In the art world, you don’t often hear the name Darlene Lutz. She doesn’t own a gallery. She’s not an auctioneer. She isn’t intimately tied to any big-time, blue-chip artists, or even any rising stars. Her claim to fame actually doesn’t come from the art world, strictly speaking. Instead, it stems from an acrimonious lawsuit against her onetime friend Madonna.

It was a case made in tabloid heaven. In early 2017, Lutz, who makes her money as an art advisor, attempted to sell off a cache of personal effects that once belonged to the singer through the New York-based auction house Gotta Have Rock and Roll. Among the items were costume lingerie worn by Madonna during performances, a brush full of hair, and—most famously—a letter sent to Madonna by Tupac Shakur while he was in prison in which he ended their romantic affair.

Madonna sued, contending that she had been unaware that she no longer owned the objects that Lutz was selling. The singer wrote in her complaint that Lutz had “betrayed my trust in an outrageous effort to obtain my possessions without my knowledge or consent.” In July that year, a judge passed a temporary motion halting the sale of 24 of the lots.

But the victory was short-lived. This June, Madonna finally lost her suit, in part because it fell outside of a three-year statute of limitations, but also because a separate 2004 lawsuit against Lutz (more on that later) ended with an agreement that Madonna would not pursue any legal claims against her former art advisor.

“The court came to the absolute right decision,” Gotta Have Rock and Roll’s lawyer, Hartley Bernstein, told Reuters. “The property is Ms. Lutz’s to do with as she wishes.”

In a meeting with artnet News late last month, Lutz framed it a little differently. “Why shouldn’t I be able to make money off this?” she asked. “When did it become a sin to make money?”

