On View

Why Dutch Golden Age Portraitists Loved Painting Exaggerated Facial Expressions

A new show spotlights how artists Rembrandt and Vermeer made faces come to life with expressive character.

A new show spotlights how artists Rembrandt and Vermeer made faces come to life with expressive character.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

Early Netherlandish painters of the 1400s pioneered portraits as highly detailed, distinctive records of an individual. Two centuries later, artists of the Dutch Golden Age made these faces come alive with an expressive, characterful twist. This genre of smirks, pouts, glowers, and gapes was dubbed the “tronies.”

“Turning Heads,” a survey of “tronies” that features works by world famous Old Master painters like Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, and Johannes Vermeer, recently opened at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin. Some examples of the genre that will be familiar with audiences include Rembrandt’s The Laughing Man (1629–30) and Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat (ca. 1665–67).

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Red Hat (ca. 1665–67). Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

This small jewel painted on panel from Vermeer’s limited oeuvre has a particularly spontaneous air, as though the subject has turned with surprise to see us enter the room. Though no amount of ravishing detail is spared on the rich textures of the woman’s hat and shawl, her face stands out for its strikingly lifelike, everywoman familiarity.

Circle of Rembrandt van Rijn, The Man with the Golden Helmet (ca. 1650). Courtesy of Gemäldegalerie Berlin.

Rather than rely on descriptive documents of a specific sitter that may or may not be saved for posterity, intimate studies of human subjects could be used to capture fleeting interior states with universal resonance. The private contemplation tinged with anguish on this elder man’s face provides an interesting counterpoint to the obviously impressive glimmering gold of his helmet.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Interior with Figures (1628). Courtesy of National Gallery of Ireland.

A rare genre scene attributed to Rembrandt, Interior with Figures is a dimly lit work that contains an ambiguous confrontation between a group, in which narrative depth is provided by the the expressions and gestures exhibited by the central figures. Across the canvas, we can variously read defiance, shock, confusion, and shame.

Michael Sweerts, Head of a Woman (ca. 1654). Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum.

The Brussels-born Flemish painter Michael Sweerts worked in many places, including Persia (now Iran) and Goa, India. In his mid-twenties, he moved to Rome for nearly a decade, joining a movement of fellow Dutch and Flemish genre painters known as the Bamboccianti for their shared interest in everyday scenes of peasant life and people living on the margins of society. Erring from caricature, Head of a Woman is empathetic painting of a humble woman captures some of her vulnerability through its careful depiction of her weathered features, toothless grimace, and teary eyes.

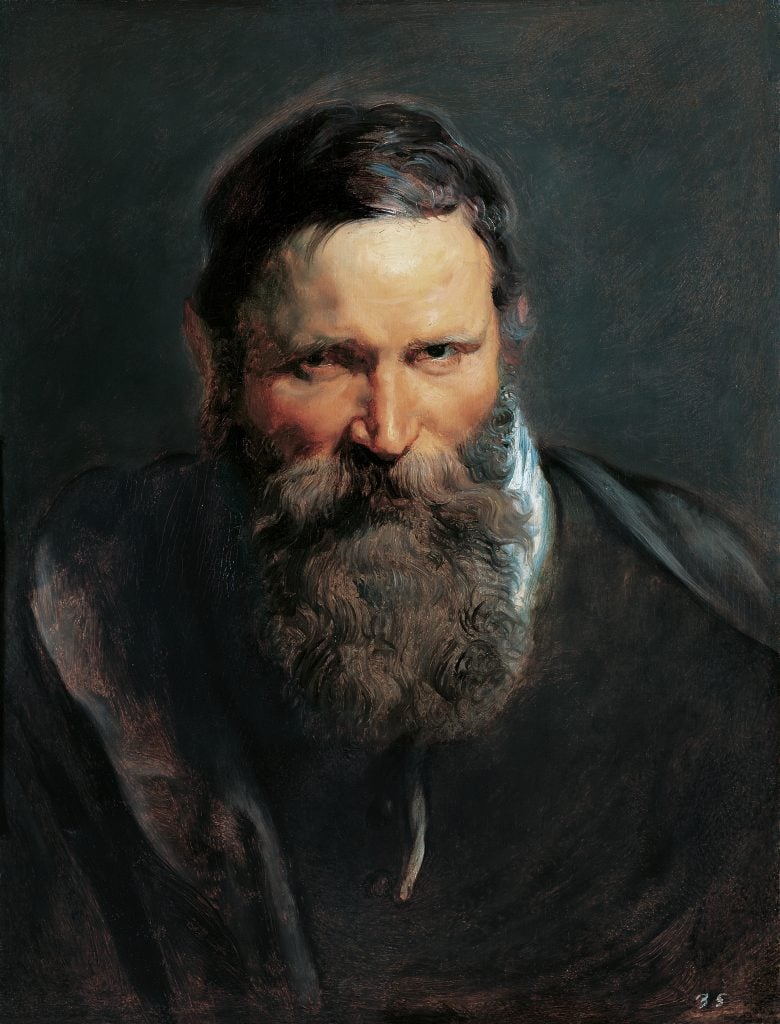

Peter Paul Rubens, Head of a Bearded Man (c. 1612). Photo courtesy of Princely Collections Liechtenstein, Vienna.

With the invention of “tronies,” artists of the Dutch Golden Age and Flemish Baroque era were able to get creative, experimenting with technical skills to bring about fun visual effects. In this way, they also discovered the capacity of painting to materialize otherwise abstract, intangible notions like emotions, age, wisdom, or fragility. Explorations and introspections like these would have a lasting influence on modernism.

Michael Sweerts, Head of a Woman (ca. 1654). Photo courtesy of Leicester Museum & Gallery.

“Turning Heads: Rubens, Rembrandt and Vermeer” is on view at the National Gallery of Ireland until May 26, 2024.