Galleries

Do You Have to Be Rich to Make It as an Artist?

Art students are chasing a dream without understanding how the system works.

Art students are chasing a dream without understanding how the system works.

Ben Davis

On my end-of-the-year “Best Shows” list, I nominated Rachel Rose’s hypnotic Everything and More video at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In response, I received a concerned email from an acquaintance. He agreed that Rose’s work was “entrancing,” but wondered “if production value isn’t a significant part of the enchantment,” pointing out that Rose might have an advantage in this area: She hails from one of New York’s most powerful real estate fortunes.

He wrote that he couldn’t help but feel that her Whitney show was emblematic of a moment in which “more and more cultural space is being occupied by extremely wealthy cultural producers.”

The observation nettled me.

How many of last year’s art highlights, I wondered, were by “extremely wealthy cultural producers”? I went back and scanned through the 2015 museum calendar. It doesn’t take much research to find further examples.

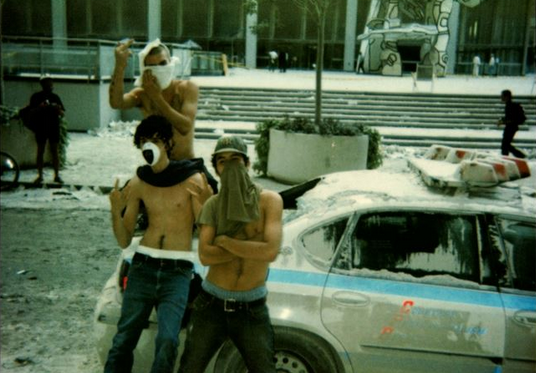

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Geometry of Hope (1976), on view at the Guggenheim from March 13 to June 3, 2015.

Private collection © Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian / Courtesy: Rose Issa Projects / Photo: Courtesy the artist and Rose Issa Projects.

In March, the Guggenheim showcased 91-year-old Iranian artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, whose intricate mirrored works have recently become much-celebrated. According to the Financial Times, Farmanfarmaian had “a privileged upbringing,” from a family of wealthy merchants. Her father was even elected to Iranian parliament. She has, the paper wrote, “enjoyed a life of glamour, exile, return, revelation, parties, and hard work” (presumably in that order).

Yoko Ono, Half-A-Room (1967) on view at the Museum of Modern Art from May 17 to September 7, 2015.

Private collection / © Yoko Ono 2014.

Two months later, MoMA celebrated Yoko Ono’s pioneering contribution to interactive art. Ono’s maternal grandfather founded the massively important Yasuda Bank, and was considered one of the architects of industrial Japan; her father, Eisuke, was himself a successful banker. Given the resulting resources, “one can argue that Ono had been groomed to be an artist from the start,” the Japan Times once wrote.

Rachel Rose, still from Everything and More (2015), on view at the Whitney Museum, from October 30, 2015 to February 7, 2016.

Photo: Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

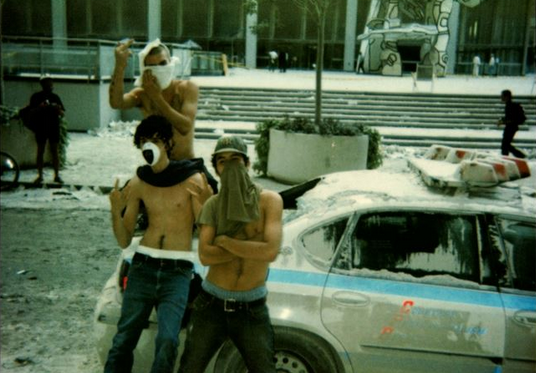

In November, the Peter Brant Study Center celebrated the late Dash Snow (1981-2009), the enfant terrible who helped pioneer the Vice look. Snow was a child of the De Menil clan, “the closest thing to the Medicis in the United States,” as Ariel Levy once wrote in New York. (Also: Uma Thurman was his aunt.)

A well-to-do background tells you nothing about other hardships such figures have had to face or choices they have made. In some ways, the observation tells you very little. Between the relative obscurity of Farmanfarmaian and the household-name status of Ono, or the Dionysian temper of Snow and the brainy bent of Rose, there is not much in common—formally, temperamentally, or otherwise.

