Art World

Dr. Seuss Dreamed Up a Guide to Art History That Was Never Published—Until Now

Here's the story of "Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum" came to be published 28 years after the author's death.

Here's the story of "Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum" came to be published 28 years after the author's death.

Taylor Dafoe

Parents, art fans, and horse lovers everywhere all have something to rejoice about: There’s a helpful new museum guide, ready to teach us about art history from ancient Chinese art to the Italian Renaissance to modernism. He is a talking horse.

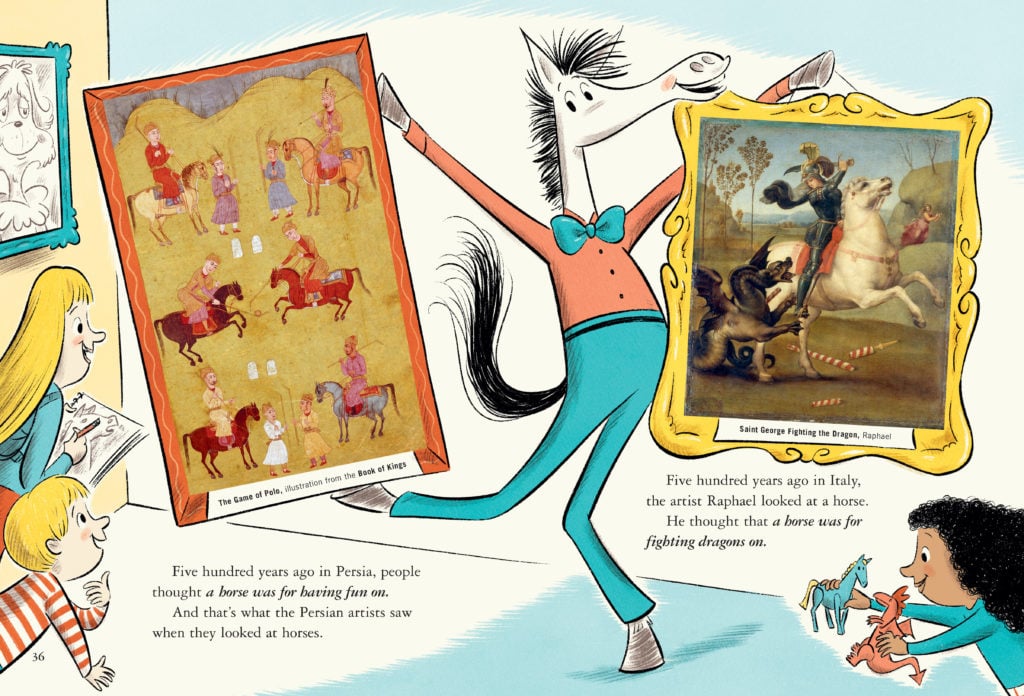

This is Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum, the newest—and likely last—book from the beloved (and long dead) children’s author, whose real name Theodor Seuss Geisel. The highly anticipated book comes out next Tuesday, September 3.

After he died in 1991, Geisel’s manuscripts, sketches, letters, and other professional artifacts were donated to the University of California, San Diego, where they live. However, six years ago, the author’s widow Audrey Geisel came across an overlooked box in their former home in La Jolla, California that housed two long-forgotten, unpublished manuscripts.

Ms. Geisel phoned her husband’s longtime publisher, Beginner Books, and it’s then-president, Cathy Goldsmith. Goldsmith, who had formed a close relationship with the Geisels as a young designer in the late ’80s and early ’90s, was on a plane three days later.

