Artists

‘It’s Her World:’ Ebecho Muslimova on Painting Her Uninhibited Alter Ego

The artist has split her new paintings across two shows in São Paolo and Zürich.

The artist has split her new paintings across two shows in São Paolo and Zürich.

Holly Black

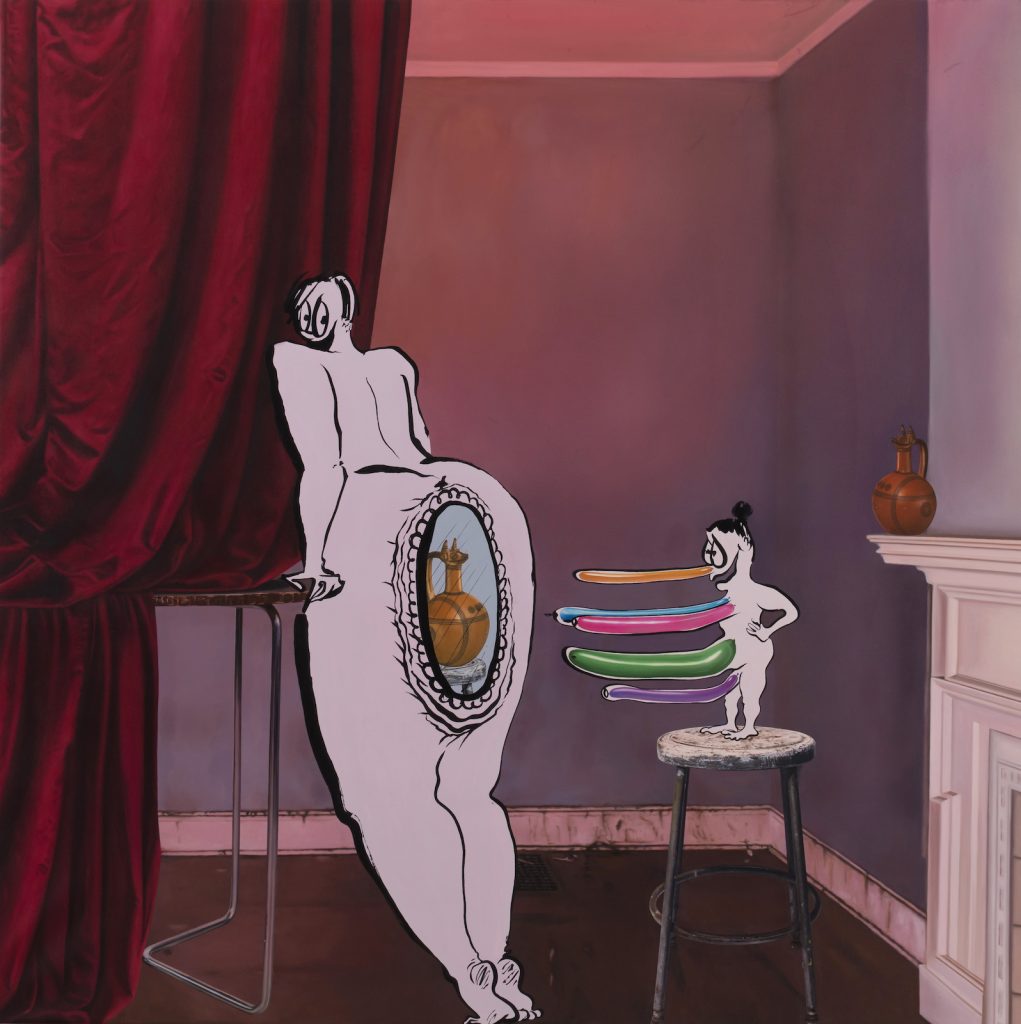

When viewing Ebecho Muslimova’s paintings, it might come as a surprise to hear that she is a bit of a control freak. The artist is known for her uninhibited and decidedly naked alter ego Fatebe, who is articulated in fluid, cartoonish lines.

In every surreal scene this figure inhabits, she explodes any sense of order and replaces it with delightful chaos. Look closer, however, and it is clear that Muslimova has articulated and balanced every element with razor-like precision.

Ebecho Muslimova, Fatebe Clown Boudoir (2024). Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood © the artist.

