Art & Exhibitions

The Brant Foundation’s Dash Snow Exhibition Revisits the Art and Life of a Downtown Icon

The show will include over 100 never-before-seen Polaroids.

The show will include over 100 never-before-seen Polaroids.

Cait Munro

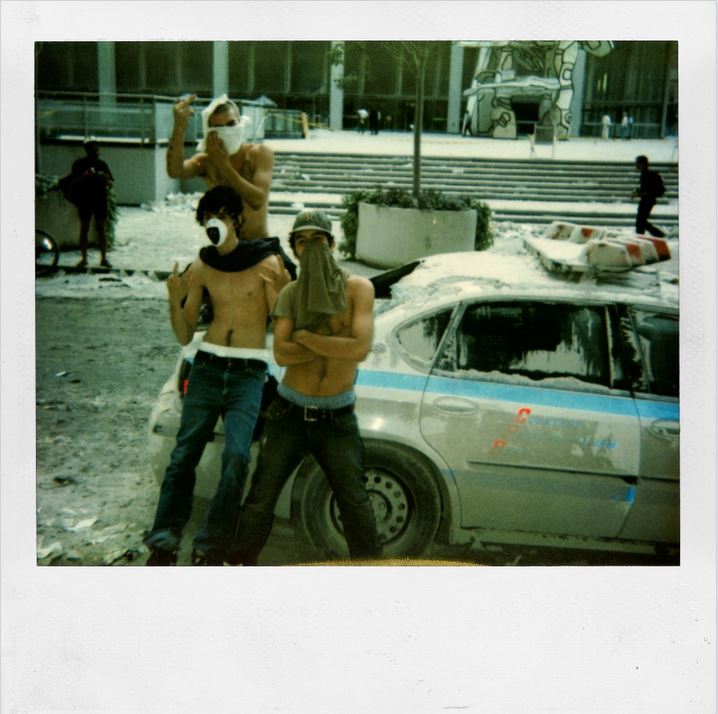

Untitled (Polaroid #17), 2005. C-Print, 20×20 inches. Courtesy of the Dash Snow Archive, New York City.

In 2007, Dash Snow and Dan Colen, two esteemed art world “bad boys” took over Jeffrey Deitch’s Grand Street gallery space, transforming it into a so-called “hamster’s nest” filled with 2,000 phone books that it took 30 volunteers three days to shred. In the transformed space, the artists held four all-night, no-holds-barred extravaganzas in which they invited their friends to occupy (and basically destroy) their surroundings from midnight until 8 a.m. After the partying was over, guests were invited to view the detritus of their bacchanalia as an art installation and thereby get a view onto the wild world of Snow and his cohort that, up until then, was only accessible through the Polaroids Snow famously took during similar nights of revelry in an attempt to reclaim what he couldn’t otherwise remember.

It was this conflation of his life and art that made his work so appealing. Just six years after Snow’s harrowing and untimely death in 2009, the exploits of the artist and his friends are the stuff of urban legend. He is remembered as much for who he was as he is for what he made.

On November 8, the Brant Foundation will offer a look into Snow’s life and work with “Freeze Means Run,” his first solo museum show in the US, and an exhibition that will span a variety of media including collage, large-scale sculpture, video, and photography. While it will not give viewers a recreation of the Hamster’s Nest, it will present over 100 of Snow’s previously unexhibited Polaroids. Conceptualized by the Dash Snow Archive with the aid of friends and fellow artists Colen, Nate Lowman, Hanna Liden, and Snow’s last partner Jade Berreau, the show will offer a display that is as close as possible to something Snow himself might have assembled.

Sisyphus, Sissy Fuss, Silly Puss, 2009, HD video projection from Super8 film original

Courtesy of the Dash Snow Archive, New York City.

“With Dash, I’ve learned, there’s always this interest in him as a person,” Dash Snow Archive director Blair Hansen said during a phone interview. “He helped to form that desire in people because his work is so immediate and you really feel like you’re seeing him in the work. But it’s also a little bit of a mirage, and I think the work says something more—or at least way different—than anything we could ever know about his biography.”

Unfortunately this personal connection audiences feel becomes skewed, manifesting as a shallow obsession with the lurid minutia of Snow’s biography that shifts the focus from his work to his folkloric image. “Biography,” Hansen notes, “is a slippery slope,” and viewing Snow’s work through this lens often reduces the impact of the key social and political messages that the work also contains.

With the peerless perspective provided by a few years time, “Freeze Means Run” hopes to reignite and refocus the conversation around Snow’s work, emphasizing its complexity, its enduring nature, and its often extraordinary prescience.

