Art & Tech

What Is the Future of the Digital Catalogue Raisonné? Experts Weigh In

A new initiative by the Rauschenberg Foundation is the latest to bring the catalogue raisonné online.

A new initiative by the Rauschenberg Foundation is the latest to bring the catalogue raisonné online.

Adam Schrader

The Rauschenberg Foundation, dedicated to preserving the legacy of the late Texan artist Robert Rauschenberg, is beginning the task of creating his catalogue raisonné. It will be published online only, making it a relatively new phenomenon in the industry, which has been slow to catch on some three decades after the internet became available to the public.

That being said, it is not the first example to go digital. Researcher Emily Atwater noted the trend in an academic journal article in 2012, more than a decade after the National Gallery of Art launched one of the first pivotal archive projects in 2001.

At the time, Atwater noted the hurdles of transitioning to the web. Many of the issues she highlighted don’t seem to have caused major problems, such as concerns about the authority and authenticity of projects. In recent years, more digital catalogs by major artists have been published online.

Robert Indiana in his NYC studio with his LOVE sculpture, 1969. Photo: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images.

For example, the Sam Francis Online Catalogue Raisonné Project went live in April 2018, as an extension of a printed catalog released seven years earlier. A celebrated digital catalogue raisonné of work by Edgar Degas, developed over 15 years, also went live in September 2019. The most recent project comes from the estate of Robert Indiana, and was authored by the artist’s former gallerist, Simon Salama-Caro. It was released in November 2023 amid legal disputes concerning intellectual copyright.

Jackie Foster, the project manager for the catalogue raisonné at the Rauschenberg Foundation, discussed the challenges her team and others have faced, ahead of the first phase being released next year.

“There is no Rauschenberg catalogue raisonné that already exists. We have a FileMaker Pro database that was used by the artist’s studio while he was working and we’re building that out and adapting it,” she said. “A lot of people start from scratch and have software intended to be used for a CR, but we’re using an existing database and making changes so it can work for a CR purpose.”

Among key differences from other digital catalogue raisonnés is that the Rauschenberg Foundation is releasing it in at least 10 iterative phases over the next 15 to 20 years. The first phase to go live in October 2025 and will mark Rauschenberg’s first five years as an artist, from 1948 to 1953.

“People ask why we don’t publish works as research is completed. The reason is that all CRs reflect the artist they are the subject of, and Rauschenberg worked in series, so it makes sense for us to consider series as a whole, as well as on the individual level,” Foster explained.

Another reason the foundation felt the need to put the catalogue raisonné online was because the artist himself was “super experimental” and loved technology. It was felt that putting it on the web was “very much in his spirit.”

“There’s nothing wrong with print as a technology and there are many beautiful catalogue raisonnés that are print,” Foster said. “But we felt it made a ton of sense. If you want something more flexible, a digital publication seems to better serve the work.”

From Print to Digital

Jane Kallir is the director of the Kallir Research Institute, which took over the library and archives of the largely closed Galerie St. Etienne. It was formed by her grandfather and still represents Sue Coe and Grandma Moses, as well as maintaining an inventory of works by a few other artists.

The research institute is working on updating its Egon Schiele catalogue raisonné, first published digitally in 2018. It was adapted from a print edition published in 1990 and expanded in 1998. Her team is working on making the digital interface smoother, sleeker, and faster, among other updates, she said.

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait with Lowered Head (1912). Leopold Museum, Vienna, Austria. Photo: VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images.

“Schiele is a hard artist to do a catalogue raisonné for if you want to include the watercolors and drawings. It’s no big deal to do the paintings, there’s 300 of them, but when you get to drawings and watercolors, there are like 3,000 of them—which is why this wasn’t done until 1990, even though he died in 1918,” Kallir said.

She noted that Schiele is among the artists whose value has increased enormously since 1990, boosted by provenance research and claims his works were looted from Jewish families by the Nazis in World War II.

“So, we found that an update is sorely needed. We also felt that the cost of making this available in print form is, today, prohibitive. Also, the information is much less widely accessible if you publish a book than it would be if you do it online,” Kallir said.

She hopes the research institute will get all images online with basic descriptive entries of each work by the end of this year, for the second version of the digital catalogue raisonné. “It will probably take us at least another two to three years to update the provenances for all this work,” she said, calling it a “massive undertaking” even though she already had an existing database of Schiele’s work.

“The original book was a 10-year project to gather all that material. So, doing the update might not be quite as overwhelming as the original publication,” she said. “On the other hand, the complexity of the provenance is much greater today than it was in 1990 and there is much more available about provenances today than there was then.”

