Art & Exhibitions

A Once-in-a-Lifetime Donatello Show Argues That Sculpture, Not Painting, Was the Ultimate Renaissance Art Form

The artist hasn't had a major show in 40 years.

The artist hasn't had a major show in 40 years.

Sarah Cascone

For the first time in 40 years, Italian Renaissance master Donatello (ca. 1386–1466) has a major solo show—and the curator, Francesco Caglioti, hopes the blockbuster exhibition will help elevate the master sculptor to the level of fame enjoyed by Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo.

The reason Donatello has been eclipsed in the public eye by his countrymen?

“It’s simply due to the fact that he was a sculptor and not a painter,” Caglioti, a medieval art history professor at the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, told Artnet News. “Donatello was a pioneer of perspective, and his work anticipated photography and cinema. He is really very modern. Donatello is the best sculptor, perhaps, who ever existed.”

The exhibition’s two venues, the Bargello National Museum and the Palazzo Strozzi, both in Florence, approached Caglioti about curating the show some years ago, but he’s been researching the artist for around 30 years, and believes Donatello’s contributions to the art-historical canon have been wrongfully overshadowed by achievements in painting.

Donatello, Crucifix 1408). Collection of the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence, property of the Fondo Edifici di Culto, Ministry of the Interior. Photo by George Tatge.

“The Renaissance was the triumph of sculpture,” Caglioti said. “And Donatello was a father of the Renaissance.”

The artists of the period were inspired largely by marble statues carved by the ancient Greeks and Romans, not paintings, of which few survived.

“We have to change our perspective on art history,” Caglioti said. “The Renaissance is a sculptural period par excellence.”

“Donatello: The Renaissance” on view at the Bargello National Museum in Florence. Photo by Ela Bialkowska/OKNO studio.

By bringing together an unprecedented number of works by the sculptor, “Donatello: The Renaissance” could very well help upset that hierarchy.

The 130 pieces on view in what’s been dubbed a “once-in-a-lifetime” outing pair Donatello’s sculpture with paintings by his contemporaries and artists who came hundreds of years later, illustrating his lasting influence.

Andrea del Castagno, Farinata degli Uberti (ca. 1448–49). Collection of the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture, Florence, courtesy of Ministero della Cultura, Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi.

The show includes pieces from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the Louvre in Paris; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Caglioti was also able to secure loans of Donatello sculptures that had never before traveled, such as works from the baptistry in Siena and the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua, and even the bronze sacristy doors from across town at the Basilica of San Lorenzo.

For the show, many of the works have been carefully conserved by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, a public institute of the Italian Ministry for Cultural Heritage that specializes in art restoration. The delicate task required soft-bristle brushes and porcupine quills, treating the centuries-old works with steamed demineralised water and other gentle cleansers before applying a protective coat of microcrystalline wax.

Donatello, The Feast of Herod (1423–27), seen before and after restoration. Collection of the Baptistery of San Giovanni, Siena, baptismal font. Photo by Bruno Bruchi, courtesy of the Opera della Metropolitana.

“They cleaned the bronzes, discovering the very gold covering that was completely hidden by centuries and centuries of dirt and filth,” Caglioti said. “They are very brilliant, with a golden surface that nobody had seen for centuries—they looked almost black.”

(The cleaned works will be shown alongside sculptures that have yet to undergo conservation, and will head to the Opificio delle Pietre Dure once the exhibition ends.)

One of the statues from the baptismal font at Siena Cathedral being cleaned with a porcupine quill. Photo courtesy of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence.

The show also includes the artist’s pioneering marble sculpture St. George (1415–17), made for Florence’s Orsanmichele church and an early example of perspective in Renaissance art, and his bronze David (ca. 1440), believed by some art historians to be Western art’s first free-standing nude male sculpture since ancient times. (Both are from the Bargello.)

Having the show in Florence means visitors can follow with a trip to the city’s Opera del Duomo Museum, home to an impressive collection of Donatello works.

“If you come to Florence,” Caglioti said, “you will have a very very large vision of Donatello’s oeuvre.”

See more works from the show below.

Donatello, David Victorious (1535–40). Collection of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Photo by Bruno Bruchi, courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura.

Donatello, Virgin and Child (Del Pugliese – Dudley Madonna), ca. 1440. Collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Donatello, Virgin and Child (Piot Madonna), ca. 1440. Collection of the Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo by Stéphane Maréchalle, ©2021 RMN-Grand Palais/Dist. Photo SCALA, Firenze.

Donatello, Attis-Amorino (ca. 1435–40). Collection of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Photo by Bruno Bruchi, courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura.

Masaccio, Saint Paul from the Carmine Polyptych (1426). Collection of the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa. Courtesy of Ministero della Cultura, Direzione regionale Musei della Toscana, Florence.

Donatello, Hope (1427–29). Collection of the Baptistery of San Giovanni, Siena, baptismal font. Photo by Bruno Bruchi, courtesy of the Opera della Metropolitana.