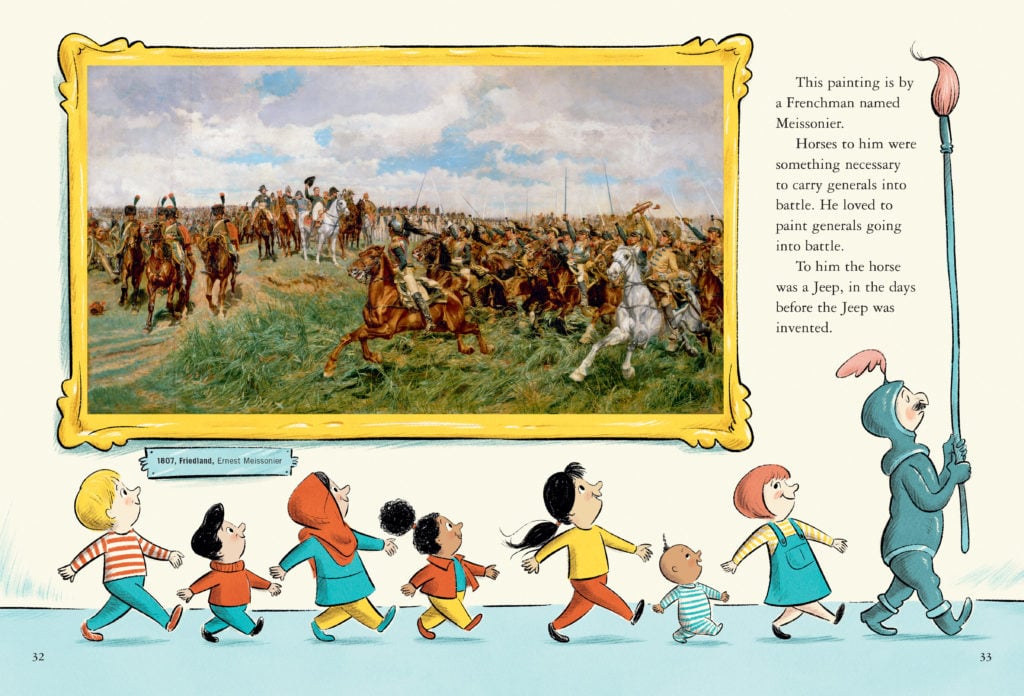

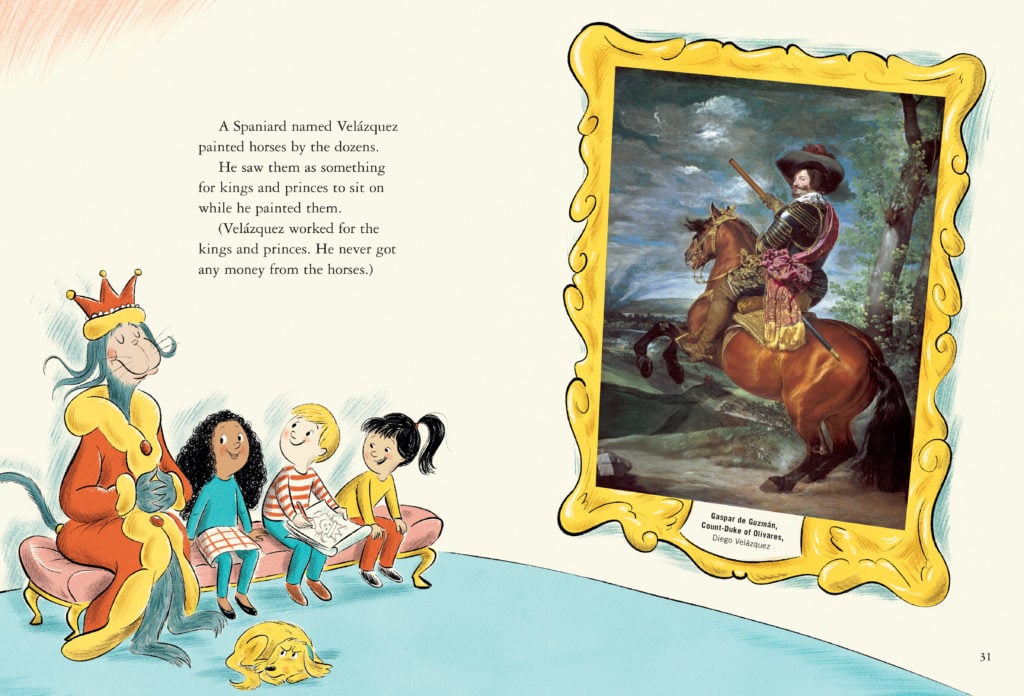

Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum, illustrated by Andrew Joyner, 2019. Courtesy of Beginner Books.

The first of the two manuscripts was a nearly complete version of the story What Pet Should I Get?, which the publisher put out in 2015 and quickly became a #1 New York Times bestseller. The second was a rougher, largely picture-less outline. Adopting the voice of an equine narrator, it charted the evolution of art history through works of art that included horses as subjects—Franz Marc’s Blue Horse I (1911), for instance, or Edvard Munch’s Horse Team (1919).

Though there was no official date attached to the manuscript, Goldsmith believes that it was likely done in the mid-1950s. At that same time, she explains, Geisel had starred in a short-lived children’s TV show called Modern Art on Horseback. Sadly, the footage of the show has been lost.

“I think Ted was probably more interested in art than most people realize,” Goldsmith tells artnet News. “But I really think that, while the book is about art, it’s also about creativity of any kind. He was trying to give people permission to realize that their personal vision is their personal vision and there’s no right or wrong about it.”

