Art & Exhibitions

David Ebony’s Top 10 New York Gallery Shows for September

Nick Cave, Morris Louis, Prune Nourry, and others, reviewed.

Photo courtesy of Dominique Levy

Nick Cave, Morris Louis, Prune Nourry, and others, reviewed.

David Ebony

1. Roman Opalka at Dominique Lévy, through October 18

“Roman Opalka: Painting ∞” is a rare US tribute to the work of the late French-born Polish artist whose obsessive, lifelong endeavor is unique in contemporary art. The infinity sign in the show’s title is key because at the core of the artist’s project, as he affirms in a statement in the exhibition’s excellent catalogue, is an “attempt at visualizing time.” In 1965 he embarked on a series of large paintings of uniform size (77 3/16 by 53 1/8 inches) filled with tiny rows of neatly inscribed white numbers on nearly monochrome gray backgrounds. A dozen riveting examples are included in the show. In the series, “1965 / 1- ∞,” Opalka started with the numeral 1 and sought to reach infinity. He devoted the rest of his life to that goal, but his own mortality abruptly intervened. At the time of his death in 2011, at age 79, he had painted over five million numerals on 233 canvases. Each canvas bears 20,000 to 30,000 consecutive numbers.

Chronicling his physical existence as well as his life in art, he took a single black-and-white headshot photograph of himself standing before each completed canvas, and also regularly recorded himself reciting the numbers as he painted them. Seven self-portrait photos spanning his adult life are also included in the exhibition. Another highlight of the show is a group of early works making their US debut. Mostly ink-on-paper pieces, some double-sided, these abstract gestural compositions from the late 1950s and early ’60s, correspond to European tachisme or art informel. The feverish, overwrought lines crowding these densely packed compositions bear the obsessive quality of his later endeavor.

Paul Graham installation view

Photo: Courtesy Pace Gallery

2. Paul Graham at Pace, through October 4

The British-born New York photographer Paul Graham beckons viewers into a dream state of his own devising in “Does Yellow Run Forever?,” a stunning exhibition of recent, mostly large-scale works. As in a number of Graham’s previous exhibitions, the works are hung unconventionally, many reaching toward the floor or ceiling rather than eye-level. The installation thus engages the viewer in a kind of visual workout immediately upon entering the gallery space.

There are three recurring themes or images throughout the 30 pieces in the exhibition. One series shows rainbows rising above verdant, bucolic landscapes in Ireland. The second features a sleeping woman in bed—the model is the artist’s partner asleep in different bedrooms, taken at various locales during the artist’s recent world travels. The third group consists of urban street scenes in Harlem or the Bronx, with tawdry-looking gold and jewelry exchange depots and pawn shops central to the picture. Is the woman dreaming of the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow? Will the venders in these abject pawn shops exchange the gold for cash? In the end, these haunting images seem to explore the endless cycle of aspiration and desire.

Nick Cave, Rescue (2013)

Photo: Courtesy Jack Shainman

3. Nick Cave at Jack Shainman, through October 11

This two-part show of recent works by Nick Cave, occupying both of the gallery’s Chelsea spaces, has two distinct themes. “Rescue,” installed at 24th Street, contains a series of works featuring found ceramic dogs, each ensconced in elaborate settings, surrounded by artificial flowers and plants, glittering toys, and other found objects. In each of these pieces, Cave idealizes images of happy pups that have been saved from destruction and now reside in canine heaven. Rather than campy sentimentality, which the works’ components might suggest, these sculptures effectively convey the honorable attributes of loyalty, devoted companionship, and courage, characteristic of all cherished pets, but mere aspirations for most human beings.

The Missouri-born, Chicago-based artist is in a far more provocative mode in “Made for Whites by Whites” the second part of the exhibition, on 20th Street. Here, Cave explores the remnants of deep-seated racism that still exist in American culture, via old artifacts the artist acquired in flea markets and yard sales. Caricatures of black men in figurines and other found objects are embedded within elaborate installations that tend to neutralize the meaning of the objects by physically removing them from their original context. Nevertheless, by isolating these antique artifacts, Cave manages to underscore their vitriolic intent.

