Art & Exhibitions

What Does Democracy Look Like? How Political Trauma Can Be Turned Into Artistic Action

A sweeping exhibition at the National Gallery of Greece looks at how history can provide a roadmap for our present political moment.

A sweeping exhibition at the National Gallery of Greece looks at how history can provide a roadmap for our present political moment.

Vivienne Chow

With a record number of countries holding elections in 2024—including the U.S., where Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are battling it out for the White House this week—the future of democracy feels more at stake than ever. At the National Gallery of Greece in Athens, the so-called birthplace of democracy, a sweeping show looks at the history of the government system that is meant to bring power to the people. It is also a roadmap for navigating our present political moment.

Staged to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the restoration of democracy in Greece, “Democracy” is an ambitious exhibition that is billed as the first to examine how artists captured the quest for democratic rule in Greece, Spain, and Portugal during the 1960s and ’70s. The result of two years of research by Syrago Tsiara, the curator and director of the National Gallery of Greece, the show highlights 140 works by 55 artists. But it is more than just a historical exhibition looking into the evolution of political art, according to Tsiara.

Installation view of “Democracy,” “Facing the Enemy” chapter, featuring Yannis Gaitis’s sculpture Five or Six. Photo credit Stavros Psiroukis © National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum.

Instead, the exhibition “helps us to realize, understand, and decode the experiences that we live in nowadays [so that] we can become critical citizens and critical thinkers,” she said, noting that extremist voices have been on the rise around the world while voter turnout in many countries has declined amid the public’s growing skepticism of institutional credibility. “[This show] serves as a poignant reminder of the ongoing need to defend democracy.”

Another mission of the exhibition and her role, noted Tsiara, is to propagate what is known as “sentimental education,” a term some literature aficionados might recognize from Gustave Flaubert’s 1869 novel of the same name. The phrase refers to developing a refined understanding of emotions, ethics, and aesthetics—an “education of the heart” that goes beyond emotional intelligence.

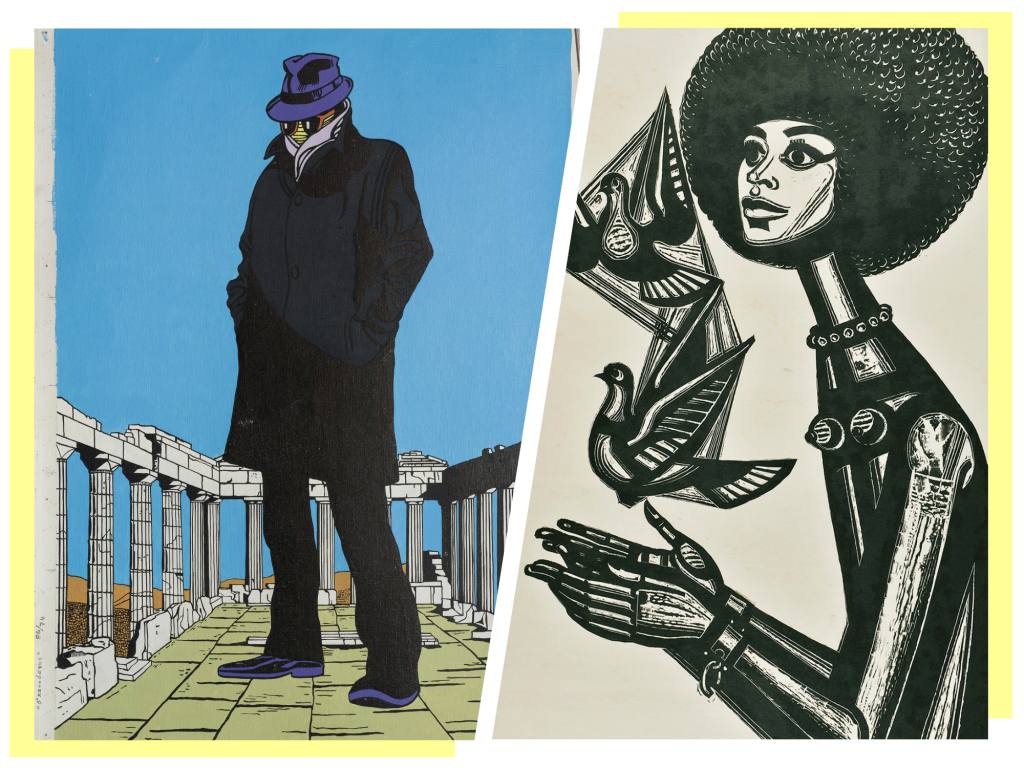

Giorgos Ioannou, Protest at the polytechnic … Athens 17/11/73 B (1973). Photo: Thanos Kartsoglou/Giorgos Ioannou Collection Archive.

