The major exhibition “Cy Twombly” opened this week at Centre Pompidou with 140 works of art, including drawings, sculptures, paintings, and photographs that have been thoughtfully brought together by curator Jonas Storsve. The hanging of the exhibition is broadly chronological, and blissfully uncrowded; visitors would be advised to allow plenty of time to fully experience the works included.

One of the best things about the extensive show is the opportunity to explore Twombly’s artistic development. The exhibition opens with four intense early canvases from the Foundation Cy Twombly: Volubilis and Quarzazat along with two untitled works. These works were produced in 1953 and inspired by Twombly’s post-Black Mountain College trip to North Africa with Robert Rauschenberg. (Coincidentally or not, London’s Tate opened their major survey of Rauschenberg almost on the same day).

It is remarkable how powerfully these early works pulsate and vibrate with the intense energy that the artist invested into them almost 70 years ago and it is easy to see why his professor, Robert Motherwell, said “there is nothing to teach him.”

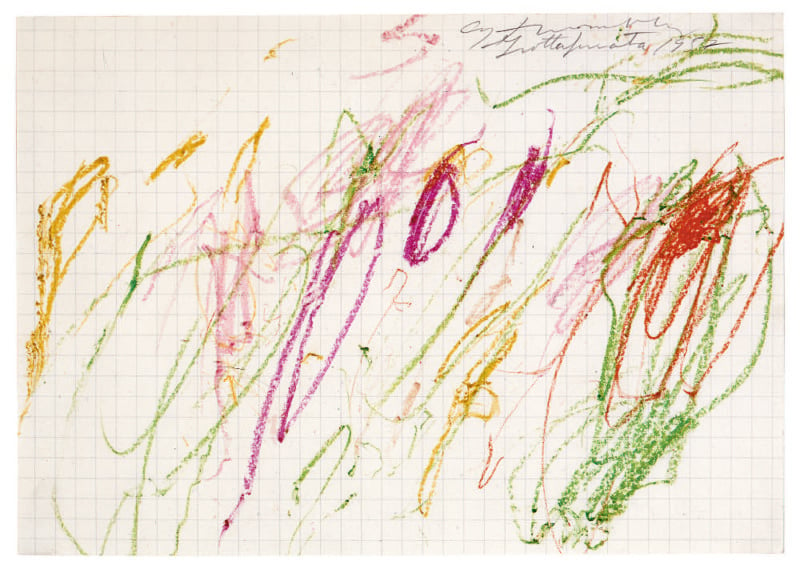

Cy Twombly’s singular expressive approach was defined, clear and present even at the beginning of his career and Freewheeler, from 1955, is particularly interesting. Gestural abstraction and transformative graphical expression—it’s all there, along with layering and expressing his energy through scratching shapes. The use of words and an allusion to language, as well as occasionally removing elements or covering them up, add additional layers of meaning.

Cy Twombly, Night Watch, (1966). Courtesy Jeffrey Hoffeld Fine Arts, Inc. @Cy Twombly Foundation, ©Courtesy Cheim & Read

Twombly rarely discussed his method and curiously never permitted anyone to watch him work. It took days or weeks of building up the energy to paint, countless packets of cigarettes, hours gazing into the middle distance, and many books of poetry (he liked Keats and the later romantics) before he picked up his brushes.

In a rare self-description, he once said, “Each line is inhabited by its own history, of which it is the present experience, it is the event of its own materialization.”

It is also fair to say that it took a while for people to understand his work. As late as 1959, when he had signed with Leo Castelli and entered into what would become one of the most rewarding dealer-artist relationships, he produced a group of 10 paintings for his first one-man show. Commonly known as the “Lexington Paintings,” these works—included in the exhibition—are now clearly recognized as works of pure genius and are almost priceless. However, at the time, Castelli rejected them stating to his young artist that he could not possibly exhibit them as he “did not know what they were.”

And so it went on. Soon after this, Twombly returned to Rome, where he married his aristocratic wife Tatiana and they moved to the palatial apartment in Via Di Monserrato. The grandeur and style of their home was later immortalized by Horst P. Horst, and the stacks of canvases seen in his memorable photographs of grand interiors is the stuff of art-lovers’ dreams.