While this persona began as an exercise in escapism while studying at New York’s Cooper Union, it has become central to Muslimova’s practice. “She is my shield,” the artist explained, “I was very intimidated by artmaking, particularly painting, but now everything I paint is for her. It’s her world.”

When we speak over the phone, the artist is in the middle of installing her new show at Mendes Wood in São Paulo. She has taken the time to clamber off the scaffold, where, with the help of a dedicated team, she is painting murals that appear to extend from her canvases. Thanks to meticulous planning, everything is on schedule. “I am so anal, I definitely have a control problem. I always know exactly where everything is going to be,” she said. “My true nightmare is having to stand in front of a blank wall!”

Installation view of “Rumors” Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood.

For this project, Muslimova has taken her fastidious organization to a new level. The Mendes Wood show opens in parallel with another at Bernheim in Zürich; the two are titled “Rumors” and “Whispers” respectively. Each painting has a partner piece in the other gallery, operating as pairs of “sisters,” as the artist likes to call them.

The inspiration came from the game of telephone, in which people whisper a phrase from one person to another in succession, resulting in strange and often amusing misunderstandings. In her version, the paintings work in dialogue with each other, but are not necessarily speaking the exact same language.

Ebecho Muslimova, Fatebe Dream Bar (2024). Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood © the artist.

“I had this romantic idea of a long-distance relationship,” Muslimova explained, “and the game of telephone has different names wherever you go. In Brazil it’s called ‘rumours’ and others refer to it as ‘Chinese whispers’ or ‘Russian scandals’. In fact, it came about during a time of global Cold War anxieties.”