For Tsiara, it’s about cultivating a deeper, more nuanced way of seeing and valuing the world so that we can see ourselves and our current struggles as part of something larger. “Sentiments have history, too,” she explained. “The way they have been expressed is very interesting for us to explore, because we don’t know how to deal with our feelings, how to express them.”

Many of the works in “Democracy” respond to a specific series of events that transpired between July 20 and July 24 in 1974, when the Turkish invasion of Cyprus led to the fall of the military junta that had placed Greece under dictatorship rule for seven years. Former prime minister Konstantinos Karamanlis then ended his self-imposed exile and returned to Athens afterwards, leading the country to transition to democracy. The same year also saw the bloodless coup that ended the 40-year long Estado Novo fascist dictatorship rule in Portugal. Spain also began its transition to democracy the following year after the death of Francisco Franco, the military dictator who ruled the country as a dictator from 1939 to 1975.

Reflecting on this powerful political moment in Europe, the show brings together historical works from institutions such as Spain’s Reina Sofia, Museu d’Art Contemporarni de Barcelona, Centro de Arte Moderna Gulbenkian, Centro de Estudos Multidisciplinares Ernesto de Sousa, as well as private collections in Greece and Portugal. Together, the artworks map the emergence of artistic movements and art forms utilized by artists to illustrate social upheaval, such as critical realism and abstract art as well as performance and conceptual art.

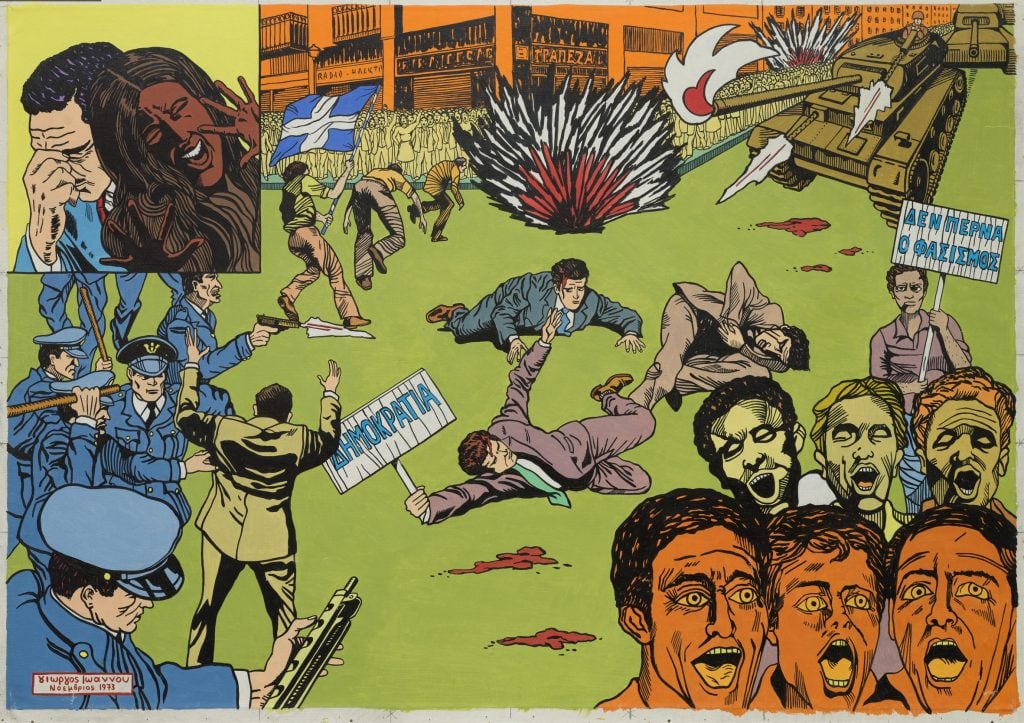

Giorgos Sikeliotis, Angel Warrior (1976). © National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum

Photo Credit: Stavros Psiroukis

The exhibition is organized to chart the emotional journey many experienced in the pursuit of civil liberties and democratic rule. These feelings are categorized into four themes: “Facing the Enemy,” “Resistance,” “Uprising,” and “Arousal.” While the joy of being able to gather and express opinions freely following the collapse of the military regime was apparent in the era in the second half of the 1970s, the trauma of dictatorship was still haunting Greek society, a sentiment that was difficult to express, Tsiara noted.

“Facing the Enemy” highlights works that capture the impression of figures representative of the authoritarian regimes, such as Colombian artist Fernando Botero’s depiction of a bloated Franco (1986). Murdering Freedom or The Colonels (1968), a canvas work by Greek artist Yannis Gaitis, depicts a group with nearly identical faces dressed in military uniforms pointing their guns at a pigeon, a symbol of freedom, illustrating not only what the country was going through at the time, but also the mechanism of control and dehumanization under an authoritarian regime. Jannis Psychopedis, also from Greece and a key figure of the critical realism movement, portrayed political figures in his monotone oil canvases.

Fernando Botero, Franco (1986). @Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Photo: Joaquín Cortés / Román Lores.

The “suffering body” plays a part in the subsequent section, “Resistance,” as a metaphor for the dictatorship experience of torture and repression. Wood cut work on paper In Memory of Che Guevara. The Dead (1968) by Greek printmaker Tassos (Anastasios Alevizos), for example, depicts Guevara, the Cuban revolution leader who was executed in 1967.

“Resistance is an attitude,” Tsiara noted. “Here, Guevara is depicted as the body of the dead Christ. The iconography of the church becomes political art, and martyrs of the dictatorship become the new saint.” Photography works capturing the environment of the Athens-born performance artist, Maria Karavela, whose performance exhibitions depicting bodies tormented by teh regime were censored and shut down.