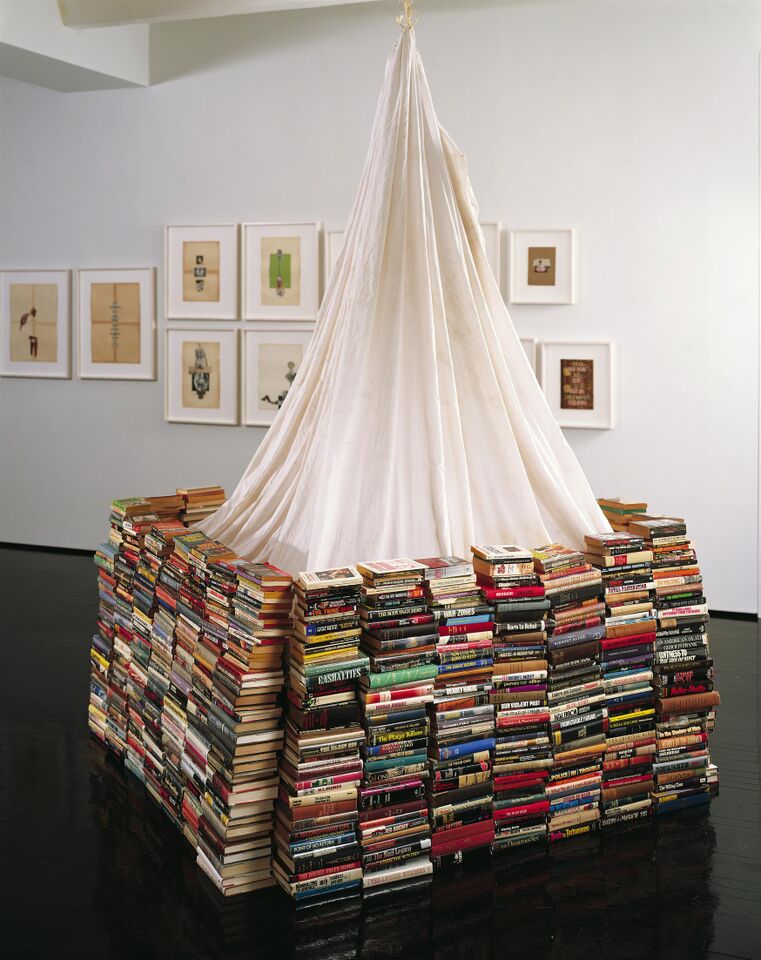

The centerpiece of the exhibition, according to Hansen, is Untitled (Book Fort), a 2006 sculpture created from hundreds of books—mostly tomes written by fringe philosophers, many centered on anarchic themes—stacked to make a kind of tent-like structure.

“I think it’s probably the most important sculpture that he made,” Hansen said. “It’s like a hideout. You imagine Dash inside of it. He was a really avid collector, he liked radical philosophy, and so it’s nice to set the stage with that piece.”

Book Fort, 2006-07, Mixed Media, 141.7 x 74.8 inches (format variable) Courtesy of The Dash Snow Archive, New York City, and Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin / Photo: Jochen Littkemann.

Also of note is Fuck the Police, the iconic, 45-piece collection of newspapers emblazoned with headlines recounting instances of police violence and splattered with semen in a brazen, valiant statement that feels no less politically relevant or necessary ten years after its creation.

Along with the Polaroids and the aforementioned Dionysian performance, these begrimed newspapers are the works he’s most widely known for. And while the most talked-about aspect has (for obvious reasons) typically been the use of his own semen, looking at the work today, the more remarkable matter is how easily it could have been created just this year.

While Fuck the Police reveals how perilously little has changed socially in the United States in ten years, Snow’s video and Polaroid works make the opposite statement with regard to technology. One of the last truly analog artists, Snow was known for refusing to have a telephone or a computer. He also neither uses the Internet, nor took digital photographs. As a 2007 New York magazine profile noted, the only way to contact Snow was to “go by his apartment on Bowery and yell up.” It’s another prime example of Snow living his art, but it is also a practice that would be extremely difficult to maintain in today’s self promotion-obsessed e-culture.

“He really didn’t like those technological developments. He was distrustful of them in almost the same way that he was distrustful of the government or the police. He really didn’t like the hegemony of all of that, and he really resisted it wholeheartedly,” Hansen recalls.

In addition to the rare Polaroids, all of which were shot between 2000 and 2009, the films Familiae Erase (2008), Sisyphus, Sissy Fuss, Silly Puss (2009), and Untitled (Penis Envy) (2007), will be shown. Both Sisyphus and Familae Erase were shot on Super8 film and edited “in-camera,” without any post-production revision—a testament, Hansen notes, to Snow’s ability to be simultaneously deliberate and spontaneous, gently nudging his art just enough without allowing it to lose its rawness.

Dash Snow, Fuck the Police (2005).

Photo: Saatchi Gallery.

Hansen is careful to clarify that the exhibition isn’t a retrospective, but rather a carefully considered look at the various works of an extremely enigmatic artist across a variety of disparate media. There will be no “hamster’s nest” here. The gang has grown up, and while its truly anybody’s guess what Snow would have done given free reign of the sprawling, sun-soaked Brant compound, or what his artistic response would be to countless cultural and political events that have occurred in his absence, the takeaway is that Snow’s legacy is still very much alive in ways that have yet to be fully examined.

His daughter Secret, now eight, will attend one of her father’s exhibitions for the first time, despite the fact that, as Hansen notes “there’s really no way to make a Dash Snow show appropriate for children.”

It feels fitting that this major artistic achievement should be staged at the Brant Foundation—publishing magnate and mega-collector Peter Brant has been a longtime collector and champion of Snow’s work as well as that of his contemporaries. Dan Colen’s 2013 exhibition at the compound was also famously done as a tribute to Snow.

“It made sense to show this work, I think, for everybody,” director Allison Brant said in a phone interview. “We have a relationship with the artists that we show and we are able to give them the freedom that other spaces often can’t provide. It’s something that I think is at the heart of the Brant Foundation…. Everyone really had the desire to be authentic in the way that this work is shown, and to do what [we think] Dash probably would have done.”