Yet there’s actually a point to be made of that fact: Beneath the surface of an otherwise wildly pluralistic art world, family wealth is a connecting thread.

Art is a self-starting, entrepreneurial activity, and what is true of entrepreneurs in general is perhaps true of artists. “[T]he most common shared trait among entrepreneurs is access to financial capital—family money, an inheritance, or a pedigree and connections that allow for access to financial stability….,” Quartz recently explained, debunking the cult of the entrepreneur as visionary risk-taker. “When basic needs are met, it’s easier to be creative.”

Banner image for the study “Panic! What Happened to Social Mobility in the Arts?,” by Create in association with Goldsmiths, University of London, University of Sheffield, and the London School of Economics.

Image: Courtesy Create.

And yet it must be admitted that extreme wealth is not, in fact, the typical family background of a successful artist. In the class-obsessed UK, a survey last year confirmed, as the Guardian summarized it, “Middle class people dominate arts.” I know of no similar study for the United States—but here’s what I know about a few other artists who featured prominently in New York museums in 2015:

Wolfgang Tillmans, Book for Architects (2014), which was on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 26–November 15, 2015.

Image: Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, Maureen Paley, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Galerie Buchholz.

Wolfgang Tillmans’s father was “a traveling salesman and exporter of German tools;” his mother “a politician in the local Conservative party.”

On Kawara’s “Today” paintings, installed for his retrospective at the Guggenheim, March 6 to May 13, 2015.

Photo: Ben Davis.

On Kawara’s father was “the director of an engineering company.”

Pierre Huyghe’s Roof Garden Commission for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 12 to November 1, 2015.

Image: Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pierre Huyghe is the son of an airline pilot, a fact that he often credits for a cosmopolitan worldview.

Work by Sarah Charlesworth, Red Mask (1983) in her retrospective at the New Museum, June 24 to September 20, 2015.

Image: Courtesy New Museum.

Sarah Charlesworth’s father was an engineer and “an executive at Western Electric whose job took the family to different cities.”

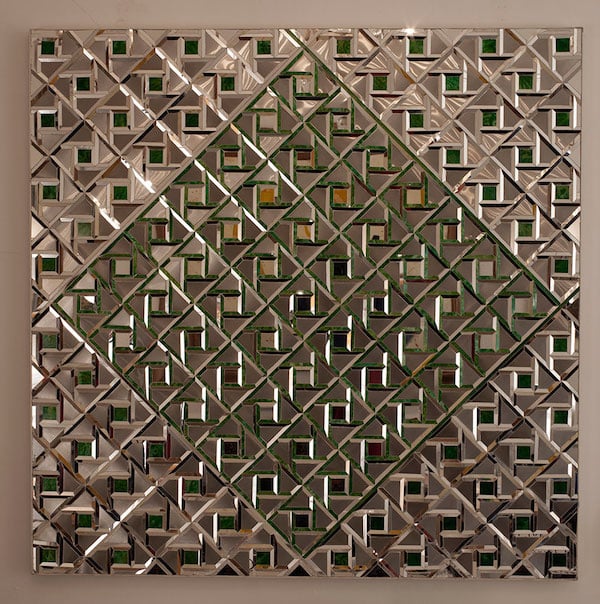

Doris Salcedo at the Guggenheim, June 26 to October 12, 2015.

Doris Salcedo’s father was “a small-businessman;” her mother “supplemented their income by taking in fancy sewing and embroidery.”

Jim Shaw, I dreampt I was taller than jonathan borofsky in his retrospective at the New Museum, October 7, 2015 to January 10, 2016.

Jim Shaw’s mother was a “medical transcriber;” his father “a package designer who then became a CPA.”

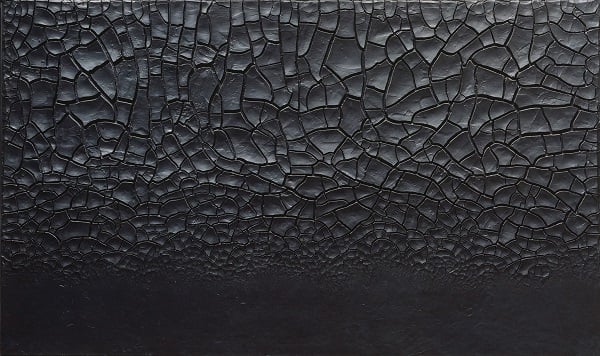

Alberto Burri, Grande cretto nero (1977), on view at the Guggenheim, from October 9, 2015 to January 6, 2016.

