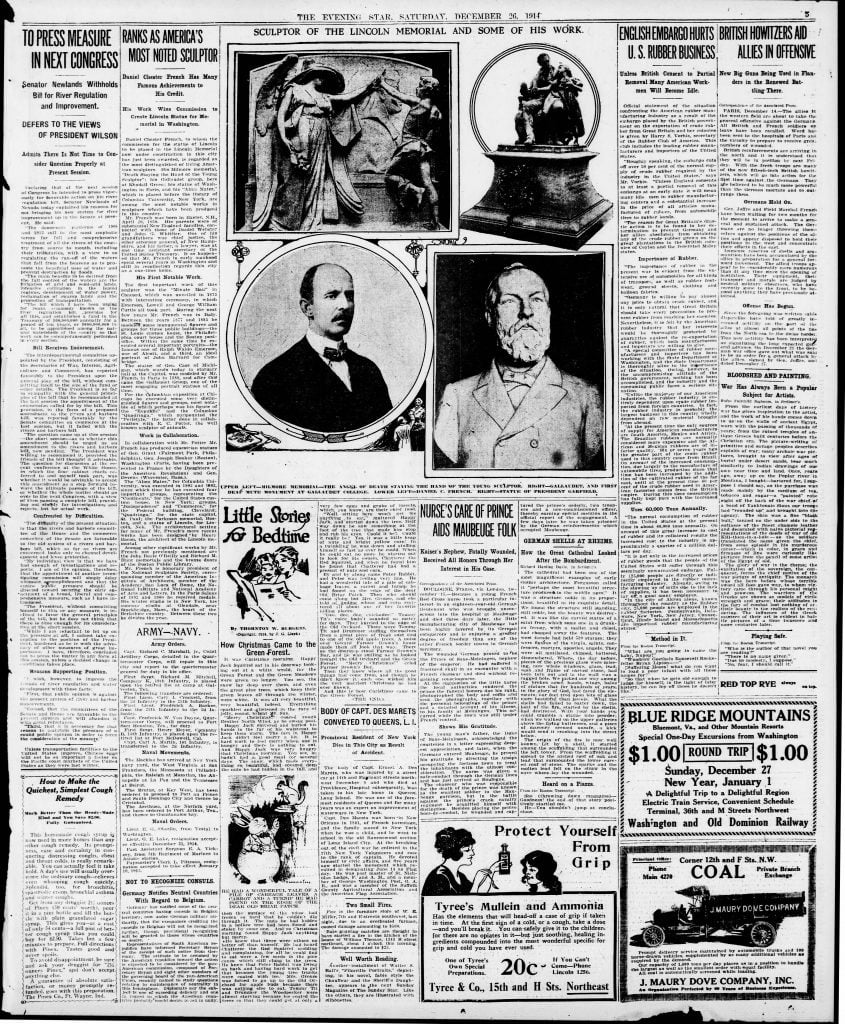

A historic newspaper article claiming Daniel Chester French “ranks as America’s most noted sculptor.” Photo courtesy of Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

Why do you think French’s name is not better known today, despite the lasting fame of his Abraham Lincoln?

The Lincoln Memorial is a temple of democracy. From the beginning, that monument and that statue inside became a place of worship.

And it’s very difficult to come out of the shadows of Abraham Lincoln. The figure is so imposing and so powerful—and it was meant to be that way. When you get to the monument, you feel like an ant, you feel like nothing, you feel insignificant. His presence is that of a titan. It’s very Michelangelo-like. It’s our David.

But Modernism happened and representational sculpture became passé. Also it required a lot of money and support to create these huge sculptures. And only seven years after the inauguration of the Lincoln Memorial, the stock market crashed and there wasn’t money for these kinds of projects.

