Politics

The #MeToo and BLM Movements Transformed French Art Schools. But Some Say They Have a Lot Further to Go

While there is certainly new awareness, more concrete actions must be taken.

While there is certainly new awareness, more concrete actions must be taken.

Devorah Lauter

The climate was tense in Paris in 2017, following news of several individual terror attacks on French landmarks, aimed at security officers. But that didn’t prepare one 22-year-old student at a prestigious art school in Paris from being perceived as a threat by his professor because of the color of his skin.

“The professor asked me if I was Muslim, and whether I was capable of a similar act [of terror] at the school. I was shocked. He said other professors were wondering too,” said the artist, referred to as Samuel. He was the only Black student in a class of 70 and commuted from a low-income Parisian suburb to the school known for its homogeneous, upper-class student body. “It was very violent for me,” he said of the experience.

Samuel dropped out and never went back to finish his degree. After three years “of being treated differently because I was Black,” he had had enough. It was a fact which also carried into how his work was interpreted, which was mostly seen through the lens of race. “I tried to make art they wouldn’t assume was all about my [racial] background, but that was impossible,” he said. Barring a few teachers who kept him going, he added the climate was “very limiting and exhausting,” and that it ultimately blocked his ability to create work.

He is not the only one. Artnet News spoke to five students and recent graduates in France from three different art schools about forms of discrimination they directly experienced as students, including sexual harassment, and how those dynamics may have ricocheted into career obstacles. Ten current art students from the same schools additionally spoke to Artnet about their views on the topic, and what their scholastic experience has been like.

What became clear is that, rather than functioning as safe havens, art schools were often marred with instances of discrimination and sexism. Nevertheless, many of those interviewed felt that while much was still left to be done, there is a new awareness around the problem and that student-led initiatives created in the wake of the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements have sparked positive change.

Sophie Vela, who is 23 and a student at the Ecole Européenne Supérieure d’Art de Bretagne in Rennes, said the contradictory nature of liberal art education and abuse can mask the issue. “You think of art schools as open-minded places. And they can be, but that is not incompatible with forms of violence;” she said. “On the contrary, it can camouflage it.”

Protesters during a demonstration called by feminist movements in front of the city hall in Paris, on July 10, 2020. Photo Mehdi Taamallah/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

Vela and two other art students created an online initiative called Les Mots de Trop in late 2019 after one professor allegedly sexually harassed them on several occasions—he is the subject of an ongoing administrative investigation, according to the school. The trio boycotted the professor’s class and launched their platform, which documents discrimination recently experienced in French and some Belgian art schools. Offensive remarks are then printed and hung in schools around the country. “As words flooded our mailboxes, we started to realize the magnitude of the issue,” said Vela. They have received more than 400 testimonials.

Les Mots de Trop was formed after its founders felt their complaints were “not being heard by the school administrations,” according to the group. The school denied this allegation, noting the director at the time “looked for tangible elements that could have permitted the start of a procedure addressing this teacher, but she could not gather a single element at the time.” Later, additional evidence permitted the school to take further action.

Screenshot of the website Les Mots de Trop. Courtesy Les Mots de Trop.

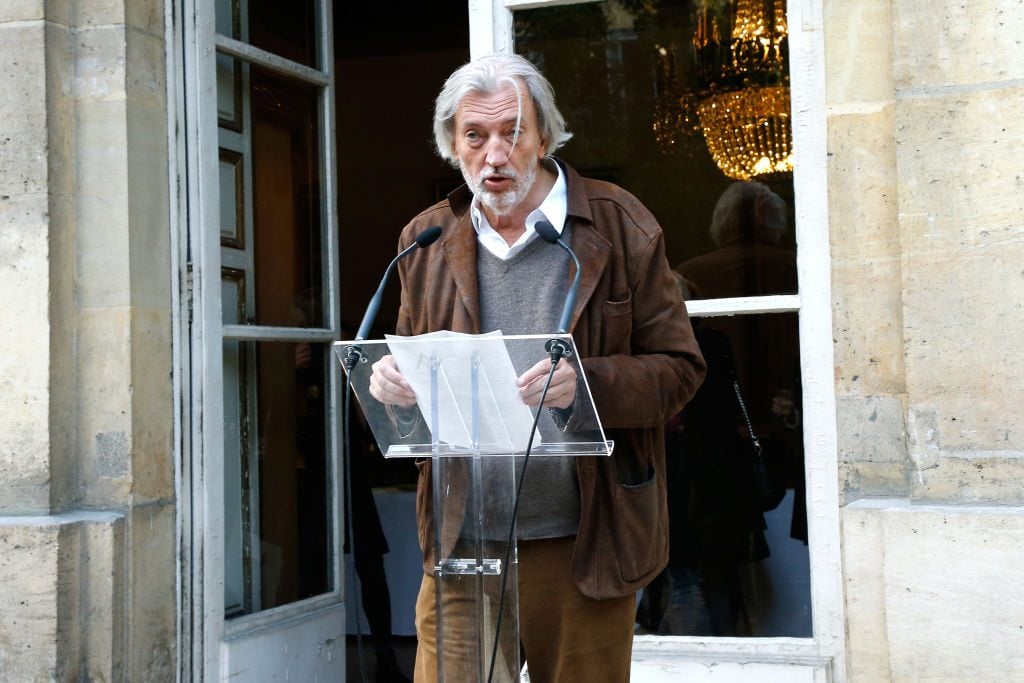

A sense of dismissal was also the case for a 2018 incident now seen as a turning point in France, when students at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris hijacked a school ceremony to protest then-director Jean-Marc Bustamante’s alleged “total absence of consideration for repeated alerts of harassment by professors towards students,” according to one student at the time. Students doused the director with flour and launched a petition condemning the school’s inaction. They also created their own support hotline. The director stepped down that year, though the reasons reported for this are varied.

