California Light and Space artist De Wain Valentine, known for his innovative use of industrial plastics and resins in fine art, has died at age 86. News of his death was confirmed by Almine Rech, the gallery that has represented the artist since 2014.

“De Wain was a pioneer of the Light and Space movement,” Almine Rech wrote in an email to Artnet News. “We were very close; he was the most generous and wonderful person I’d ever met, as well as his wife Kiana Valentine.”

Born in Colorado in 1936, Valentine began his experiments with resin as a middle schooler, after a teacher exposed him to the material and he saw how it could be sanded into smooth, polished surfaces.

“I used to cook them in Mom’s oven and when she came home she’d have a fit and say, ‘You are going to kill us all, you’re going to poison us all,’ and yadda, yadda, yadda,” Valentine told the Brooklyn Rail. “So I’d just open the doors in the middle of winter until the house cleared out.”

De Wain Valentine, Amber to Gold Circle (1971). ©De Wain Valentine. Photo by Matt Kroening, courtesy the artist and Almine Rech.

When Valentine attempted to break into the New York art world in 1961, he found resistance to the medium, with dealers insisting plastic had no place in art galleries.

Meanwhile, Valentine focused on teaching, eventually becoming head of the art department at the University of Colorado, Denver. He made the move to the West Coast in 1965, for a job teaching a course in plastics technology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

“Then I got fired—twice—for teaching the art students how to use plastics because the old guard preferred the smell of oil paint,” Valentine told the Rail.

But Valentine stayed, becoming part of the burgeoning Light and Space movement, also described as the L.A. Look and Finish Fetish.