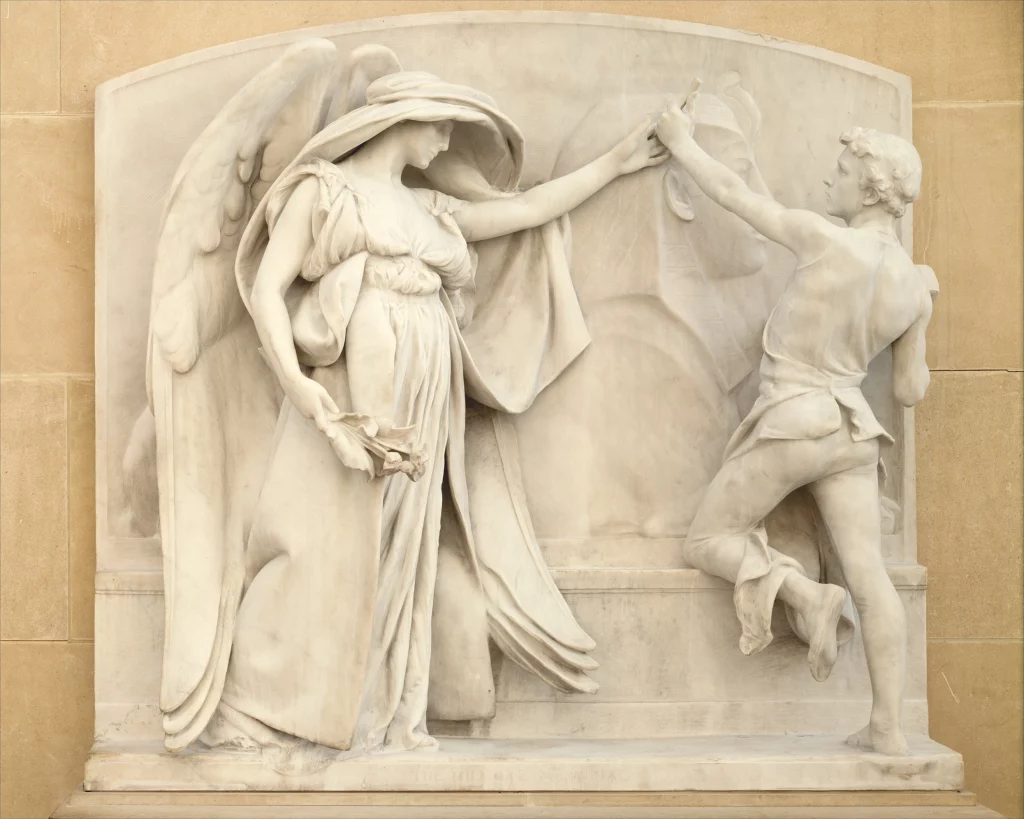

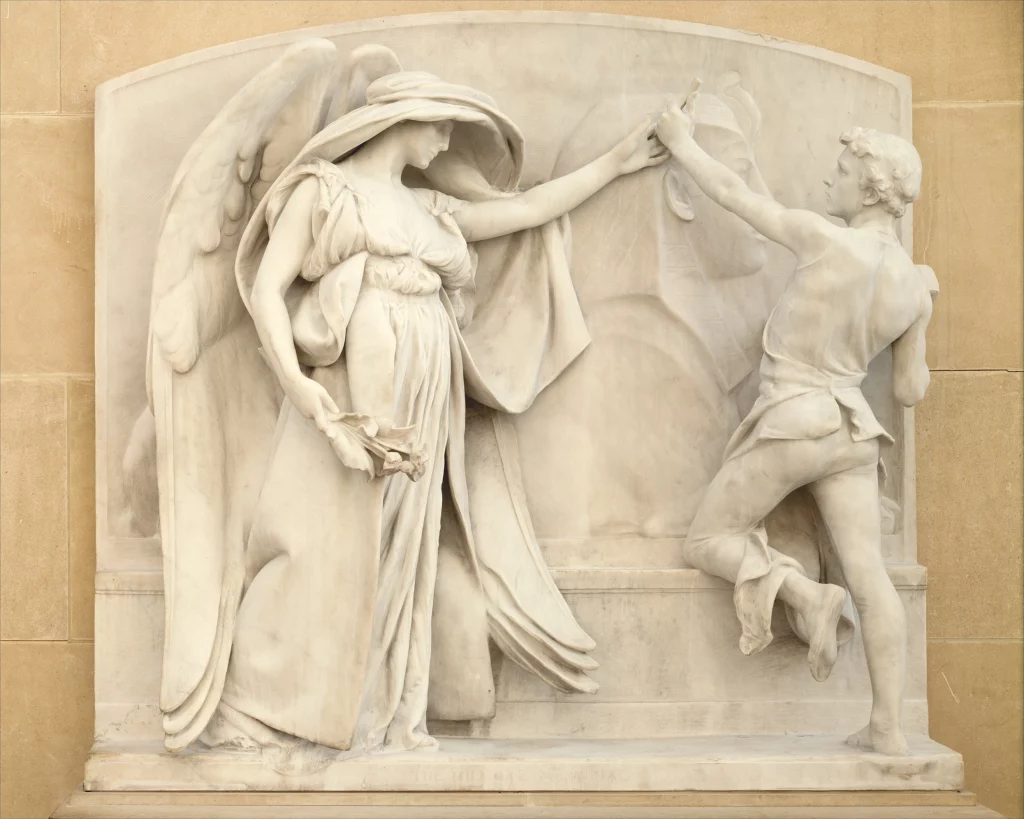

Daniel Chester French, Death and the Sculptor from the Milmore Memorial (1889–93, carved 1921–26). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Do you have a favorite work by French and why?

Probably the Milmore Memorial in Boston, also known as Death and the Sculptor. There is a marble replica in the Met in the American Wing.

The fear of every artist is not to complete their journey. In that monument, you see the hand of death approaching in a gentle manner and taking the hand of the sculptor and saying “no more—that’s as far as you’ve gone. You have to leave your work unfinished.”

That’s one of my greatest fears. I don’t know which will be the film I will not be able to complete because death will come and stop my hand. And that’s why I’m rushing into my next project!

And what is that?

It’s called An Italian Factor and it’s a film about Italian sculptors in America.