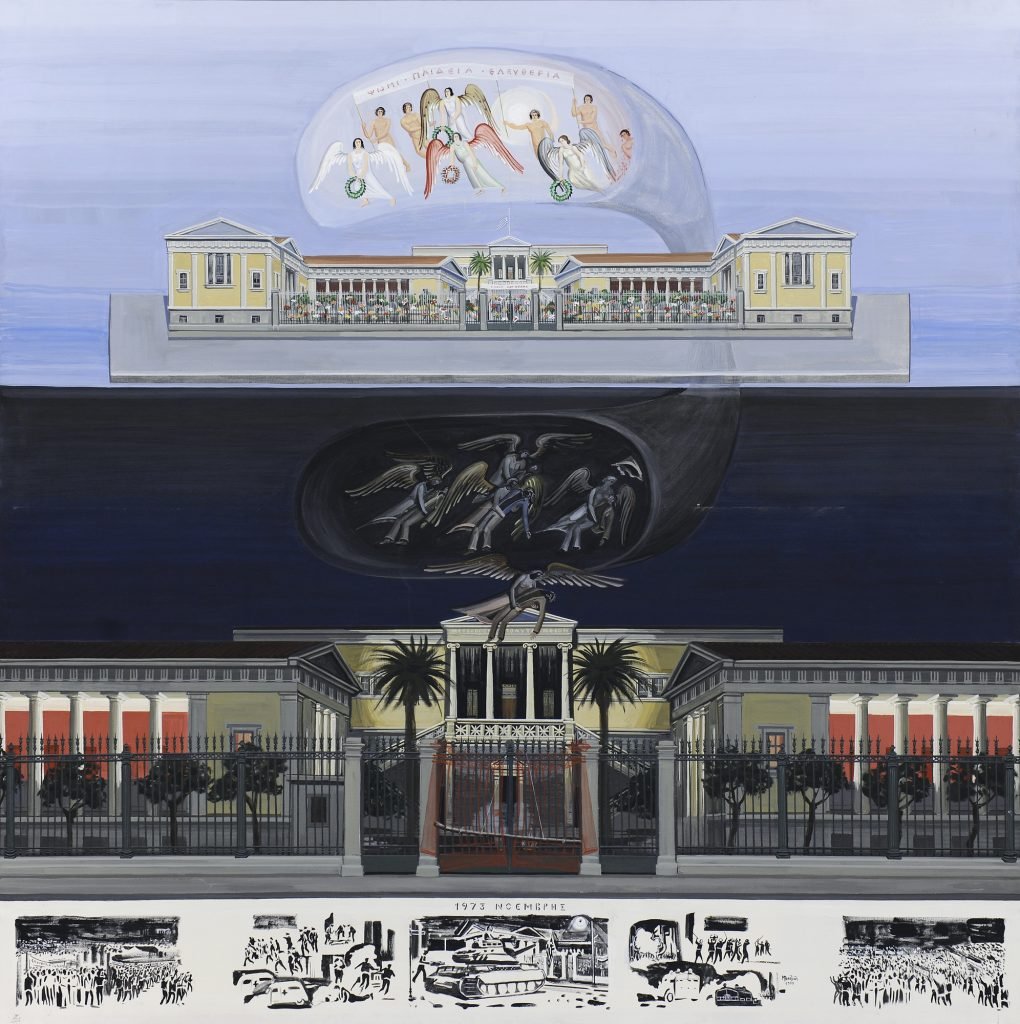

Marios Vatzias, National Technical University of Athens (1975) © National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum. Photo Credit: Stavros Psiroukis

“Uprising” features Revolução, a key video work by Portuguese artist and writer Ana Hatherly who captured the streetscape of Lisbon full of graffiti and posters with a Super 8 camera following the Carnation Revolution, which ended the 50 years of dictatorship in Portugal in 1974. Tsiara said the element of sound plays an important role in not just Hatherly’s work but also in the works chronicling the political struggles throughout this period. The work was first exhibited in Portugal’s participation of Venice Biennale in 1975, a remarkable gesture to illustrate its importance as “a national representation of the country,” she added.

This opposes Marios Vatzias’s complex painting and Manolis Tzobanakis’s sculpture, which reflect on the events 1973 Athens Polytechnic uprising, the student-led protest against the Greek military junta that ended up with very different outcome. The crackdown saw the junta’s tank crushing the gate of the campus killing those inside. It also caused the death of 24 civilians outside the campus and hundreds injured. “We have all this anger, all this pain for the lost bodies, the pain for the students and those who lost their lives in the uprising,” the Tsiara said.