Roxy Paine, Checkpoint (2014)

Photo: Courtesy Marianne Boesky

4. Roxy Paine at Marianne Boesky, through October 18

For some years, the New York artist Roxy Paine has incorporated computerized machines in his work to create drawings, paintings and even to mimic the effects of erosion on sandstone, forming a miniature Grand Canyon. Paine explored natural phenomena in a series of stainless steel “trees” and dioramas filled with artificial plants. “Denuded Lens” is a show of new works that represent something of a departure.

Here, machines used for surveillance, such as cameras, telescopes, and computers are rendered in unpainted or stained maple wood in awe-inspiring, precisionist detail. Photo-realist sculpture is nothing new, especially with the advent of the increasingly sophisticated 3-D imaging programs. The palpable tension in the exhibition, however, stems from the irony of employing a photorealist technique to describe objects used to aid vision and probe images that are usually invisible to the naked eye.

Scrutiny (2014) consists of a tightly arranged grouping of objects—cameras on tripods, a telescope, plus computer monitors and light fixtures aimed toward a small table crowded with other, unrecognizable contraptions. It is an ominous work, foreboding in its detail because the tools of this probing device look frighteningly emphatic although the purpose of the “scrutiny” is unknown, or at least, unspecified to the viewer. The show’s tour-de-force, Checkpoint (2014), a room-size glass-enclosed diorama, recreates in minute detail all the trappings inside an airport security checkpoint—hand-luggage scanning belt, metal detectors, body scanners, etc. It is a place of enforced exchange, obliging one to trade personal privacy for public safety. Devoid of overt human presence, the work nevertheless conjures the palpable sense of public anxiety that these rooms instill for most air travelers today.

Lisa Mackie, Earth/River (2014)

Photo: Courtesy June Kelly

5. Lisa Mackie at June Kelly, through September 30

Detroit-born New York artist Lisa Mackie is basically a storyteller. The simple tales she conjures act as springboards, allowing her imagination to run free in a wide array of abstract and figurative compositions. She employs an impressive range of mediums and materials, from acrylic-on-silk paintings and resin sculptures, to photography and video projections. In one of her earlier exhibitions, the works centered on the story of a woman who falls to earth. “Earth/River,” the current show of recent works, focuses on a personal exploration of nature. Technically complex yet thematically and visually cohesive, the exhibition offers a quietly immersive experience.

Like most stories, “Earth/River” starts with a book. This one, displayed on a long wood table at one end of the gallery, is more like a handheld assemblage, encrusted with 3-D elements and with some pages caked with thick pigment. Cotton gloves are provided for viewers to peruse the precariously constructed tome. Some pages contain photo images of trees and others feature hand-painted calligraphic texts that hint at a diaristic purpose.

The rich textures and images in the book reappear throughout the show, and a similar cacophony of color permeates the space. A group of large, unstretched paintings features abstract passages that suggest landscape by means of brushwork pulsating in nearly psychedelic hues. Sculptures of purple and green glittering boulders placed on the floor are unlike any rocks I have ever seen. Yet, “Earth/River” is a convincing meditation on nature and a well-realized homage to all its crazy beauty.

Monika Sosnowska, Tower (2014)

Photo: Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

6. Monika Sosnowska at Hauser & Wirth, through October 25

The idea of filling this cavernous gallery with a single, monumental sculpture could have backfired as an overblown exercise in excess. Rather than grandiose and austere, however, Monika Sosnowska’s massive, collapsed Tower (2014) is surprisingly lyrical and inviting. The twisted black-painted steel beams of the structure, splayed on its side, reach over 12 feet high and stretch some 110 feet across the room. Despite its outsized dimensions, the work communicates with the space in a rather understated way, as a dark and abject architectonic feature contained within the rarified architectural space of a well-lit, white-walled Chelsea gallery.