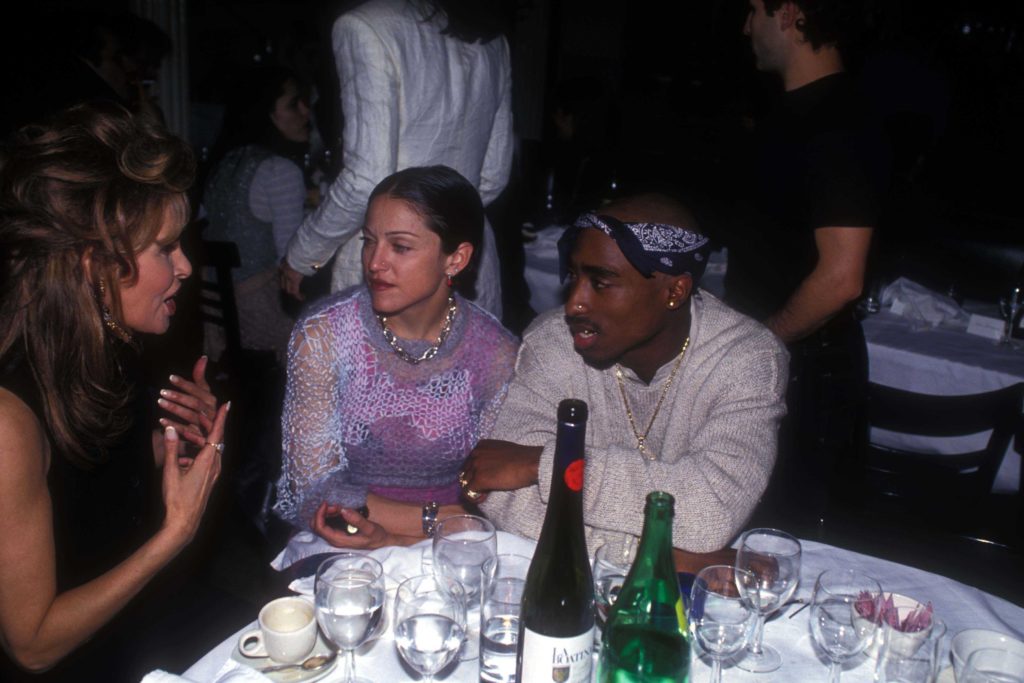

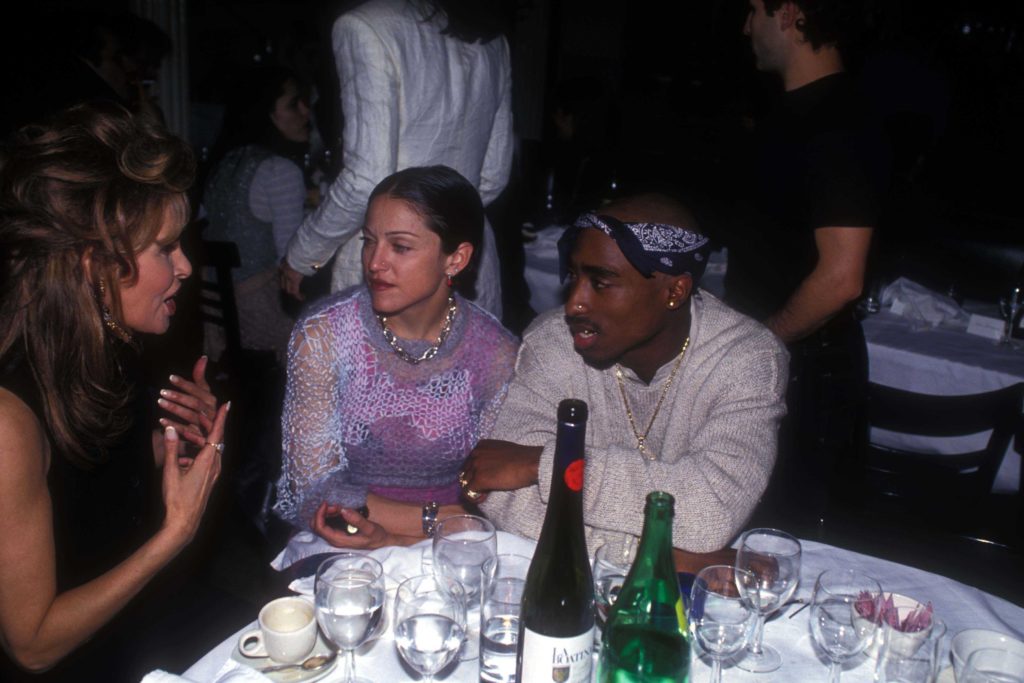

Raquel Welch, Madonna, and Tupac Shakur at the Interview Magazine party in March 1, 1994 in New York City. Photo by Patrick McMullan/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

The Good Ol’ Days

Before we get to how exactly these personal effects ended up in Lutz’s hands, it’s useful to have some sense of her background and how she and Madonna became close.

A native of Wisconsin, Lutz studied art history at the University of Wisconsin before moving to New York, where she helped an art dealer who specialized in Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Pre-Raphaelite, and Symbolist paintings open a gallery. Later, she took up further studies at New York University and began writing for a French art magazine.

She met Madonna in 1981 through the late art-world man-about-town Glenn O’Brien, who at the time was dating Lutz’s housekeeper. “Madonna and I came up together in the early days in New York,” she says. “It was a pretty small world downtown.”

According to Lutz, they soon embarked on a long, fruitful business relationship of more than two decades, from 1983 to 2004—but not only that. Lutz also says she was deeply involved in helping the singer craft her image as a pop icon.

“Madonna shifted culture, but she didn’t do it all by herself,” the art advisor says. (Representatives for Madonna did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.)

The 1993 Girlie Show World Tour, for example, was named for Edward Hopper’s 1941 painting Girlie Show, which Lutz says she arranged to have installed in Madonna’s living room.