Donatello, Leaves of the Door of the Apostles (ca. 1440–42). Collection of the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Old Sacristy, Opera Medicea Laurenziana, Florence. Photo by Bruno Bruchi.

Donatello, Leaves of the Door of the Martyrs (ca. 1440–42). Collection of the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Old Sacristy, Opera Medicea Laurenziana, Florence. Photo by Bruno Bruchi.

Andrea Mantegna, Virgin and Child (ca. 1490–95), Collection of the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan.

Donatello, Saint John the Baptist of Casa Martelli (ca. 1442). Collection of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Photo by Bruno Bruchi, courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura.

Donatello, Saint George Slaying the Dragon and Freeing the Princess (1415–17). Collection of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Photo by Bruno Bruchi, courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Virgin and Child (Madonna of the Stairs), ca. 1490. Collection of the Casa Buonarroti, Florence. Photo by Antonio Quattrone.

Giovanni Bellini, Dead Christ Tended by Angels (Imago Pietatis), ca. 1465. Collection of the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Museo Correr, Venice.

Donatello, Miracle of the Mule (ca. 1446–49). Collection of the Basilica of Sant’Antonio. Archivio Fotografico Messaggero di sant’Antonio, Padua. Photo by Nicola Bianchi.

Desiderio da Settignano, David Victorious (Martelli David) ca. 1462–64. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Donatello, Virgin and Child (Madonna of the Clouds), ca. 1425-1430. Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

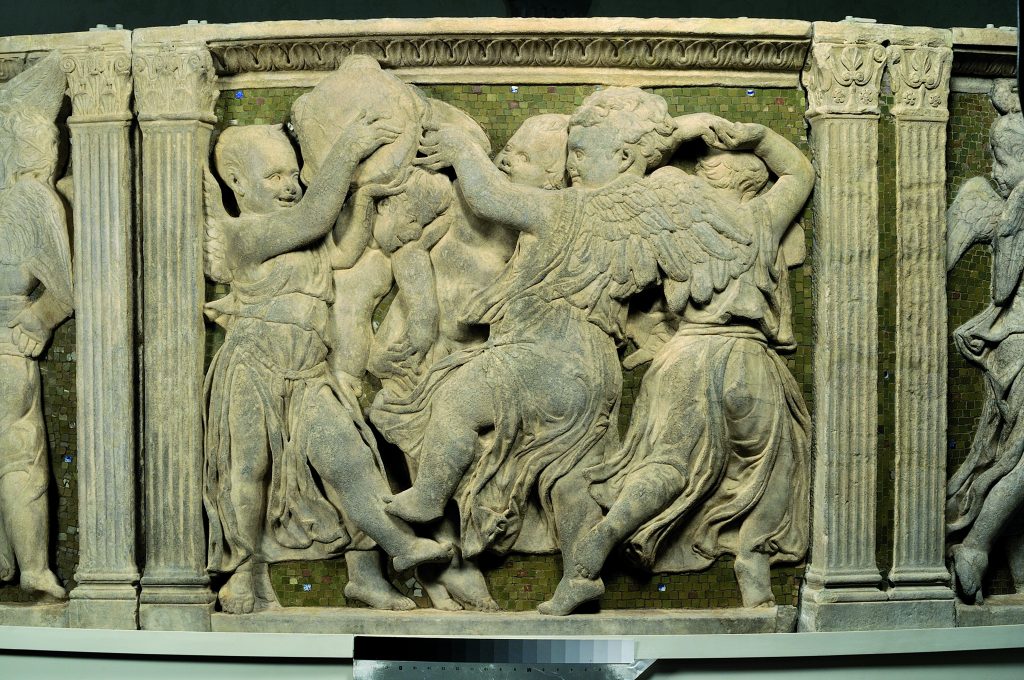

Donatello and Michelozzo, Dance of Spiritelli (1434–38). Collection of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Prato, Diocese of Prato.

Donatello, Reliquary of Saint Rossore (ca. 1422–25). Collection of the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa, courtesy of Ministero della Cultura, Direzione regionale Musei della Toscana, Florence.

Donatello, David Victorious (1408–09). Collection of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Photo by Bruno Bruchi, courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura.

Donatello, Virgin and Child (ca. 1415). Collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst. Photo by Antje Voigt.

Donatello, The Virgin and Child (ca. 1425). Collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

“Donatello: The Renaissance” is on view at the Bargello National Museum, Via del Proconsolo, 4, 50122, Florence, and the Palazzo Strozzi, Piazza degli Strozzi, 50123, Florence, March 19–July 31, 2022. It will travel as “Donatello: Founder of the Renaissance” to the Staatliche Museum Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Stauffenbergstraße 41, 10785 Berlin, Germany, September 2, 2022–January 8, 2023, and the Victoria & Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 2RL, United Kingdom, February 11–June 11, 2023.