“What if art was violent? What if art hurt? What if it scared the shit out of you?”

So asks journalist Terry McDonell in Burden, a new documentary tracing the career of daredevil artist Chris Burden, as he recounts photographing the artist in the act of pointing a gun at an airplane shortly after takeoff. The film shows the artist’s arc from a performance art provocateur who risked his own safety—and that of others—to the creator of family-friendly, upbeat public sculptures. (His Urban Light, which lives outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) has become an unlikely emblem of that city.)

Produced and directed by Timothy Marrinan and Richard Dewey, the film ably lays out the artist’s lifespan, from a troubled young man who moved like a tornado through the lives of those around him to a humble-seeming elder statesman of contemporary sculpture. Burden draws on interviews with the artist late in his life as well as abundant documentary footage of him as a young artist—from performing his legendary early artworks to television appearances and interviews (one of them with Regis Philbin) to his own home videos.

Abundant time is devoted to his most legendary artworks, complete with original footage and the testimony of the few who saw them unfold live and who still seem stunned. In one early graduate school project, Burden enclosed himself in a tiny locker for five days. “That was the talk of the campus,” says artist Ed Moses says of the piece Burden created at the University of California Irvine. Artist Larry Bell, who was teaching there at the time, recalls that, for him, the piece set a new standard: “I told all the students that whatever they did, it now had to include as much effort as Chris had put into that thing. I thought he was phenomenal, a magician.”