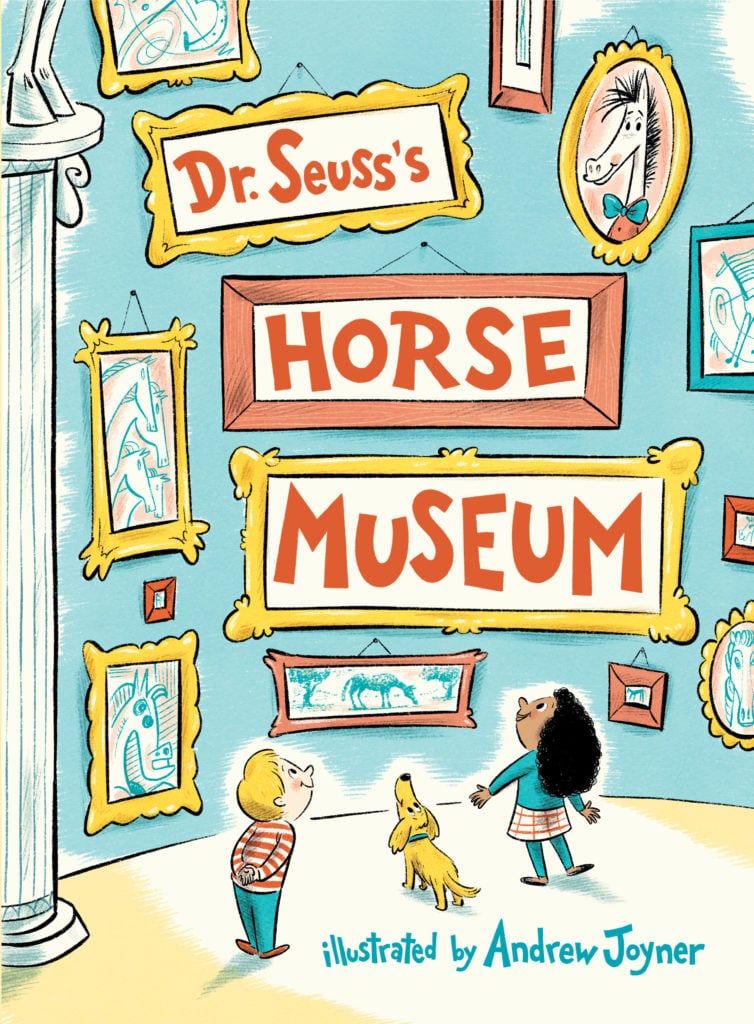

Dr. Seuss Drawing at His Desk. Photo: James L. Amos/Corbis via Getty Images.

Why Geisel didn’t finish the project, we’ll never know (the Seuss-ian illustrations are filled in by Andrew Joyner, who’s also done kids books like The Pink Hat and Romeosaurus and Juliet Rex). The publisher speculates that a non-fiction text on art history might have been a hard sell at the time. Goldsmith also notes that, if indeed it was done in the mid-’50s as she suspects, it would have been right before the publishing of The Cat in the Hat, an instant classic that catapulted him to literary stardom. Suddenly the world of Kandinksy and Calder might not have seemed as interesting as the products of his own imagination, such as the Sneeches or residents of Whoville.

Geisel himself was an accomplished artist, often working on paintings, drawings, and paper-mache sculptures in the evenings after days spent illustrating his books. His work has been shown in numerous gallery shows since his death. In 2017 a museum dedicated to his work opened in his hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts.

For Goldsmith, who is one of the last remaining people in the business to have worked with Geisel directly, the book isn’t necessarily the last chapter of the Seuss story; it’s more like an “addition to his library,” she says. Not lost on her, though, is the fact that the titular horse, a whimsical character guiding readers through an alternate world of imagination and fantasy, can be read as a metaphor for Geisel himself.

“I love the fact that once again it’s Ted or Ted’s character gesturing with their hand and saying, ‘Come with me,’” she says. “I always think of Ted as being, on one hand, a teacher, but on the other hand, a slightly anarchic friend who likes to take you on a little journey to someplace you’ve not been before. I think we all felt the potential in this project from the time we first looked at what we found in the box.”

