Art & Exhibitions

A California Museum’s Prized Gauguin Goes on View—But How Real Is It?

The painting was excluded from the artist's recent catalogue raisonné, casting doubt on its authenticity.

When Paul Gauguin’s Flowers and Fruit arrived at the Haggin Museum in Stockton, California, in 1939, the then-fledgling institution had no idea what to do with it. The Haggin, after all, was founded as a historical museum, intended to preserve and showcase artifacts from the region’s early settlers. The donation by its patrons, Robert T. McKee and Eila Haggin McKee, of more than 180 European paintings, then, seemed beside the museum’s civic-minded mission—an afterthought. And though the works were put on view, they were treated as such.

That is, until 1957, when the sale of the French artist’s Still Life With Grapefruits (1901) in Paris realized $255,000. The remarkable sum was enough to warrant an item in the New York Times, which the Stockton Evening and Sunday Record duly picked up. “City Possesses Rare Gauguin,” the article trumpeted, before quoting the Haggin’s director, who said the sale “unquestionably enhanced the value” of its own Gauguin. The institution swiftly promoted Flowers and Fruit from its McKee memorial gallery to its front hall in a special display—newly recognized, per its director, as “perhaps the most costly painting in the museum’s collection.”

Flowers and Fruit to the right of the mantle in the McKee Gallery at Haggin Museum, 1939. Photo courtesy of Haggin Museum.

Today, the Haggin’s prized Gauguin has returned, after a spell in storage, to view in another special display. This time round, there was no sale enhancing the painting’s value; rather, in a stunning turn of events, the work has been excluded from the artist’s most recent catalogue raisonné, casting a shadow on its authenticity. Was the still life a Gauguin to begin with? And if it was, why is it no longer?

Those questions go to the heart of The Case of the Disappearing Gauguin, a new book by art historian Stephanie A. Brown, which occasioned the show. In her biography of the painting, Brown traces the canvas’s journey from Paris to California—through smoke-filled auction rooms, a collector’s ornate salon, and a well-networked gallery in London to become the first Gauguin to land in a West Coast institution. “At its core,” she wrote in her introduction, “this is the story of how one object, one stretched length of painted canvas, passed through the lives of different individuals over the course of a century.”

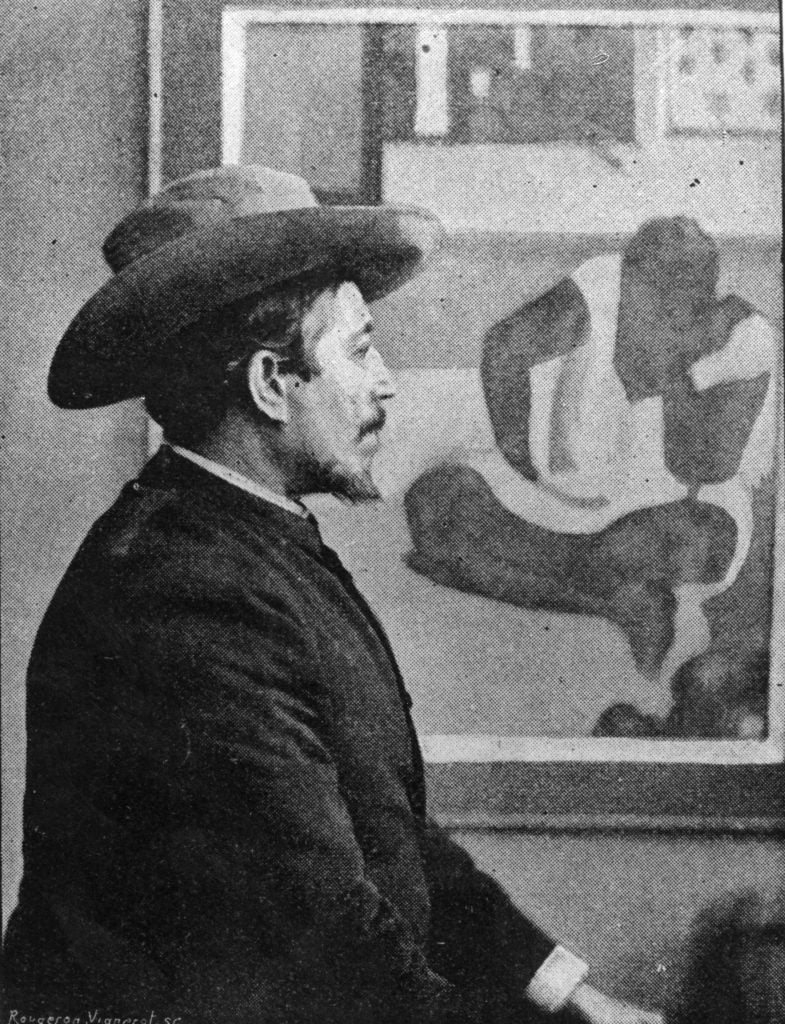

Paul Gauguin seated in front of one of his paintings, ca. 1895. Photo: Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

The undated Flowers and Fruit depicts two vases of roses—one cylindrical and pink, the other deep indigo and plump—sitting on an ochre-colored surface that is scattered with green and red apples. In its bottom-right corner is the inscription, “à l’ami Roy” (to my friend Roy), and the initials “P.G.”

The dedication provided Brown her first lead: Louis Roy, who was in Gauguin’s tight circle of friends and peers. Her deep research surfaces the enigmatic Roy, a painter and art teacher so obscure that historians believed his was merely a pen name or even a hoax. But his very real existence, as Brown found, was often intertwined with that of Gauguin’s: they notably collaborated on a set of prints based on the latter’s Noa Noa woodblocks in the 1890s. Roy was apparently also dear enough to Gauguin to merit the gift of a still life.