Tower at first appears as a work of formalist abstract sculpture, akin to mammoth pieces by artists like Ronald Bladen or Richard Serra. But the Warsaw-based artist has a distinctive conceptual agenda in mind. She explores in her work the socio-political connotations of the International Style in architecture that emerged in the 1920s and ’30s. For a recent series of works, Sosnowska reconstructed the façade of the Bauhaus in Dessau, designed by Walter Gropius in 1924. Tower is based on Mies van der Rohe’s design for the Lake Shore Drive apartments in Chicago, completed in 1951. Regarded as the epitome of luxury living in the 1950s, the Mies apartment building represented the apotheosis of American capitalism and Space Age optimism. Reduced at a 1:1 scale and presented as though the building’s skeletal structure had suffered some traumatic implosion, Tower recalls a detail of ground zero immediately after 9/11. Sosnowska may not have intended such an equation but the implications are there.

Morris Louis “Veils” at Mnuchin, Installation view

Photo: Courtesy Mnuchin

7. Morris Louis at Mnuchin, through October 18

In recent years, Color Field painting has been enjoying a revival. This show, focused exclusively on “The Veils,” a series of large, resplendent canvases Morris Louis painted late in his career, demonstrates why. Unapologetically beautiful and deceptively simple, the nine mural-size compositions here (averaging 8 ½ by 14 feet), painted between 1958 and 1960, immerse the viewer in a luminous, ethereal space like no other. Centralized on unprimed canvases, translucent pools of color overlap to form gentle yet imposing shapes that are usually slightly flared at the top or sides, like billowing curtains. Tet and Tzadik (both 1958) are standouts here. The muted hue of each painting results from the subtle layering of bright colors that Morris leaves exposed along the edges of the predominant forms. The works may seem effortless or facile but they result from a lifelong exploration of the possibilities of color and abstraction.

Based in Washington, DC, Louis (1912-1962) was a pioneer in the use of early forms of acrylic paint, especially Magna, a type of acrylic resin. The new medium offered increased fluidity and a fast drying time, which allowed for greater continuity of color, form, and texture on a vast scale. Morris, along with his contemporary Helen Frankenthaler, was instrumental in providing new directions for abstract painting in the waning years of Abstract Expressionism. (A handsome show of Frankenthaler’s paintings of the early 1960s is concurrently on view at Gagosian, around the corner on Madison Avenue.) Morris and other Color Field painters used the heroic scale associated with AbEx painting, but eschewed the egotistic and self-referential gesturalism that characterized the earlier movement. Visually sumptuous and conceptually rigorous, “The Veils” look as fresh and provocative today as the time they were created.

Derrick Adams, Fun Fabulous Friends (2014)

Photo: Courtesy Tilton Gallery

8. Derrick Adams at Tilton, through October 18

Colorful and playful, but with serious intent, “LIVE and IN COLOR,” a show of recent works by New York artist Derrick Adams, explores in an imaginative way black archetypes in American culture, specifically as they appear on television. The dozen large-scale collages and sculptures on view show distorted figures on stylized TV screens, many of which feature gaudy test-pattern backgrounds. Employing a Cubist technique that often recalls works by Romare Bearden and more recent collages by Mickalene Thomas, Adams renders TV talking heads and actors in crazy-quilt patterns that eventually settle into a consistent iconography.

Stunts and Shows (2014), a large (approximately four-by-six foot) collage depicts a pair of female figures with arms akimbo, apparently in the throes of a domestic argument. I Come in Peace (2014) is a more intricate, rather Pop-art-related composition featuring a wild figure kneeling on all fours, set against a background of fragmented American flags. Perhaps the most engaging—and jarring—pieces here are the sculptures, in which stylized Cubist heads made of facets of colored paper appear inside the TV sets rather than merely on the screen.