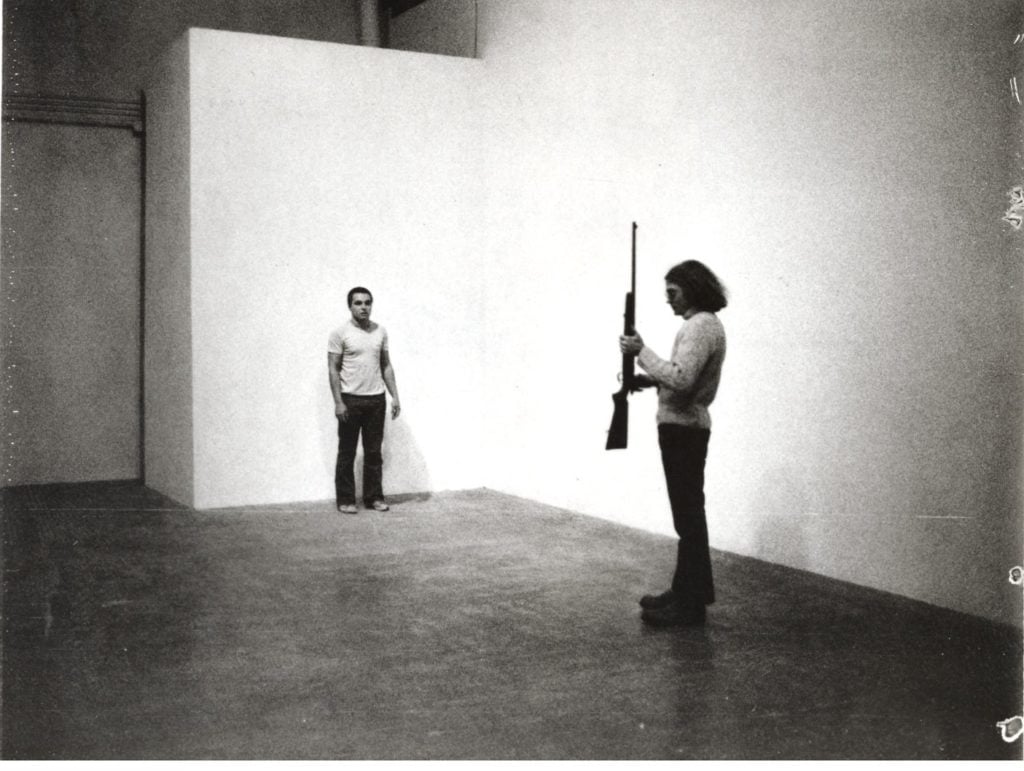

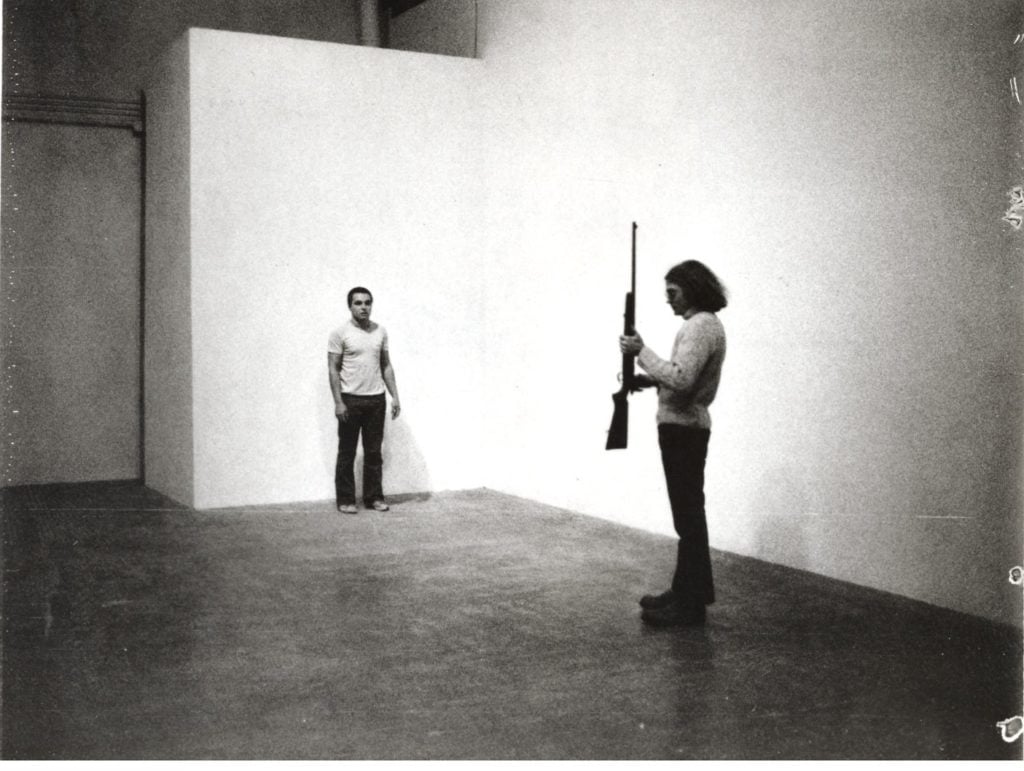

A still from the new documentary Burden (2016), showing the artist performing Shoot (1971). Courtesy Magnolia Pictures. © 2019 Chris Burden / licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In another piece, aptly titled Shoot, an artist friend, Bruce Dunlap, shot Burden in the arm with a .22 rifle. The bullet was only supposed to nick Burden’s arm. “I guess I pulled a little bit to the left,” deadpans Dunlap. Despite the mishap, Burden thought the work held up a mirror to America. “It’s as American as apple pie,” he says, “either being shot or shooting people.”

The filmmakers adopt an alternating timeline, driving home the pain and peril of career-making early performances and then visiting a soft-spoken 2014 version of the artist at his studio in California’s Topanga Canyon, as if to reassure viewers that Burden did indeed survive his hair-raising youthful work.