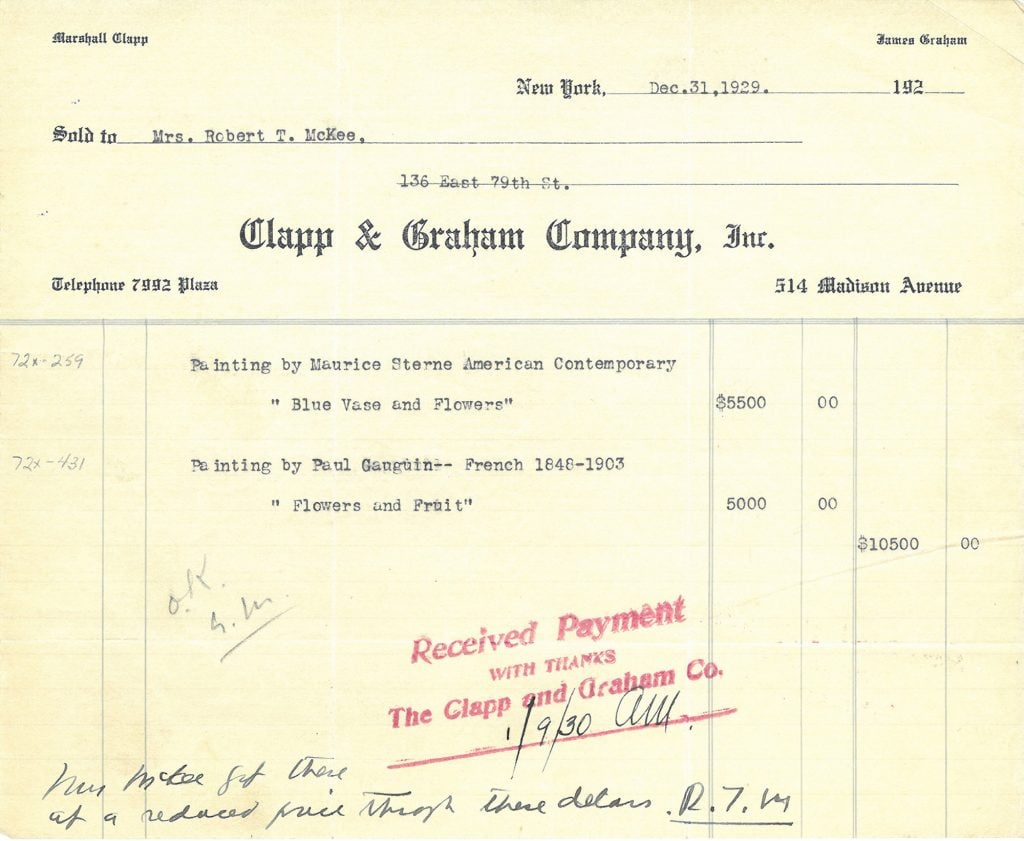

After Roy’s death in 1907 at age 44, his collection was dispersed via auction. Flowers and Fruit would pass through the renowned Hôtel Drouot—twice—and New York’s Reinhardt Galleries before ending up in the collection of the McKees. The couple’s purchase of the canvas in 1929, Brown wrote, was “the first in a chain of events that would make the painting disappear from the international art world.”

The McKees’ original receipt recording the purchase of Flowers and Fruit by Paul Gauguin. Photo courtesy of Haggin Museum.

Her use of the term “disappearing” is spot-on, for the painting wasn’t just taken off the art market with its acquisition, but placed in a museum that did nothing to advance its profile, before disappearing entirely from Gauguin’s official catalogue raisonné.

Here, the story’s undercurrent of cultural power comes into focus. The Haggin directors, Brown noted, networked almost exclusively within the Stockton community, per the museum’s focus. “There is no record of their working with art dealers or art historians to learn more about the museum’s collection,” she wrote. “Their work was about the community and about keeping the museum central to it.” Flowers and Fruit was never sent out on loan or included in any touring shows.

So, when Daniel Wildenstein and Raymond Cogniat were compiling their latest catalogue raisonné—rifling through auction records, exhibition catalogs, and other historical archives—they found close to nothing documenting the painting’s provenance, much less its ongoing existence. “They likely did not know that Stockton existed, any more than people in Stockton knew that the Wildenstein Gallery [in Paris] existed,” Brown wrote.

Of course, neither the exclusion of an object from a catalogue raisonné nor its disappearance from the art market negate its authenticity. But Brown is more concerned with how value is defined and determined by the art world, and how a painting’s journey between the realms of the market and museum could radically transform how it is appreciated.

Installation view of “The Case of the Disappearing Gauguin” at Haggin Museum. Photo courtesy of Haggin Museum.

The new exhibition at the Haggin also includes the results of recent scientific analysis on Flowers and Fruit, which did in fact find the canvas accords with what was used in France in the late 19th century. They are revealed alongside documents illustrating the painting’s trip from Paris (including the McKees’ purchase receipt) and prints of Gauguin’s similar still lifes.

The viewer is left to decide, according to the museum’s press release, “what constitutes authenticity.” More meaningfully, they are invited to observe a work suspended between realities, with an incomplete history, its disappearing act just the tip of its story. The canvas “continues to exist in limbo,” Brown noted. “It is at once rooted in its historical connections and adrift from its origins.”

“The Case of the Disappearing Gauguin” is on view at the Haggin Museum, 1201 N. Pershing Ave, Stockton, California, through April 6, 2025.