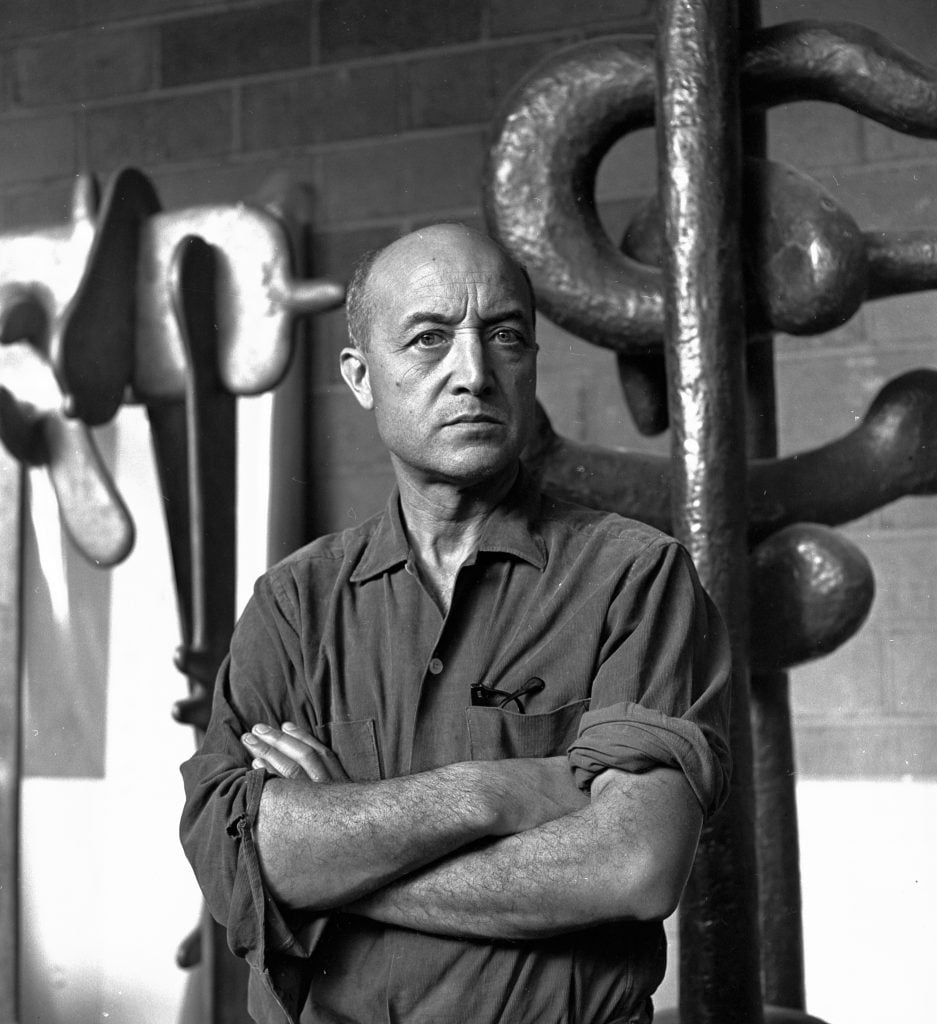

Isamu Noguchi in his studio, 1966. Photo: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images.

The website for the Isamu Noguchi Catalogue Raisonné made similar points in a statement explaining the history of the project. The online publication first launched in 2011 and has gone through multiple updates. Like Schiele’s, this version was based on a printed publication that came before it and benefitted from existing archival research technology.

“The basic issue with the digitizing is the programming, is the software, and the problem with the software is that you can’t really buy anything off the shelf,” Kallir said.

She noted that their research database has been digitized since the 1980s, while everything since then has been specifically customized for Egon Schiele.

“Every artist’s oeuvre is different,” Kallir said. “So, the way that we organize the images for Schiele is probably not something that’s going to work for Rauschenberg—and what they do for him probably isn’t going to work for Cézanne. You need to look at the artist’s work first and figure out what makes sense for them.”

Online Sustainability

Another challenge of putting a catalogue raisonné online is the quickening pace of technology. The internet is a drastically different place from 30 years ago. Because catalogue raisonnés are so labor and time intensive, they need to be sustainable in their online environment for years to come.

“Nobody saw anything wrong with doing this on paper for a long time and there are definitely advantages to having a catalogue raisonné in print. This is perhaps one of the problems with the software, as it is often not as flexible as flipping through a book,” Foster said. “There is a difference between a computer search and a visual physical search and I’m still not sure that the software is quite where it needs to be.”

Still, having a catalogue raisonné online allows it to be used like a true database. A researcher could, for example, search an artist’s oeuvre by motifs or materials used, play accompanying video, see 3D models, and more

However, Foster recognized there will need to be maintenance. Simply putting a digital catalogue raisonné out online and leaving it “could be worse than a print publication.”

There are also issues of quality control to consider. Printed catalogs give more agency to the publishers over the output, concerning things like color correction, which can’t be calibrated for the screen of each person viewing it digitally.

But might artificial intelligence play a part in a catalogue raisonné project? To do so, Foster said, publishers would need to be really confident about their data.

“I am hesitant to engage with machine learning at this stage because if you have bad data, that’s going to affect the results and how you train it,” Foster said. “That’s something that’s very much on our radar. We are reading and learning about it, but at this stage I haven’t found something compelling to convince me it’s a good time to leverage that technology.”

Georgia O’Keeffe outside her art studio in Abiquiú, New Mexico, 1960. Photo: Tony Vaccaro/Getty Images.

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, in its white paper, seemed less timid about the possibilities of artificial intelligence. In January, the museum released a new interactive, data visualization tool that organizes more than 2,000 artworks created by the artist over her lifetime. The museum called it a “step forward” in reimagining her catalogue raisonné, having received a $50,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to explore these possibilities.

“Data extraction may even make other forms of research using data visualization and artificial intelligence more easily achievable, leading to new findings and knowledge,” the white paper read. “Though A.I. uses did not come up in interviews, its emerging ubiquity and power should be considered in the design of the generative digital catalogue raisonné moving forward. A.I. could help reveal connections in the metadata and archival resources while also offering advanced computational image analysis.”

Accessibility and public interest

Because of its applications, digital catalogue raisonnés could foster increased interest among the general public, who are far from the primary audience for printed editions.

“Catalogue raisonnés are really expensive to produce and that intrinsically limits who can access and afford them,” Foster explained. “They also have space constraints on the amount of information they can contain, so they often adopt shorthand. To read them you need the key to decode the abbreviations.”

Foster specifically stated that she hopes the use of “plain English” in the digital catalog will increase accessibility. It will also be available for free, while the foundation looks at ways to add more context, for anyone who wants to learn more.