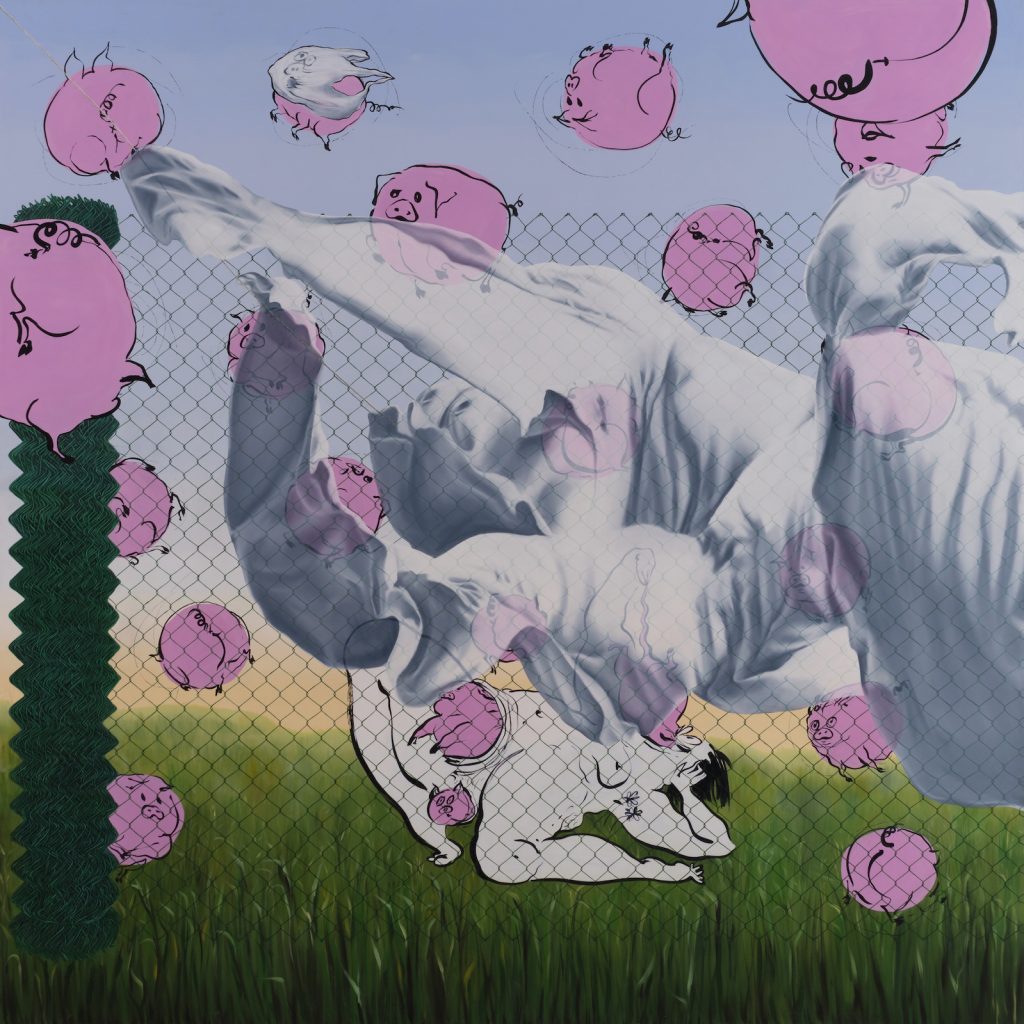

Muslimova upends this context of misinformation and error—something that feels ever more pertinent in the current climate—by embracing the playful and childish elements of the game. “Regurgitating real-world anxieties into forms of play is really cathartic for me,” she added.

Ebecho Muslimova, Fatebe Harvest Day (2024). Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood © the artist.

The artist painted her canvases between her studios in New York and Mexico City, bringing the pairs to life before eventually having to split them up. “It’s a real pain in the ass,” she laughed. “They have to work separately and as a whole, even though they came from the same witch’s caldron.”

Ebecho Muslimova, Fatebe Farm to Table (2024). Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood © the artist.

In some cases, this involves a scenic split in which both paintings operate as a half of a very evident whole. In Fatebe Harvest and Fatebe Farm to Table (both 2024), one figure upends an enormous dining table, which impales another figure on the succeeding canvas. Both works feature an eclectic mix of root vegetables, reptiles and rodents, which Muslimova ascribes to a sense of natural, cyclical decay.

In other instances, the compositional link is less immediate. In Worm to Worm (2024), for example, a contorted green nude appears shocked at a red canvas depicting an anus. The same palette is carried over in Fatebe Rattan Lunch Worm Room (2024), where three individuals crowd around a table. That is not the only connection, though. The art world context is lurking in the shadows.

Enecho Muslimova, Fatebe Worm to Worm (2024). Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood © the artist.

Worm to Worm features a marquee and the New York skyline in reference to the Hamptons Fine Art Fair, while its partner painting includes three characters which have appeared in other works, situated in a room that directly references Kunsthall Stavanger in Norway, where Muslimova will be showing next year.

Through this constant self-referencing, the artist builds a picture of missed connections and the memory schisms that can occur when one is constantly traveling, yet often connecting with the same subjects and people.

Ebecho Muslimova, Fatebe Rattan Lunch Worm Room (2024). Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood © the artist.

These slippages encapsulate the very contemporary feeling of FOMO (fear of missing out), something the artist was keen to explore. In orphaning the pairs, she has produced a sense of longing, not only within the context of the works themselves, but the people coming to see them. With such a vast transatlantic distance between them, only a select few viewers—if any—will see both shows.

This sense of dislocation and distance is something that the artist has experienced in her own life. She recalls emigrating to the U.S. from Russia as a child, following an unexpected separation from her mother of several years. The many fantastical worlds of Disney were at odds with the single, strangely overdubbed video Muslimova had previously had access to. “I think it was Duck Tales,” she recalled. “All the voices were done by one gruff old man, but I loved it because there was this sense that the cartoon came from the place where my mother was.”

Ebecho Muslimova, Fatebe Fenced Pigs (2024). Courtesy of Bernheim and Mendes Wood © the artist.

Once she came to America, she became enthralled by the studio’s famed animations, and the aesthetic has continued to influence her. “I completely fell in love with Disney,” she said. “The seductive line really meant something to me. In combining the same stylistic, fluid lines with meticulous, hyperreal elements, the artist effectively blurs the line between realms of the imaginary and realistic.

“You can see the Roger Rabbit effect on Fatebe,” the artist explained. “She’s placed in an expanding world, where there are very different ideas of what is real. But no matter what, she’s always herself.”

“Rumors” runs through August 8 at Mendes Wood, Rua Barra Funda 216 01152 – 000, São Paulo, Brazil; “Whispers” runs June 7 through July 26 at Bernheim, Rämistrasse 31, 8001 Zürich, Switzerland.