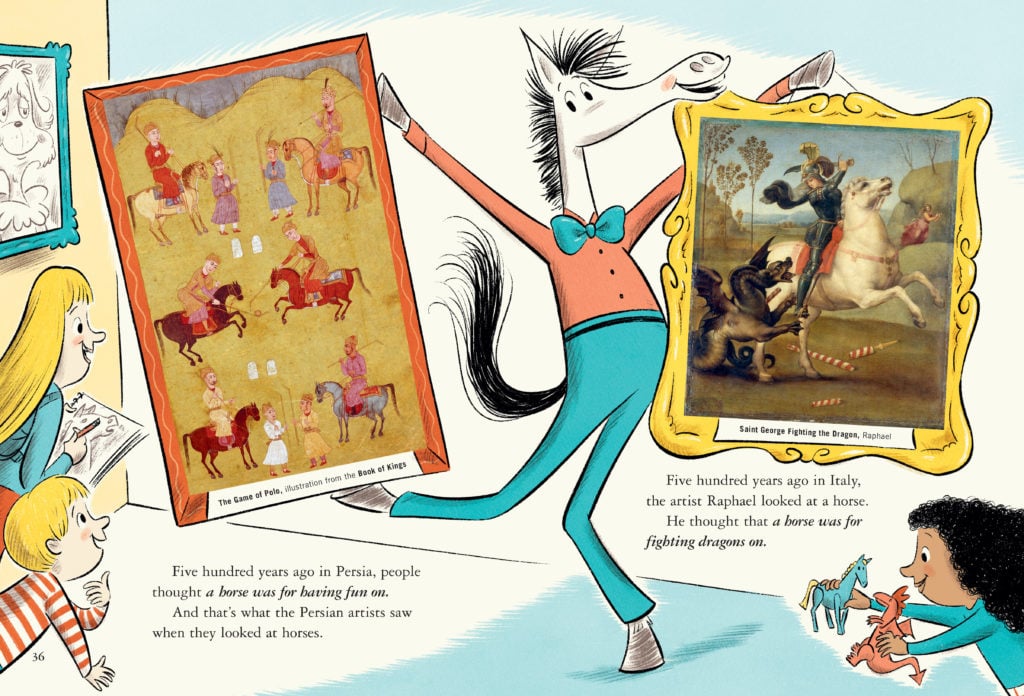

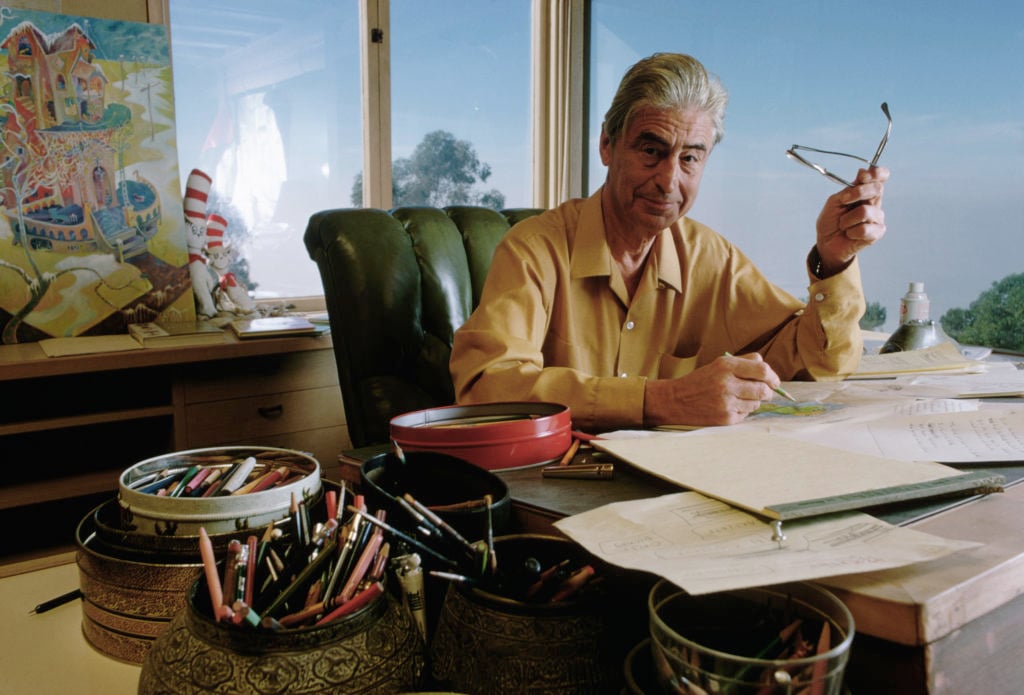

A page from Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum, illustrated by Andrew Joyner. Courtesy of Beginner Books.

A page from Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum, illustrated by Andrew Joyner. Courtesy of Beginner Books. On the wall is Ernest Meissonier’s Friedland (c. 1861–1875). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

A page from Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum, illustrated by Andrew Joyner. Courtesy of Beginner Books. On the wall is featuring Diego Rodriguez Velázquez’s Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares (1635). Image © Museo Nacional del Prado / Art Resource, NY.

Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum comes out Tuesday, September 3, 2019. You can order your copy here.