Image: Courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum.

Alberto Burri’s father was a wine merchant; his mother taught primary school.

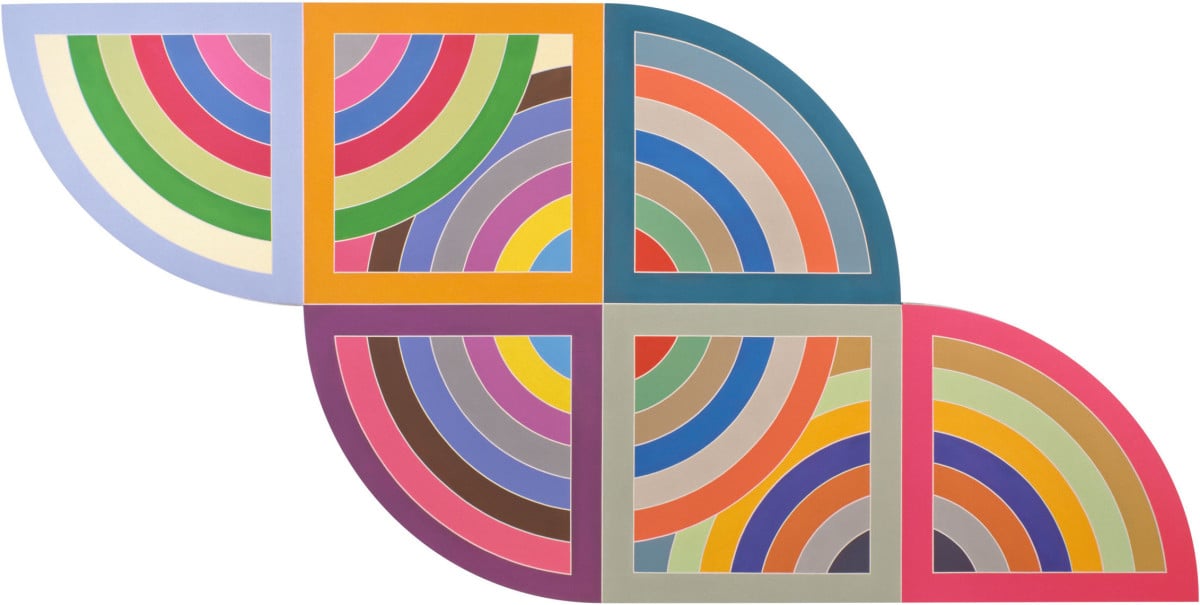

Frank Stella, Harrigan II (1967) in his retrospective at the Whitney Museum, on view October 30, 2015 to February 7, 2016.

Image: Ben Davis Courtesy of the Whitney Museum.

Frank Stella’s father was a gynecologist, his mother “an artistically-inclined housewife.”

Again, an eclectic lot. Yet it does seem that the typical background of a venerated member of the international art scene is roughly in line with the results of that British survey: “[A]n overwhelming majority of respondents working in the arts (76%) had at least one parent working in a managerial or professional (i.e., ‘middle class’) job.”

There are counter-examples to this trend, of course.

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series: Panel 40 “The migrants arrived in great numbers” (1940-41), on view at the Museum of Modern Art from April 3 to September 7, 2015.

Image: Museum of Modern Art © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation / Artists Rights Society / Digital image © Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource.

The legendary Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), whose “Migration Series” at MoMA was also on my end-of-year list, was himself a child of the Great Migration, raised by a hard-pressed mother whom he had to support when she lost her job during the Depression.

