Art & Exhibitions

Dominique Levy Gallery Revisits the Experimental Drawing Surge of the 1960s

“Drawing Then” is an exercise in market-inspired retro-mania.

© Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

“Drawing Then” is an exercise in market-inspired retro-mania.

Ben Davis

Installation view of “Drawing Then” at Dominique Lévy. Left to right: Adrian Piper’s “Barbie Drawings,” Mel Bochner’s Superimposed Grids <Blue) (1968), Claes Oldenburg’s Blue Toilet (1965), and Robert Rauschenberg’s Orange Body (1969)

Image: Courtesy Dominique Lévy

If you’re an art history nerd, Dominique Lévy’s ambitious show “Drawing Then” is a fine opportunity to do some serious nerding out.

Arrayed along the walls of the Upper East Side gallery’s two floors is an artful cache of 70 drawings and works on paper. They represent the rock stars of 1960s American art—from Robert Rauschenberg to Cy Twombly, and from Robert Smithson to Eva Hesse.

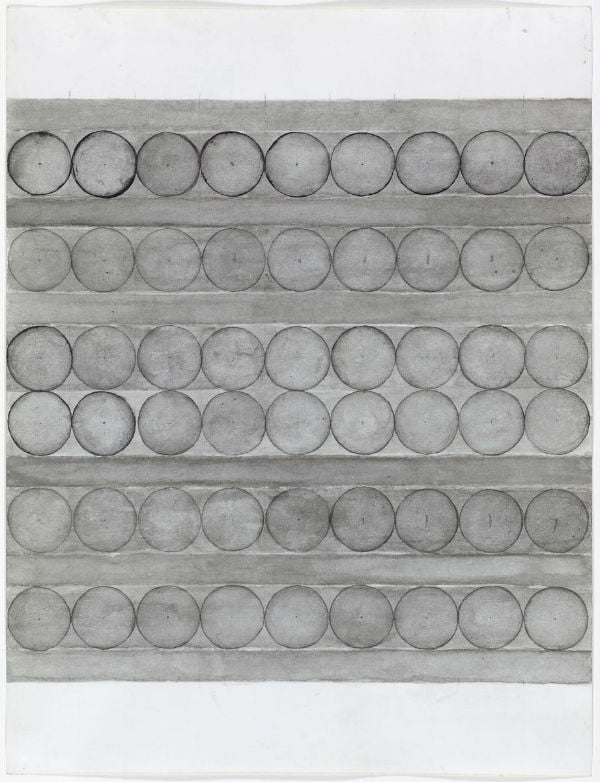

Eva Hesse, No Title (ca. 1965–1966)

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

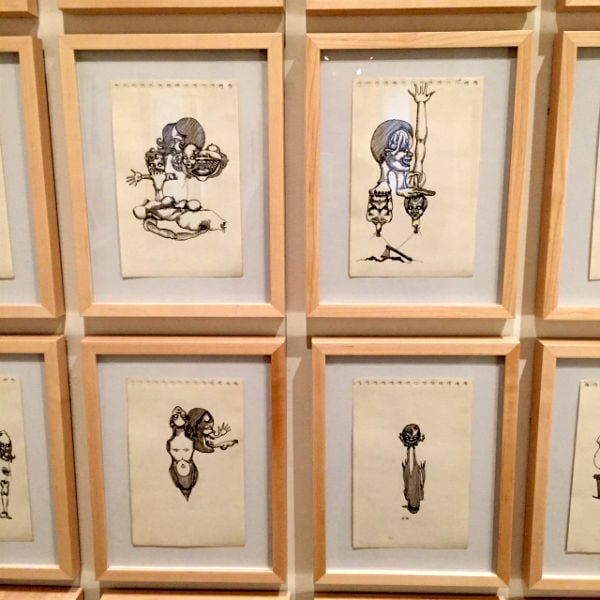

A few of these curator Kate Ganz has secured for the occasion from the collections of MoMA and the Whitney; a bunch more come from private collections, including Jasper Johns’s Wilderness II (1963/70), which arrives from the artist’s own personal collection. There are two wall drawings, Mel Bochner’s Superimposed Grids and Sol LeWitt’s intricate and understated Wall Drawing 20, that haven’t been executed since the late 1960s. A suite of india ink “Barbie Doll Drawings” from 1967, done by a then-18-year old Adrian Piper, brim with surreal discomfort and show a side of the artist that predates her more famous experiments.

Adrian Piper, The Barbie Doll Drawings (1967)

Image: Ben Davis

“Drawing Then” is an exercise in market-inspired retro-mania. It takes its inspiration from “Drawing Now: 1955-1975,” a much-revered MoMA show of 1976, curated by Bernice Rose. That exhibition was more than just a routine drawing survey; it represented a thesis statement about the state of contemporary art, and one that was sufficiently intellectually ennobling to cast a shadow even 40 years on.

In the 1976 catalogue, Rose postulated that “drawing has moved from one context, that of a ‘minor’ support medium, an adjunct to painting and sculpture, to another, that of a major and independent medium with distinctive expressive possibilities altogether its own.” Art in the 60s had become both more brainy, via the mind puzzles of Conceptual Art, and more earthy, via various forms of art that stressed process over product. Thus drawing, with its associations with both the diagram and the sketch, had been summoned to a new centrality.

“Drawing Then” is meant to be in the spirit of that early MoMA show. It does not contain the same works, nor indeed does it even feature the same cast of characters, though plenty of artists make an appearance in both: Chuck Close, Agnes Martin, Bruce Nauman, Dorothea Rockburne, Richard Tuttle, Cy Twombly, and Andy Warhol, among them.