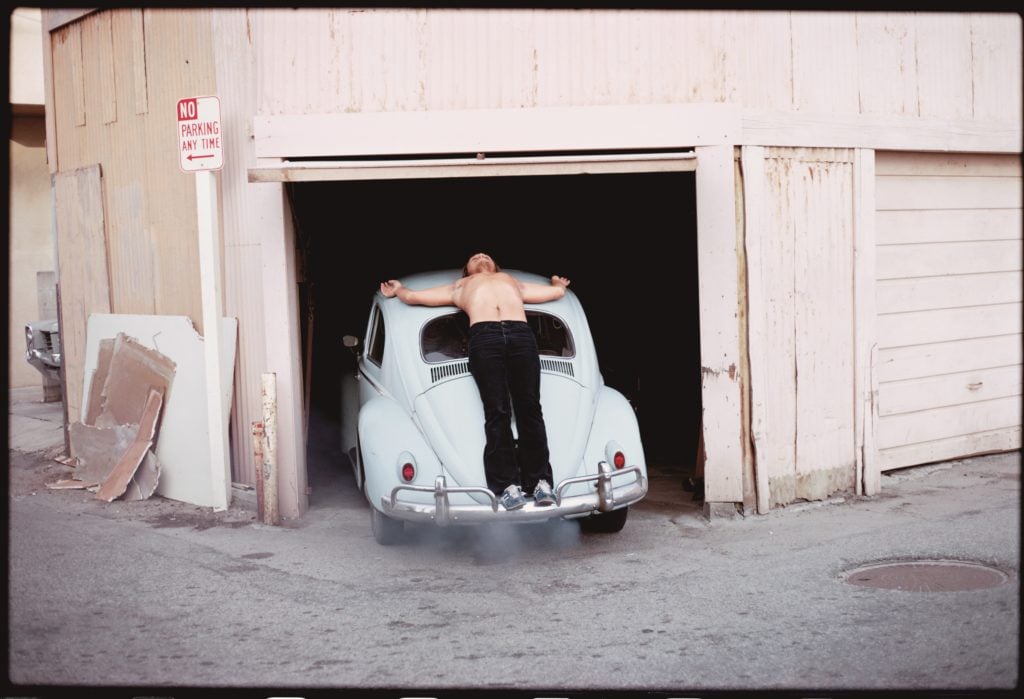

A still from the new documentary Burden (2016). Courtesy Magnolia Pictures. © 2019 Chris Burden / licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In one of the film’s unintentionally funny moments, Burden considers his career and says with a grimace, “I don’t want to do performances now.”

If the film’s approach is a fairly conventional talking-heads presentation, the power of the original footage and the raw content of the early works, which lose none of their edge through repeated exposure, save the film from anything approaching tedium.

The film adopts a rather worshipful attitude to its subject, notwithstanding its clear-eyed look at Burden’s heavy impact, not always pleasant, on those around him. He once performed a piece live on television, for example, in which he confessed to an extramarital affair—without, as she tells us in a voiceover, having told his wife about it first. In another moment, a note from his then-wife Barbara Burden appears onscreen. She was apparently asked to drive nails through his hands for a piece called Trans-Fixed (1972), in which he was crucified on the hood of a Volkswagen. But the terse note reads, “Chris. Cannot do nails. Couldn’t sleep.”

Among those who line up to sing Burden’s praises or to recount their initial shock at his work are a parade of astute observers like New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl, former art dealer and tennis phenom John McEnroe, art collector Stanley Grinstein, critic Roger Ebert, and artists Marina Abramović, Larry Bell, and Robert Irwin, among others.

On the same note, it’s unfortunate that the only critical voice brought into the mix is that of the late English art critic and television personality Brian Sewell, who dismisses performance art by saying it has nothing to do with painting, sculpture, or the other “ancestral forms of art.” Surely, a more incisive commentator, one more comfortable with contemporary art forms, could have been found.

As the artist pivots from daredevil performance art to sculpture, the film inevitably loses some of its suspense. Though it takes a clear-eyed look at the shift in Burden’s output, the film struggles with the same question critic Peter Plagens asks: “He’s the guy who had himself shot. How can you get out from under that?”