Nicholas Krushenick, Sterling Moss at the Esses (1962)

Photo: Courtesy Garth Greenan

9. Nicholas Krushenick at Garth Greenan, through October 11

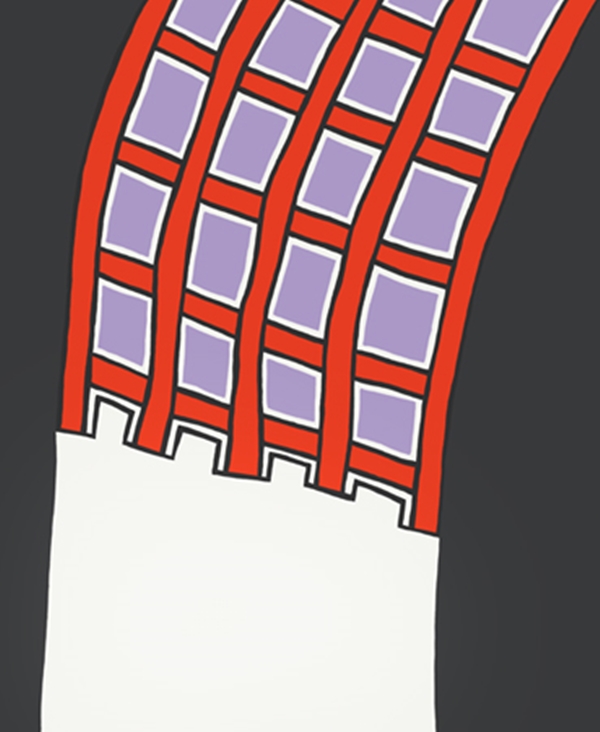

Nicholas Krushenick’s brassy and bold hard-edge abstractions are looking better all the time, especially the early works from the 1960s, which are featured in this lively show. Anticipating a full-scale museum retrospective of the artist’s work, set to debut at the Tang Museum in Saratoga Springs, New York, February 2015, this exhibition, titled “Early Paintings,” includes eight large-scale paintings as well as 10 smaller studies for an untitled 1961 composition, also on view, which Krushenick regarded as his first mature work.

The New York artist (1929-1999) is credited with spawning an offshoot of the Pop art movement dubbed “Abstract Pop,” but the genre fizzled by the mid 1970s, with the advent of Minimalism and Conceptualism. Krushenick’s garish colors and schematic compositions quickly fell from art-world favor. The works seem exciting and relevant again today, thanks in no small measure to the preeminence of computer graphics in the present digital age. Works such as Horizontal Stripes (1963), with its jagged bands of red and yellow colliding against a black ground, and Rousseau Giving Love and Lions (1962), with its undulating pattern of overlapping green bands, seem to be the result of some topological imaging program—nothing if not futuristic.

Prune Nourry, Terracotta Daughters (2014)

Photo: Courtesy China Institute

10. Prune Nourry at China Institute, through October 4

French artist Prune Nourry is known for elaborate installations centered on the theme of bioethics. For this must-see exhibition, a collaboration with the Alliance Française and China Institute, she worked in China for a year and a half to produce “Terracotta Daughters.” These 108 life-size ceramic female figures mimic the famous “Terracotta Warriors” produced in Xi’an in 210-209 BCE, buried with Quin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, and discovered in 1974. Nourry worked with Xi’an artisans, who actually produce copies of the ancient artifacts to sell to collectors and tourists, to make body casts of young volunteers.

The “Daughters” stand upright in this raw, industrial-looking space, lit by bare light bulbs hanging from overhead wires. Arranged in neat rows, like the Xi’an “Warriors,” the figures wear modern clothing and hairdos, and each has an individualized face and expression. In this ambitious work, Nourry, 29, comments on gender preference and demographic imbalance in China. Also on view in the show are a number of related pieces for sale, including bronze sculptures and works on paper. Part of the proceeds of this unusual exhibition will go toward the education of some of the girls who served as models for the “Daughters.”

David Ebony is contributing editor of Art in America, and a longtime contributor to artnet.