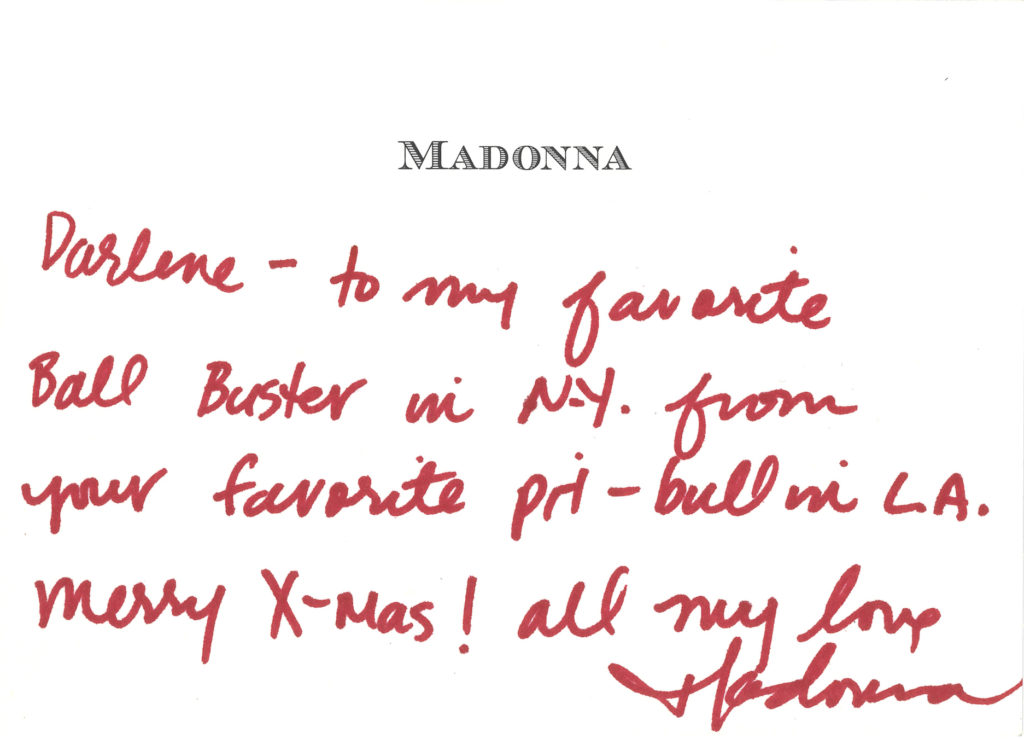

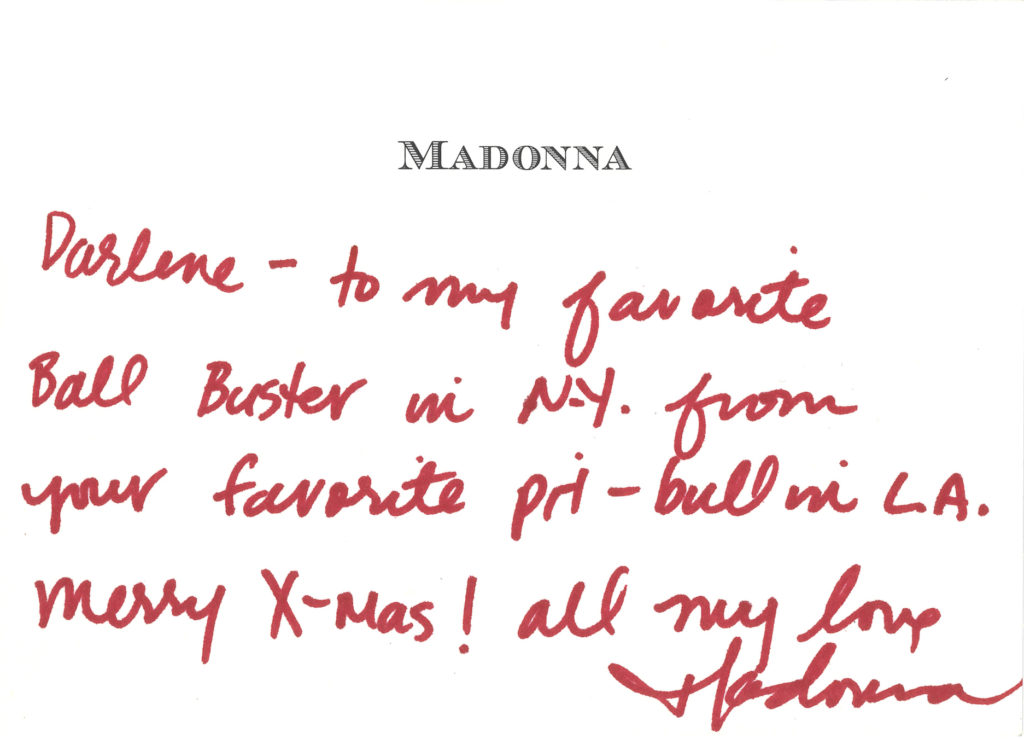

Madonna wrote this note to Darlene Lutz. Courtesy of Darlene Lutz.

Lutz also helped shape Madonna’s art collection by casting a wide net, purchasing everything from works by Old Masters (including a painting by the Master of 1310) to Modernist treasures by artists such as Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder, and Francis Bacon, as well as lesser-known figures such as Polish artist Tamara de Lempicka. And though Madonna wasn’t big on contemporary art, Lutz says she convinced her to add works by artists such as Lisa Yuskavage and Marilyn Minter, whose work explores sexuality and the female body, to her collection.