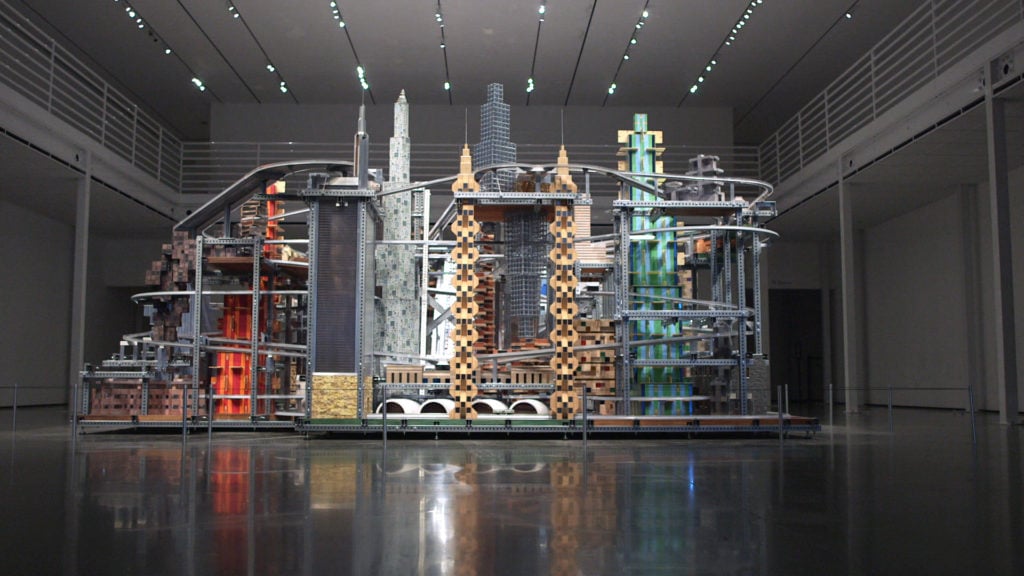

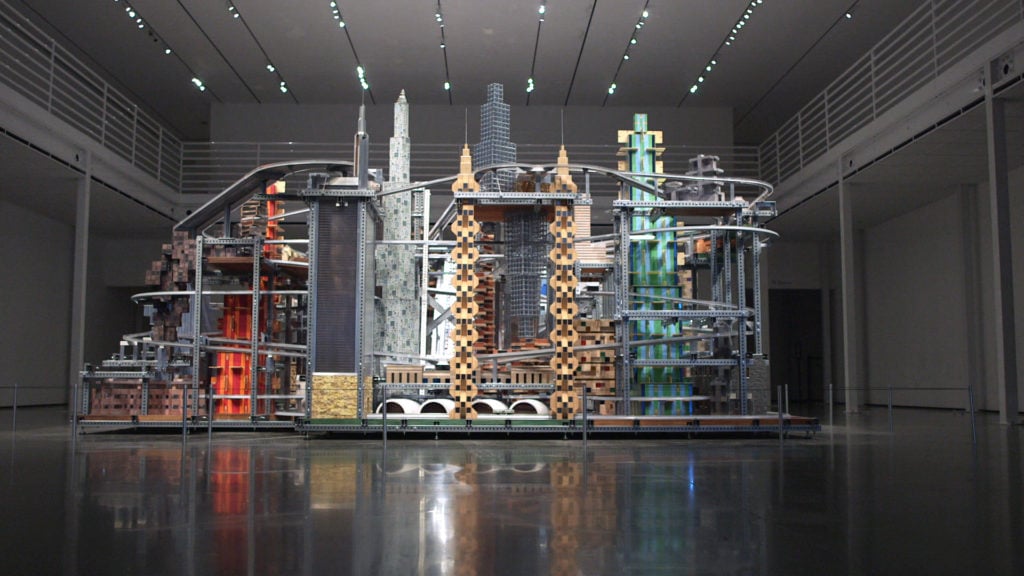

A still from the new documentary Burden (2016), showing Metropolis II (2010). Courtesy Magnolia Pictures. © 2019 Chris Burden / licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Burden found a way, creating sculptures that were as ambitious in scale as his early performances were grueling. But while Beam Drop (1984), in which he plunges I beams from a great height into a pit filled with concrete, echoes the macho quality of the early work (and that of the Abstract Expressionists), something more child-like comes into the picture with works like Metropolis II (2010), in which hundreds of toy cars race along toy highways in a room-sized installation that Burden referred to as “a vision of Los Angeles.”

A still from the new documentary Burden (2016), showing Urban Light (2008). Courtesy Magnolia Pictures. © 2019 Chris Burden / licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Completing Burden’s shift to works that are at once massive but in a certain way humble was Urban Light (2008), in which two hundred salvaged urban street lamps form a sculptural installation-cum-light artwork outside LACMA. If the footage of a man proposing to his girlfriend (and her accepting) is a bit precious, Burden’s humility in speaking about the work is startling for a man whose ego was so clearly imprinted on the early output. Speaking of recent works like Urban Light, he says, “They are not about me as an individual artist…People just enjoy them and they get great pleasure from them and they could care less who the artist is, and in a certain way that’s fine for me because it means that the artwork is bigger than the maker.”

Burden died in 2015 at the age of 69, and if a writer submitted a script with such a touching end, a Hollywood producer would likely send it back. When he died, Burden was working on a kinetic sculpture in the form of a flying, blimp-like sculpture, Ode to Santos Dumont (2015), dedicated to a pioneering aviator. Burden died just a few days before its debut, giving rise to symbolism of the soul taking flight that would be unforgivably trite in a work of fiction. The filmmakers give in to a touch of sentimentality here, with shots of dusk descending on Urban Light and shots of Burden’s studio assistants through the studio windows, seemingly stricken.

But these are quibbles. The filmmakers have woven together an abundance of material to paint a sympathetic portrait of an artist whose notoriety might draw an audience, but whose unpredictability and dedication will keep them in their seats far beyond the most infamous of his performances.

Burden comes to New York’s Metrograph Theater May 5, after which it embarks on a nationwide tour.