People

Doris Salcedo, Whose Haunting Work Bears Witness to Dark Histories, Is the First Winner of a New $1 Million Japanese Art Prize

Salcedo will use the $1 million Nomura Art Award to create a new work.

Salcedo will use the $1 million Nomura Art Award to create a new work.

Taylor Dafoe

Doris Salcedo, the Colombian artist whose haunting, elegiac work bears witness to the history of violence, has been named the inaugural recipient of the $1 million Nomura Art Award, the largest cash prize for art in the world.

Sponsored by Nomura, a Japanese financial services group, the award was founded earlier this year and will be handed out annually to an artist who has “created a body of work of major cultural significance.” The cash comes with only one stipulation: that the winning artist put the funds toward the creation of a new work. (They’re allowed to pocket any leftovers.)

The company announced its first winner at a gala in Shanghai on Thursday evening.

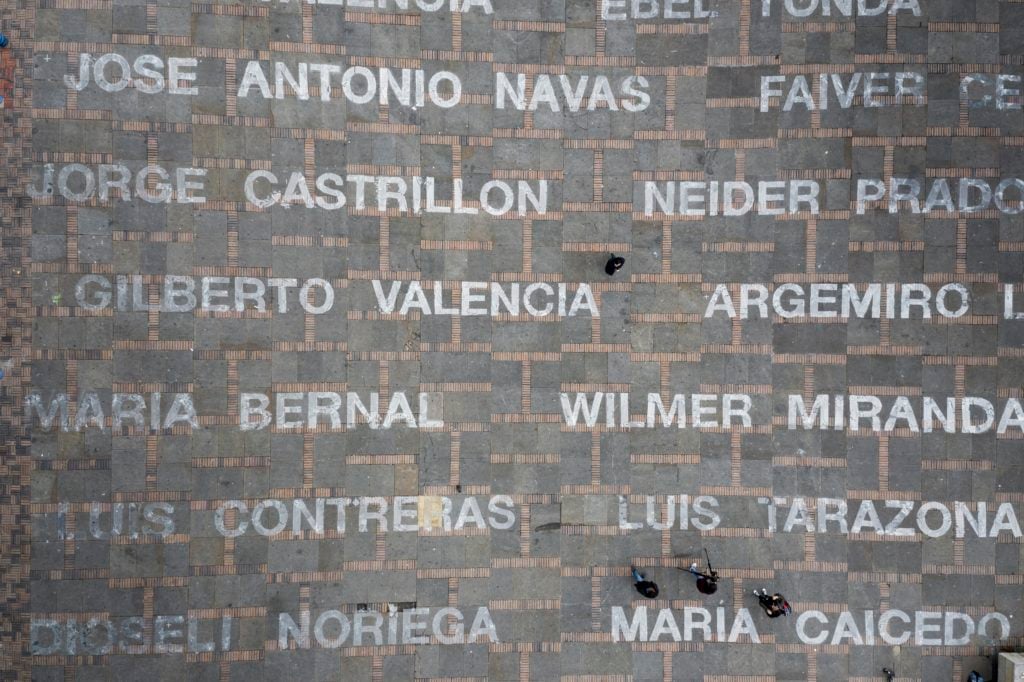

Salcedo will put the funds toward creating a new community-based, performative artwork that, like much of the work she has been making since 1999, transforms domestic, quotidian materials like soil or wooden chairs into monuments that bear witness to unspeakable trauma. But while much of her work has focused on victims of political violence within the Colombian capital of Bogotá, this new work will take her to remote regions of the country, working with communities that are still facing the effects of the country’s five-decade civil war.

“These places that most of us have never heard of, they deserve art,” the 61-year-old Columbian artist tells Artnet News over the phone. “I actually think that’s where art is most needed.”

Doris Salcedo, Quebrantos(2019). Photo: Juan Fernando Castro.

Her new work will tackle unspeakable acts of violence waged by the state.

“In these poor areas, the right-wing paramilitary death squad operated a crematory oven, just like in Auschwitz,” she says. “These ovens were active from 1998 to 2004 and the community has distinct memories of the terrible events that transpired there. I think we need to recover the dignity of the victims and recover this terrain, be able to walk on it, and do something that dignifies the memories of the victims and the life experiences of the survivors. I don’t know exactly the shape it will take; I just know that it will be like an ephemeral, performative piece.”

Salcedo was chosen for the Nomura award by an independent, star-studded jury of curators and museum directors: Doryun Chong, deputy director and chief curator of M+; Kathy Halbreich, head of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation; Yuko Hasegawa, artistic director for the Museum of Contemporary Art; Tokyo; Max Hollein, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Nicholas Serota, Chair of Arts Council England; and Allan Schwartzman, the chairman of Sotheby’s Fine Arts Division and co-founder of Art Agency, Partners. The late curator Okwui Enwezor was also included on the jury before his death in March.

“For more than 30 years, Doris Salcedo has been making sculptures and installations that capture the anguish associated with the loss of loved ones and preserve the memory of traumatic events in the long civil war in Colombia,” Serota said in a statement. “However, her language has an empathy and her materials an everyday character that give her work a universal meaning that speaks to people across the world.”

Doris Salcedo, Untitled (2003), from the 8th Istanbul Biennial. Photo: Sergio Clavijo.

This is the latest in a long line of major awards for Salcedo, who ranks among the most decorated living artists. She was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1995, the €100,000 Velázquez Visual Arts Prize in 2010, a Hiroshima Art Prize in 2014, and was named the inaugural winner of the $100,000 Nasher Prize for sculpture in 2016.

For Salcedo, such prizes are to allowing her to make works that “are completely outside of the art market.”

“About half of my life’s work has not been commercial,” she says. “They’re ephemeral pieces. They’re political, site-specific, time-based. Awards like this give me the freedom to make work like this that is unique and very important for me.”

Such noncommercial work has ranged from filling the streets of Bogotá with a two-mile path of red roses to commemorate the assassination of Colombian journalist Jaime Garzon in 1999, to cutting a 500-foot-long fault line in the floor of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2007.

“Each one of my pieces is completely different,” Salcedo says. “They’re all related to political violence but they’re different. So every time I start a piece I know nothing. I always feel like I’m at the zero point, starting from scratch. Each new work is more difficult than the last.”