The historic Paris school has made important changes since 2018, including hiring of new staff. Like many other art schools in France, a “listening center” was established to gather testimonies from victims, and its first woman director, Alexia Fabre, began her job in March 2022. According to one student, there is still room for improvement: “Things are a lot better, but there’s still more that can be done.”

Former director of the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts, Jean-Marc Bustamante. Photo: Bertrand Rindoff Petroff/Getty Images.

The problem is of course not unique to French institutions or art education—discrimination and sexism occur on campuses all over the world. But the less formal, closer personal relationships between art teachers and students, common at such institutions, can blur the lines between what is appropriate versus inappropriate behavior, according to Vela, school administrators, and researcher Mathilde Provansal, a postdoctoral fellow in sociology at LMU Munich, Germany.

That dynamic is set within a context where those same, closer relationships play an outsized role in how artwork is judged, and teaching is conducted. Additionally, student work, which is often of a personal nature, can leave their creators in a particularly vulnerable position. It should also be noted that students can be the aggressors, and that teachers can also suffer from abuse by their superiors or colleagues.

Sexual harassment and sexism, as well as other forms of discrimination in art schools, have been shown to have a harmful impact on art careers, according to Provansal. Her research backs the notion that art schools are in many ways at the heart of inequalities seen in the professional art world. Indeed, a majority of art students around the world are women, and yet, as of 2019 women still only accounted for about a third of artists represented by international galleries who participate in Art Basel, according to sociologists Alain Quemin and Kathryn Brown.

After observing a major French visual arts school, Provansal found that female students were less likely to form the informal, yet crucial, mentor-like relationships with professors, and that concerns around sexism and harassment were among their stated reasons. Women who changed classes to “escape a student-professor relationship based on seduction,” were at a “disadvantage,” Provansal told Artnet News, citing research she published in 2018. “It made it harder to build that closer relationship with the professor,” she said, “which is so important for benefiting from his network and career knowledge.”

She also found that racial stereotypes of minorities worked against chances of acceptance at the school. Provansal observed how, on an unspecified date between 2010 and 2017, kept secret to protect the identity of those involved, a faculty-led jury charged with selecting students “ultimately caricatured and limited the artwork [by one applicant of Algerian descent] to an identity-focused reading.” The jury rejected the applicant and suggested she “come back and add more babouches,” referring to traditional North African slippers.

Alexia Fabre, the new director of École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris. Photo: Alain Nogues/Corbis via Getty Images.

Today, more schools have been working towards change. Since 2018, France’s ministry of culture began offering training programs on discrimination in schools and created a free legal hotline. It also required art schools to adopt equality charters. In 2015, the National Association of Higher Schools of Art, a network of French art schools, also federated an anti-discrimination charter. But the charters can also be seen as “performative,” said Vela, the art student.

Indeed, one top French art school which devoted considerable attention to its commission for equality and diversity on its website could not answer Artnet News’s questions about the work it has done, due to having formed only a few months prior. When another school was asked about their hotline for victims of abuse, a press representative asked whether Artnet News’s intentions were “benevolent,” because “everything is fine now.”

Creating “a climate of trust” among students remains a major challenge, said Emmanuel Tibloux, director of the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Like many prestigious schools in the capital, the school lacks diversity. Since his arrival in 2018, Tibloux has initiated several reforms, including adapting the entrance exam. “Creativity often benefits from differences,” he said, noting that the faculty is “still in the majority masculine and very largely white.” He told Artnet News that future hires will better represent France’s diverse population.

Today, “people are speaking up more freely,” as Tibloux put it, with initiatives like the school-supported, teacher and student-run Chères Toutes platform, candidly voicing the experiences of women at the school. Yet resistance remains. “There’s a lot of work still needed to educate older generations, who are slower at getting on the same page, but thanks to students, they’ve been forced to get with it a little [more],” said Marine Multier, in charge of preventing discrimination and sexual violence at La Fémis film school. “There are still people who are clearly not convinced there’s a problem, but with new training programs, we see a real before-and-after.”

“There’s a new level of consciousness today,” said Vela, the art student, who nevertheless asserts most perpetrators keep their jobs with no real consequences. “Not long ago, we were alone. A few years later, about 40 students showed up to a meeting. Also, teachers are paying attention to how they address students,” she added.

With greater awareness, students have been filing more claims, which some administrations also feel unprepared to handle. “It’s very positive that people are talking more about this now. It complicates our lives, but it’s very important,” said Danièle Yvergniaux, the general director of the Ecole Européenne Supérieure d’art de Bretagne. “It’s very difficult for us to evaluate cases. We’re not professionals of this kind of thing. We’re always struggling. Even if we think we’re doing everything we can… We feel like we’re walking on eggs.”

Today, Samuel feels his decision to leave the school was the right one in terms of his creative process, despite losing access to a network of contacts, and never earning a degree. Not long after the incident, he did go back to notify the director about what happened and was offered his spot back. Artnet News contacted the former director about it, but he could not recall the incident and noted that if a complaint was not put in writing, there is little that can be done.

In any case, Samuel said he declined the offer. “At school, my work was extremely structured, so that when I left, I literally exploded. [The artwork] became a kind of chaos that spread and grew, that became brighter and bigger… [Leaving school] was a chance to be myself artistically, to be able to make a work of art and know that it comes from what is deepest within me. Nothing else.”