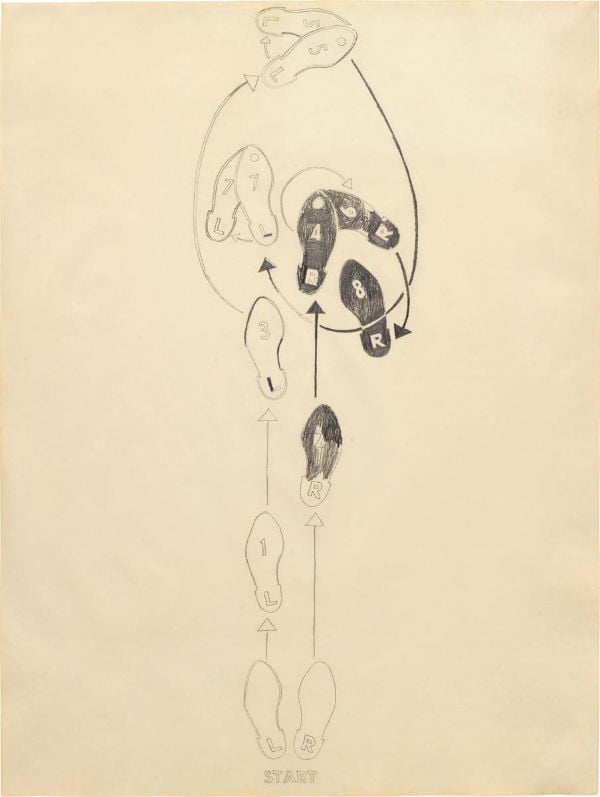

Andy Warhol, Dance Steps, 1962

© 2016 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Digging up the checklist for MoMA’s 1976 show, I find that it’s the substitutions that are interesting. From both shows you would get the overall impression of an adventurous 1960s art scene composed of many novel and eclectic parts. But between the two, the ratio of the ingredients in this pie has changed, so that the overall taste is a bit different.

For instance, the 1976 show had a much larger cadre of artists associated with more hard-line “conceptual” experimentation. Art & Language, Hanne Darboven, Öyvind Fahlström, and Lawrence Weiner were all foregrounded by Rose, as were a few with more difficult-to-classify conceptual-mystical temperaments, like Joseph Beuys, James Lee Byars, John Cage, and Blinky Palermo. None of these find their way to Lévy.

Conversely, quite a few Pop artists who went missing at MoMA appear here: James Rosenquist, Ed Ruscha, Wayne Thiebaud, John Wesley, and Tom Wesselmann. To my eyes, for all its mass-cultural savvy, Pop art tends to put drawing to its very traditional use, as prelude to more resolved final works or as a more intimate, diaristic addendum to the main act.

Wayne Thiebaud, Ice Cream Cone, 1964

© Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Back in the 70s, Rose included plenty of works that would fit into this category as well. But her core thesis was secured via such experimental touchstones as Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning (1953), the infamously cheeky work for which he took a drawing by the Ab Ex pater familias Willem de Kooning and erased it, showing the defaced work as his own, or Piero Manzoni’s Line 1,000 Meters Long (1961), a simple straight line on a long piece of paper, rolled up and displayed in a canister—the potentially limitless energy of draughtsmanship, bottled.

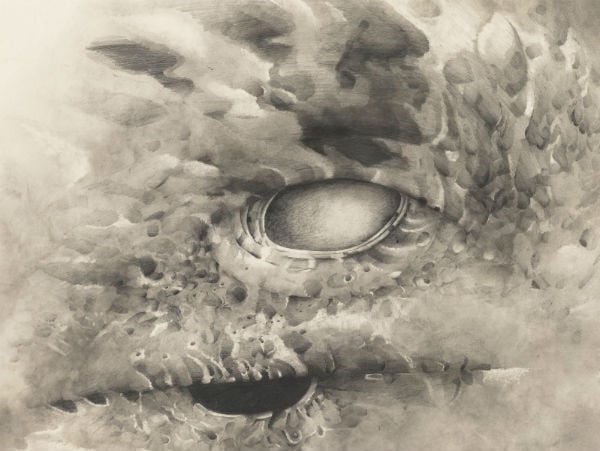

In “Drawing Then,” the works that stand out fit a more classical profile for drawing: Vija Celmins’s large Untitled (Big Sea #2) (1969), a graphite rendering of a tousled ocean surface that is both photographic and verging on abstract pattern at once; or Lee Bontecou’s Untitled (1964), a vortex conjured on paper using graphite and soot, evoking the form of her more famous reliefs, but taking off into wild, atmospheric other worlds.

Lee Bontecou, Untitled (1964)

© 2015 Lee Bontecou

In the end, no matter how “museum-quality” it is, a gallery show has different pressures on it than a museum show, so it’s probably unfair to give its thesis the same kind of scrutiny. Still, the shift in emphasis here is worth remarking for more than just idle compare-and-contrast reasons. Fifteen years ago, Laura Hoptman curated an exhibition at MoMA, called “Drawing Now: Eight Propositions,” which was an attempt to update Bernice Rose’s project for a new era.

Hoptman’s thesis was that artists in the 1990s had retreated from (or advanced beyond, depending on your taste) the position emblematized by the 1976 show, that “drawing is a verb.” Her catalogue essay was titled “Drawing Is a Noun.” The contemporary zeitgeist, she argued, reemphasized drawing as product again. You could say, perhaps, that the shifting cast of Ganz’s “Drawing Then” reflects that same reemphasis in taste, projected back into art history.

The point is: Go see “Drawing Then.” When you do, you can think about it not just as a sampler of a halcyon past, but also as a more subtle exercise in discerning how that past itself is a work in process.

“Drawing Then: Innovation and Influence in American Drawings of the Sixties” is on view at Dominique Lévy through March 19, 2016.