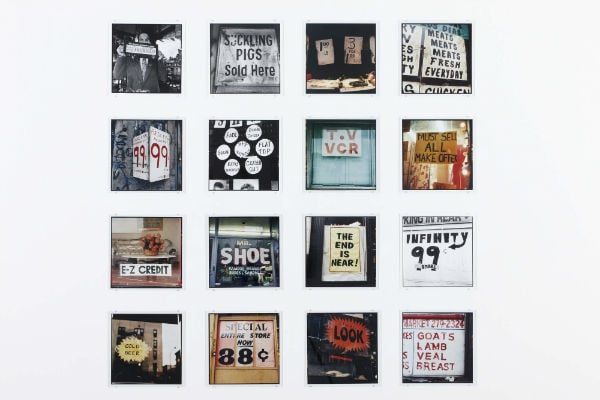

Zoe Leonard, Chapter 17 from Analogue (1998–2009) on view at the Museum of Modern Art, June 27 to August 30, 2015.

Image: Courtesy Museum of Modern Art © 2015 Zoe Leonard.

Zoe Leonard (b. 1961), another MoMA highlight of last year, is the daughter of a Polish refugee. “[W]e were not even working-class; we [were] just really poor,” Leonard told the ACT-UP oral history project.

Installation view of Oscar Murillo’s canvases at “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art from December 14, 2014 to April 5, 2015.

Photo: Courtesy of artnet News.

Oscar Murillo (b. 1986) is too young to have had his own MoMA show, but his paintings were the most–debated aspect of the museum’s “The Forever Now” survey. He’s a prominent example of a contemporary artist whose hard-scrabble background is part of the legend—sometimes to a degree that shows how tone-deaf the art world is when it comes to matters of class (I’m thinking of the Rubells’ decision to set up a meet-and-greet between Murillo and the guy who owns the Colombian sugarcane factory where his family worked).

I’m sure I’m missing a lot. In any case, on the basis of this quick scan of the year’s highlights, the social background of contemporary art looks relatively homogeneous. When it deviates from the middle-class norm, it is at least as likely that to do so in the direction of extreme wealth as in the direction of a poor or working-class upbringing. As with so much else having to do with the art economy, normal reality is inverted.

I stand by my affection for Rose’s Everything and More. Go see it. Yet reviewing Blake Gopnik’s New York Times profile of Rose, a detail does leap out:

[A]rt for art’s sake simply didn’t mesh with an upbringing, on a farm in upstate New York, where dinner-table talk was about weighty issues, hashed out between a mother in humanitarian aid and an urban planner father. (She tidily leaves out one detail: His “planning” comes in the context of a vast real estate empire. Jonathan F. P. Rose, who develops sustainable housing, is the scion of the same Rose clan whose name is on Manhattan’s Rose Center for Earth and Space and the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Rose Cinemas.)

To be fair to Rose, this is the way that class is dealt with in general: it is tidily passed over. No artist wants to be have her work dismissed as the product of unearned advantage. (“It is very bad for Dash to be associated with the De Menils,” Snow’s grandmother and patron Christophe De Menil once bitterly chastised a reporter. “Because people feel, oh, he is leaning on it or that it is like putting a title to your name, like using baron.”)

But a lot depends for visual art, both in terms of public good will and its own self-perception, on its being thought of as a field with broad social significance rather than as a quirky subculture for the well-to-do, like dressage. And the conspiracy of silence around this subject forestalls thinking constructively about how visual art might actually become the more broadly relevant thing its fans believe it to be.

Seattle author David Shields, winner of the 2015 James W. Ray Distinguished Artist Award

Image: Courtesy Artist Trust

To take one example: Jen Graves has a tremendous post in The Stranger asking whether grant-making organizations should do more to make sure that their awards benefit artists who are actually in need.

Evidently, the Seattle-based Artist Trust bestowed its top $50,000 art award, meant to help struggling artists “pay the rent and meet their most basic needs,” to writer David Shields. Fairly or unfairly, this raised eyebrows, because Shields stars in an autobiographical film (directed by James Franco) where he talks openly about a $200,000 income. That may not be enough to put him in Washington’s One Percent, but it does indicate that he has his “most basic needs” pretty well covered. (He is also, incidentally, collaborating with Franco on a forthcoming book of Lana del Rey fan fiction.)

Cover for Flip-Side: Real and Imaginary Conversations with Lana Del Rey, by James Franco and David Shields (Penguin: March 2016).