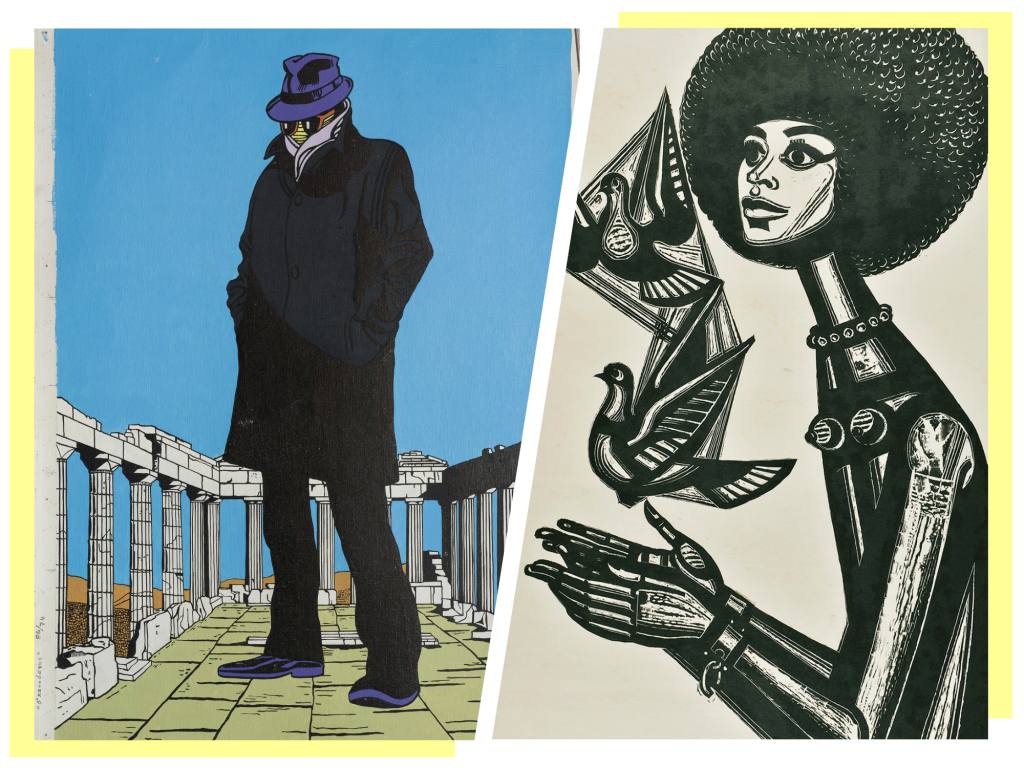

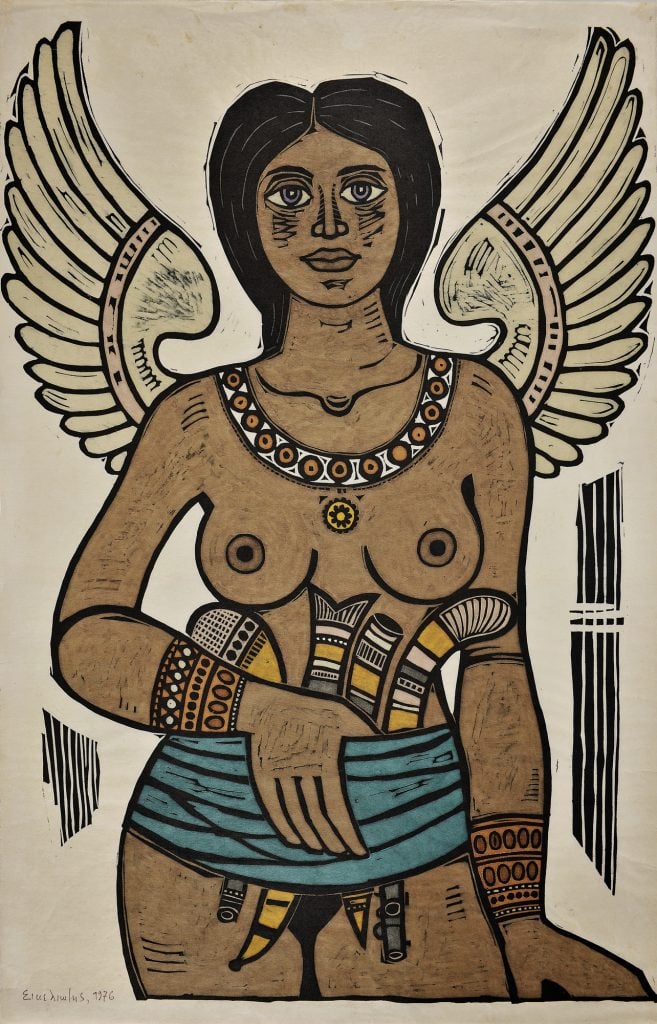

Yannis Gaïtis, The Bird (1971). © Irene Panagopoulos. Photo: Thanos Kartsoglou.

The exhibition concludes with “Arousal,” featuring works that deal with the underlying trauma and grief that coexist with the joy of liberties and the reclamation of the lost voice brought by democratization, such as Pop works by Portuguese painter Nikias Skapinakis, and the surrealist drawings of Portuguese-British artist Paula Rego.

This politically-charged exhibition also poses questions about the nature of political art and the artistic value of creative expresses conceived in response to socio-political challenges. So, what makes good political art?

“There is good and bad political art, just like good and bad performance or oil painting,” Tsiara said. “It’s not just about one work or one project. To me, it is important that an artist does not work in isolation, following and searching only for his or her own existential anxieties. Art is a social practice, so it is political.”

“Democracy” runs through February 2, 2025, at the National Gallery of Greece, Athens.