Art & Exhibitions

Doris Salcedo’s Uncanny Installations at the Guggenheim Capture Unspeakable Horrors

The show presents room after room of profoundly eerie installations.

The show presents room after room of profoundly eerie installations.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

“Men, quite ordinary men, will compel children to look while their mothers are raped,” Bertrand Russell once wrote. “In pursuit of political aims men will submit their opponents to long years of unspeakable anguish.”

Few writers are as unflinching as Russell in their frank appraisal of human cruelty; fewer visual artists still manage to capture equivalent horrors in their artwork. Yet this is very much the case with the Colombian sculptor Doris Salcedo—whose retrospective, on view through October 12, has taken over the Guggenheim‘s four tower level galleries off the museum’s rotunda.

An artist who has spent some three decades making abstract objects to memorialize routine acts of political violence, her painstaking sculptures and installations invoke powerful metaphors for specific experiences whose expression remains virtually unmentionable.

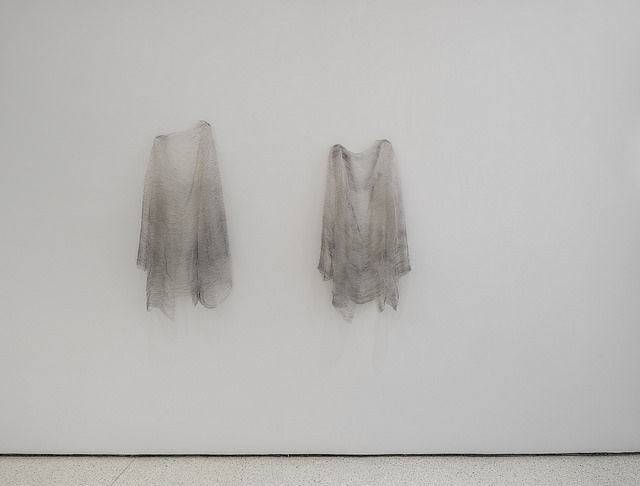

Poetic and political in equal measure, Salcedo‘s sculptures mostly make use of ordinary household objects (chairs, tables, beds, armoires and clothing) which she combines with everyday organic materials (hair, thread, animal fibers, live grass, roses and silk) in order to arrive at unexpected hybrids of the uncanny and the familiar.

Brought together for Salcedo’s first US retrospective—the exhibition debuted at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in February and will travel to the Perez Art Museum in April—her major artworks also liberally mix surrealism with global postminimalism, contemporary art’s Esperanto. Work that often looks like a cross between Dia Beacon-type sculptures and Meret Oppenheim‘s furry teacup, Salcedo’s objects regularly strike notes that are both disturbing and elegiac.

Installation view of “Doris Salcedo” at the Guggenheim.

While the artist’s architectural interventions and large-scale public projects—such as the 548-foot long crack she cut into the floor of the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2007—are relegated to a looped film inside in the museum’s first floor New Media Theater, Salcedo’s eponymous show principally features room after room of profoundly eerie installations.

One of these is Atrabilarios (1992–2004), an installation of forty-three niches housing an equal number of pairs of shoes the artist sewed into the wall using animal guts and surgical thread. Another, Plegaria Muda (2008–10), consists of a large number of inverted coffin-sized tables through which shoots of grass grow from tiny holes carved into the wooden surfaces. Though the first makes use of shoes as distinguishing items capable of identifying the dead in cases of advanced decomposition, both installations effectively honor the victims of Colombia’s mass graves.

Informed by substantial research the artist regularly conducts to give voice to anonymous victims, Salcedo’s interventions invoke actual political violence by abjuring its direct representation in favor of suggestions of its brutal violation.

One example of Salcedo’s symbolic shorthand is Untitled (1989–90/2013), an early work that features eleven stacks of plaster-covered white shirts impaled on steel rebar. An artwork that honors the daily domestic ritual of doing laundry for men who will never return—the installation recalls villagers massacred by paramilitary groups everywhere in the world—it also pays homage to the women and children left behind to absorb lasting psychic scars.

Installation view of “Doris Salcedo” at the Guggenheim.

Salcedo’s work, in fact, makes material and universal an especially moving species of psychogeography. Her various clusters of recovered and distressed doors and chairs from the mid-1990s, which she titled La Casa Viuda (“the widowed house” in English), resemble Frankenstein versions of everyday architecture.

No longer barriers to the outside world or entryways into familiar households, these strange sculptures instead manifest the ongoing mutilation of life’s normal functions by global war and violent conflict. Distorted and zombie-like, their unnatural arrangements stand in for the damage and destruction suffered by locales from Medellin to Charleston.

Salcedo’s use of domestic furniture has also inspired additional sculptures that the artist has characteristically left untitled. To make these works the artist has taken wooden tables, chairs, dressers, bed frames and cabinets and filled in their missing spaces with concrete.

Though they share a common aesthetic with Rachel Whiteread‘s casting of ordinary objects, Salcedo’s pieces provide a crucial social and political dimension that is missing from the English artist’s tamer versions of “negative space.” Not merely a feel-good formalist exercise, the Colombian’s work consistently evokes palpable sensations of human loss; that, and the real-life eventuality mafia films dub the cement shoe treatment.

Yet Salcedo also has an astoundingly delicate way with less orthodox materials. For A Flor de Piel (2012) the artist hand-stitched rose-petals to make an enormous blanket that shrouds an entire gallery floor. A tribute to a nurse who was tortured to death, the work is deeply haunting. It’s always a cliché to say that at artwork beggars description, but in Salcedo’s case words often simply don’t add up.

“Doris Salcedo” is on view at the Guggenheim Museum in New York June 26–October 12, 2015.