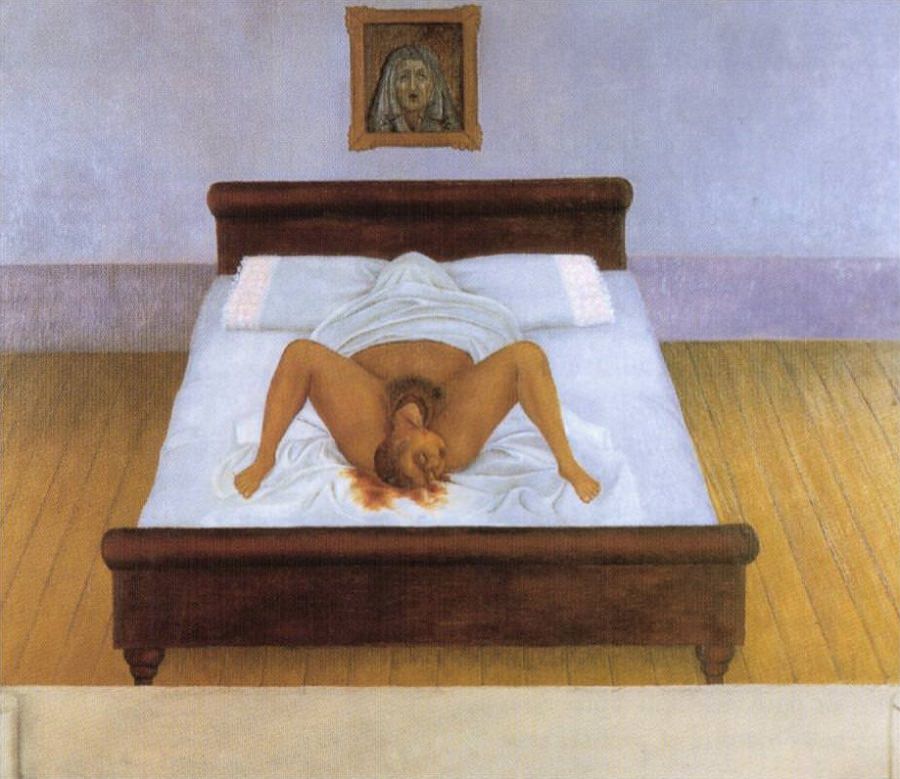

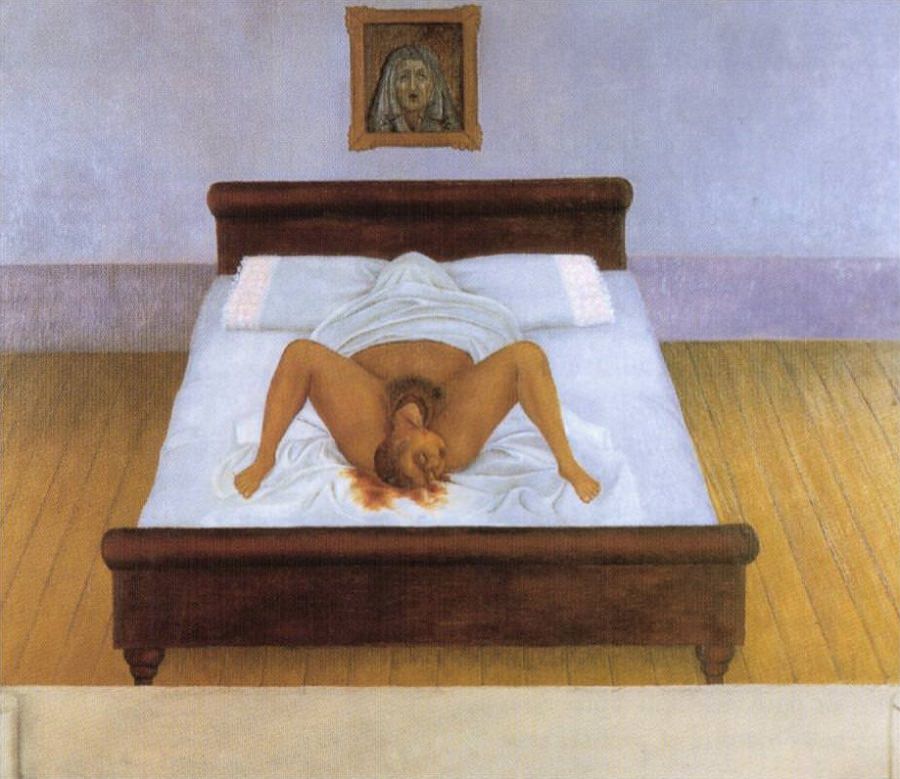

Lutz estimates that she acquired millions of dollars worth of art for Madonna, and that she added around 230 works to the singer’s collection. Among her major successes were the acquisitions of two paintings by Frida Kahlo, My Birth and Self Portrait With Monkey.