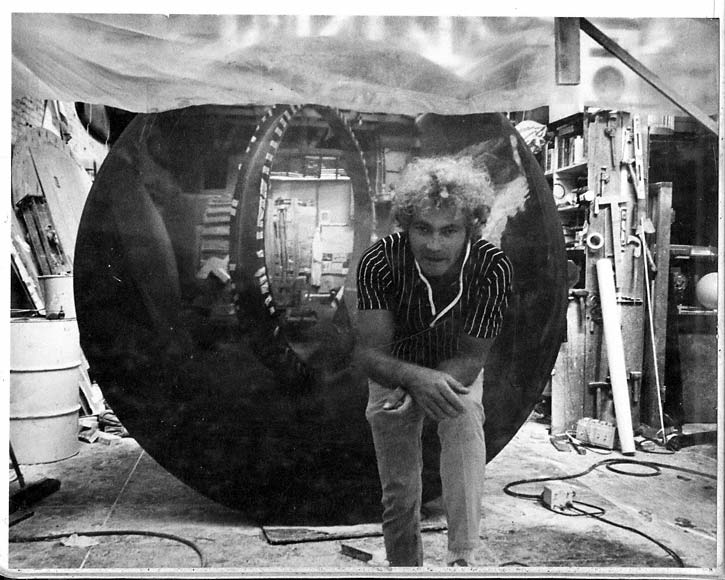

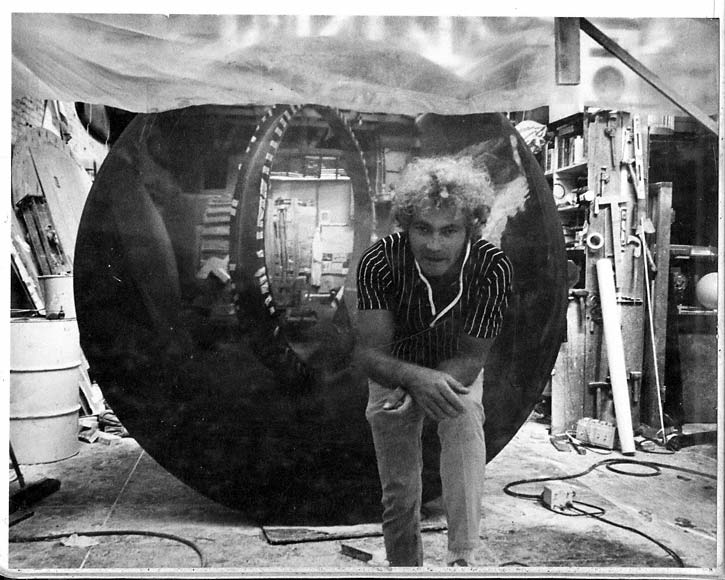

De Wain Valentine in his Venice studio with one of his eight-foot Circle polyester pieces (ca. 1970s). Artwork ©De Wain Valentine. Photo by Harry Drinkwater.

“When I came to California I fell in love with the sky and the ocean,” Valentine said in a 2018 talk at David Zwirner Gallery, crediting the landscape as a major source of artistic inspiration. “I always wanted to have a magic solid so I could cut out a big piece of sky or a big piece of ocean.”

Valentine’s sculptures “reflect the light and engage the surrounding space through its mesmerizingly translucent surfaces that arrest one’s gaze,” art historian Joachim Pissarro wrote in a 2017 Almine Rech Editions catalogue. The work “established him as the technician par excellence in the material, casting two-ton jewels of weight and light,” art critic Peter Plagens wrote in Sunshine Muse: Art on the West Coast, 1945–1970.

In order to create these large-scale sculptures in a single pour, Valentine worked with Hastings Plastics Company in Santa Monica to develop his own polyester resin, patented as Valentine MasKast Resin (existing varieties were prone to cracking when cast at volumes over 50 pounds0.

“Thi s allowed him to build his sculptures to the colossal scales he dreamed about. It was a major scientific feat for any artist at that time, which is still used and appreciated today by artists who followed his path,” Rech said.

Installation view, “De Wain Valentine: Works from the 1960s and 1970s,” featuring Two Gray Columns at David Zwirner, New York in 2015. Photo ©2015 De Wain Valentine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Valentine had a solo exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1979, but only in recent years have his contributions gained more widespread appreciation.

In 2011, Valentine was among the artists whose work was revisited in the Getty’s “Pacific Standard Time” initiative, in the Getty Center exhibition “From Start to Finish: De Wain Valentine’s Gray Column.” The show spotlighted a single work, Gray Column, a 12-foot-tall monolith weighing in at a massive 3,500 pounds.

“Gray Column succeeds in evoking that sense of the sublime that many Light and Space artists were after, but only a few achieved,” curator Kristina Newhouse told Easy Reader and Peninsula, calling the work “a true technological feat given the particularities of cast resin.”

De Wain Valentine polishing Gray Column (1975–76), in his studio. ©2015 De Wain Valentine/Artists Rights Society (Ars), New York/courtesy of David Zwirner.

The sculpture is actually one half of Two Gray Columns, a pair of works Baxter Travenol Laboratories commissioned the work back in 1975 for its corporate headquarters in Deerfield, Illinois.

But the architects ended up lowering the building’s planned 25-foot ceilings to just 12 feet during construction, and the two works had to be displayed on their sides, rather than standing upright. When one got knocked over, the company feared a potential lawsuit, and took them down, eventually returning them to the artist.

De Wain Valentine studio, Venice, California, 1968. Photo by De Wain Valentine, ©De Wain Valentine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2015; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

After “Pacific Standard Time” brought renewed attention on Valentine’s work, the two sculptures were finally reunited in a public exhibition, orientated in the way the artist intended, at New York’s David Zwirner gallery in 2018. It was Valentine’s first solo show in the city since 1981. Another exhibition, “Works from 1967 to present,” followed at Almine Rech the following year.

Valentine’s work is held in the collections of institutions including LACMA and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The artist’s record at auction is $175,000, set in 2015 at Los Angeles Modern Auctions for the six-foot-tall cast polyester resin sculpture Blue Slab (1970), according to the Artnet Price Database.