Here, and later at the studio he rented on Piazza del Biscione, Cy Twombly produced some of his most magnificent and monumental works. His output was prolific, the works were fluid, his creativity poured forth onto canvas. The proportion and grandeur of the work was inspired by his high-ceilinged home, his elegant surroundings, and the color and energy of Rome. Paying homage to the great masters, exceptional examples from this time are exhibited here and include The School of Athens and School of Fontainebleau.

After the death of John F. Kennedy in 1963, Twombly’s work reflected the times more directly. The artist continued to channel his emotion through classical themes, culminating in the production that same year of the now-legendary works Nine Discourses on Commodus.

Cy Twombly, Untitled (Bacchus), (2005). @Cy Twombly Foundation, Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection ©BKP, Berlin. RMN-Grand Palais / Image BStGS

The title refers to to different episodes in the life and death of emperor Commodus. Painted on a grey ground, they express anxiety with an intensity matched only by their beauty. This series is chronologically related, as one canvas follows the next. The emotion is conveyed in color, from pure white to visceral shades of red, pink, burgundy and, finally, yellow—perhaps for putrefaction. The paint is applied in a tight but characteristic circular pattern and the canvasses express this tragic story with powerful simplicity. Needless to say, they are a high point of the exhibition.

Looking at these magnificent works it is hard to believe that when they were exhibited at the Leo Castelli gallery in 1964 they were subjected to fierce criticism by Donald Judd and rejected by contemporary critics. They were all unsold and achieved an almost cult-like status by their conscious absence: they were only shown three times before being bought by the Guggenheim in Bilbao, and have left a great impression on artists as diverse as Joseph Beuys, Eva Hesse, Brice Marden, Richard Serra, and Paul Thek.

Installation view of Nine Discourses on Commodus, (1963). Guggenheim Bilbao Museo, Bilbao ©Cy Twombly Foundation, Rome, ©FMGB Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa, 2016

In the catalogue, art historian Nicholas Cullinan writes brilliantly about Judd’s condemnation. This rejection has to be seen within the context of the American art movement of that time and the other artists in Castelli’s legendary stable. Judd’s rejection of this grand series—which not everyone could read, and was produced by a pseudo-aristocrat with classical aspirations who did not even live in New York—makes sense. Judd was a fierce proponent of the New York scene; Nine Discourses on Commodus is a coeval work of Warhol’s 16 Jackies. Considered this way, it is easy to see which work was more readily available and of the moment.

Twombly returned to New York three years later, with what are now known as the “Blackboard Pictures,” and one year later he finally achieved his first institutional show in Milwaukee. One of the big debates around Twombly is whether he is American or European, and viewing the works in the exhibition you have to wonder if he would have survived and produced the work that he did had he not left for Europe.

Fortunately, he remained in Europe, creating the exquisite works exhibited in this show including Nini’s Painting (1971), The Wilder Shores of Love (1985), The gorgeous Quattro Stagioni (1993-1995), The Coronation of Sesostris (2000), The Bacchus Series (2005), and Blooming (2001-2008).

During the 1970s Twombly was championed by Yvon Lambert, the French gallerist who instinctively grasped Twombly’s genius and exhibited his first solo show in Paris, in 1971. Lambert’s energy, combined with a special synergy between him and the artist, generated enough interest in Twombly’s work to bring about an exhibition of works on paper at the Musee d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1976. Lambert also, wisely, brought the artist together with Roland Barthes, who wrote magnificently and intelligently about his work, finally translating Twombly’s “language” into something people could understand.

As you leave the exhibition and gaze out past the outline of Twombly’s sculptures shown in relief against the magnificent Parisian skyline, these images linger, and irrevocably enter your memory. Whether by coincidence or careful curation, the powerful visual association between the city and this great artist will remain.

“Cy Twombly” is on view at Centre Pompidou, Paris from October 30, 2016 – 24 April, 2017.