“I introduced Madonna to Frida Kahlo,” she says, noting that the singer absorbed Kahlo’s influence and her performative approach to style. “Ten years before Selma Hayek [played Kahlo in Frida] Madonna and I took a trip to Mexico. She wanted to do a Frida Kahlo movie,” she adds. “Now I think, oh my God, if she tried to play a Latina!”

Signs of Trouble

In the early 2000s, their relationship began to sour. According to Lutz, the dispute stemmed from a quartet of 19th-century paintings, collectively valued at around $500,000, that she was asked to sell on Madonna’s behalf. But after the pictures were already delivered to the buyer, the singer changed her mind, Lutz claims.

“She wanted the paintings back, and I said ‘no,'” Lutz says. “The deal had already been done.” Madonna filed a lawsuit that was settled in 2004, with the agreement that Lutz pay Madonna a fixed sum. The terms also dictated that Madonna would release Lutz from any further claims.

“I have an iron-clad settlement,” Lutz insists.

According to Lutz, the agreement also gave her sole ownership of a cache of items that belonged to Madonna that had since come into Lutz’s possession—which is where the Tupac letter and the other items in the Gotta Have Rock and Roll sale come in.

Darlene Lutz consigned Madonna’s hairbrush to auction. Photo courtesy of Gotta Have Rock and Roll.

About that Hairbrush…

Over the decades, Lutz came to possess these and other items through all sorts of curious means. Some of them came to her after Madonna used Lutz’s loft as storage, and then forgot about what she left behind. Other items, such as a cache of cassette tapes, were left behind by Madonna’s brother, Christopher Ciccone, who Lutz says later told her she could do whatever she wanted with them. (Madonna argued in a deposition that the tapes weren’t Ciccone’s property.)

“A lot of the things I purchased and she wore [during performances] because she didn’t have any money,” Lutz says. The adviser is quick to point out that she was auctioning off a lingerie stage costume originally purchased at Macy’s, not Madonna’s personal undergarments, as was misreported by the press. (A pair of underwear consigned by a man who once dated Madonna was among the lots from the planned auction hit with the temporary restraining order back in 2017.) “Those panties will be in my obituary,” Lutz laments.

Underwear aside, how does Lutz justify keeping all the other strange ephemera? What could she have wanted with Madonna’s personal hairbrush?

Frida Kahlo, My Birth (1932).

“My interest has always been in artists, and Madonna is clearly an artist,” Lutz says. (She also points out that there is a long history of saving hair as a keepsake or collectible.) “There was no question Madonna was on a trajectory to fame and celebrity. And with artists, you don’t always know how their history will be written. Ephemera can be markers of that. I ended up with a lot of stuff, particularly fan mail and fan art, because it was going to be thrown out.”

“Look at other artists. Prince didn’t get it together. Michael Jackson didn’t get it get it together. Neither of them expected to be exiting before they created their own legacy. I was trying to get Madonna to do that. But when you look at your legacy you’re looking at your own mortality and that’s something that most people don’t want to do.”

Recently, Lutz was considering donating some of these items to a museum. But with Madonna back in the news thanks to the release of her new album, Madame X, now seems like a good time to sell. Next week, the Tupac letter will be made available for sale through Gotta Have Rock and Roll and could fetch an estimated $300,000.

“As much as I’d like to be philanthropic,” Lutz says, “someone needs to buy it and give it to a museum because I have lawyers to pay.” (A survivor of breast cancer, she is also planning to donate a portion of the proceeds to breastcancer.org.)

“I can’t tell you the the physical toll, the emotional toll, and the financial toll this is taken,” she says, calling the past two years “a living hell.” Madonna’s lawyers, she adds, want to “litigate me either into bankruptcy or the grave, whichever comes first.” If there’s a further appeal, Lutz says she may have to resort to crowdfunding to pay for her defense, but she remains confident that she’ll prevail.

But looking back, Lutz suggests that she should perhaps never have been surprised. “Madonna is who she is she always has been,” she says. “She’s never changed.”