Graves presses the Trust on the issue. The award’s inventor insists that “the excellence of the work” be the only consideration. Its director explains that considering financial need is “not something that we’ve ever done before, and I don’t know who has done that.”

At the same time, he also admits that three years ago, the Artist Trust wasn’t tracking the race or gender of grantees either, and that since it started actually paying attention, its awards have become more representative on both fronts (though, given the degree to which both race and gender intersect with questions of economic resources, I’m skeptical that they can be fully representative without the added consideration.) Asking about need, however, would be “invasive into the artist’s lives.”

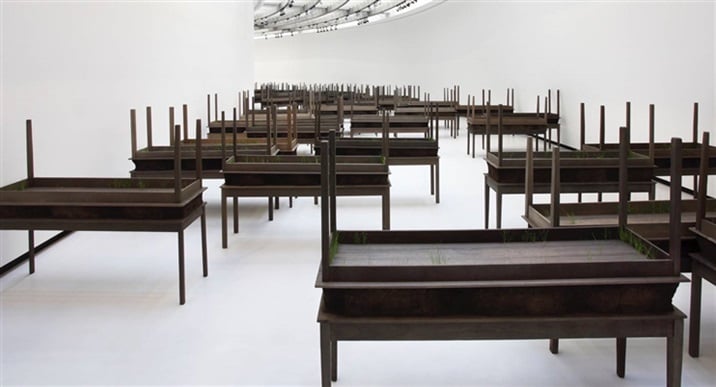

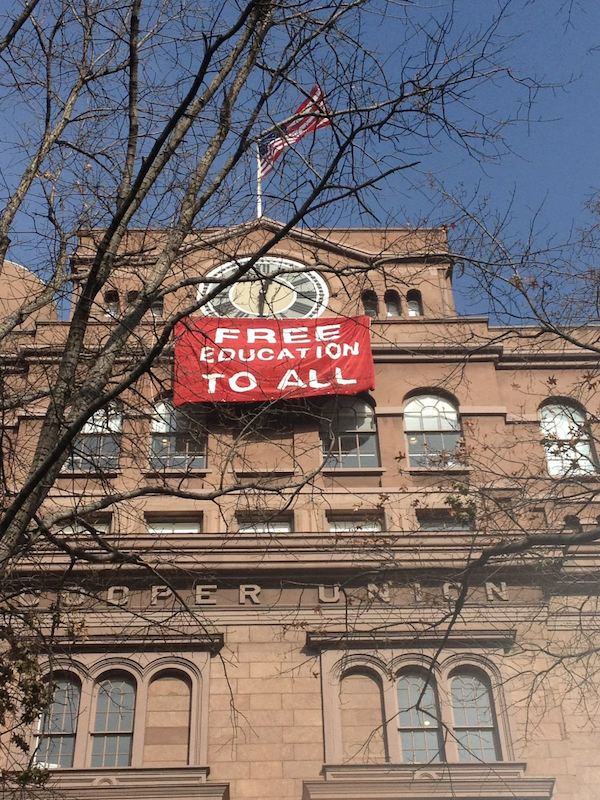

A banner hangs on the front of the Cooper Union during the student occupation of the school.

Image: via Free Cooper Facebook.

Economics remains a blind spot at the heart of the discourse. It is such a blind spot, in fact, that I can’t even really know whether the assertion that “more and more cultural space is being occupied by extremely wealthy cultural producers” is correct. I have only the data of ad hoc counting exercises as a guide.

That British survey takes place in the context of cuts to public funding for culture, and is explicitly framed around the hypothesis that there has been a decline in social mobility in the arts. In the US, there are plenty of local stories, like the ending of free tuition at Cooper Union, that would suggest to me that the odds have gotten longer for those who aren’t born into privilege. (It may be worth noting here that the Rose family plays a bit part in that story: Rose’s grandmother, Sandra Priest Rose, sits on the school’s much-hated board, which made that fateful decision. Her father, Jonathan Rose, happens to have been the developer behind Cooper Union’s flashy, costly new building, which went significantly over budget and has been a financial stone around the school’s neck.)

The truth is, I just don’t know how much longer the odds have become.

We haven’t even turned on the lights, let alone begun to figure out how to get the house in order.