People

The Prime Minister of Albania, Edi Rama, Is Also a Professional Artist. Here’s How He Is Balancing Those Roles During the Coronavirus Pandemic

The nation head talks art and politics from under lockdown.

The nation head talks art and politics from under lockdown.

Kate Brown

The first and only time I saw Edi Rama in person was at an after party for an art opening in Berlin. A hush trailed him around. Exceptionally tall and dressed in gleaming white sneakers, he was flanked by large bodyguards in dark suits.

As he headed in the direction of the dance floor, a gallery assistant leaned in and asked if I had seen the prime minister of Albania’s latest works, on view at the now-defunct Art Berlin fair.

Rama is a dazzling novelty for both the art industry and the world of politics. As both a well-regarded artist and a high-profile politician, Rama cuts an unusual shape in both places of work. His stately office doubles as his art studio, and is decorated in his own signature wallpaper. A rainbow array of felt-tipped markers sit on his tabletop.

On the other hand, Rama might be one of the only artists on the planet who has (and needs) security guards. From a recent meeting with German chancellor Angela Merkel came the usual handshake photos, and then a few shots showing Rama handing her his newest exhibition catalogue, which she flips through with a smile. The 55-year-old does not flinch at how unusual it all really is—and he would actually rather not be asked about it.

Britain’s former Prime Minister Theresa May, Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel and Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama in 2018. Photo: Leon Neal/Getty Images.

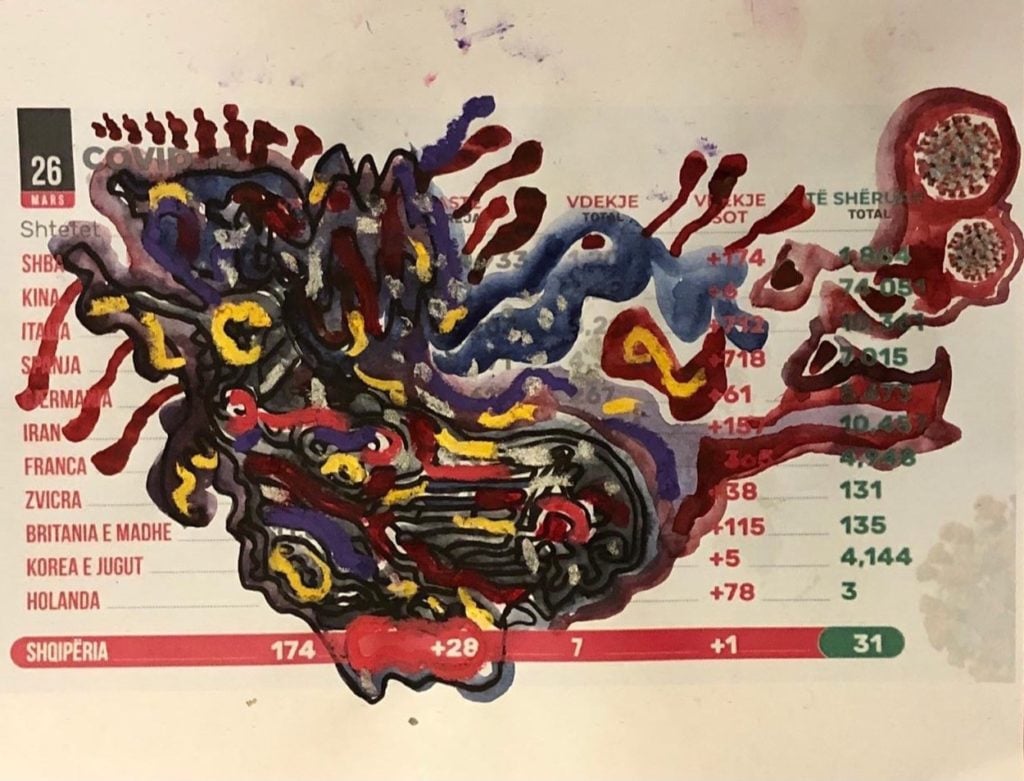

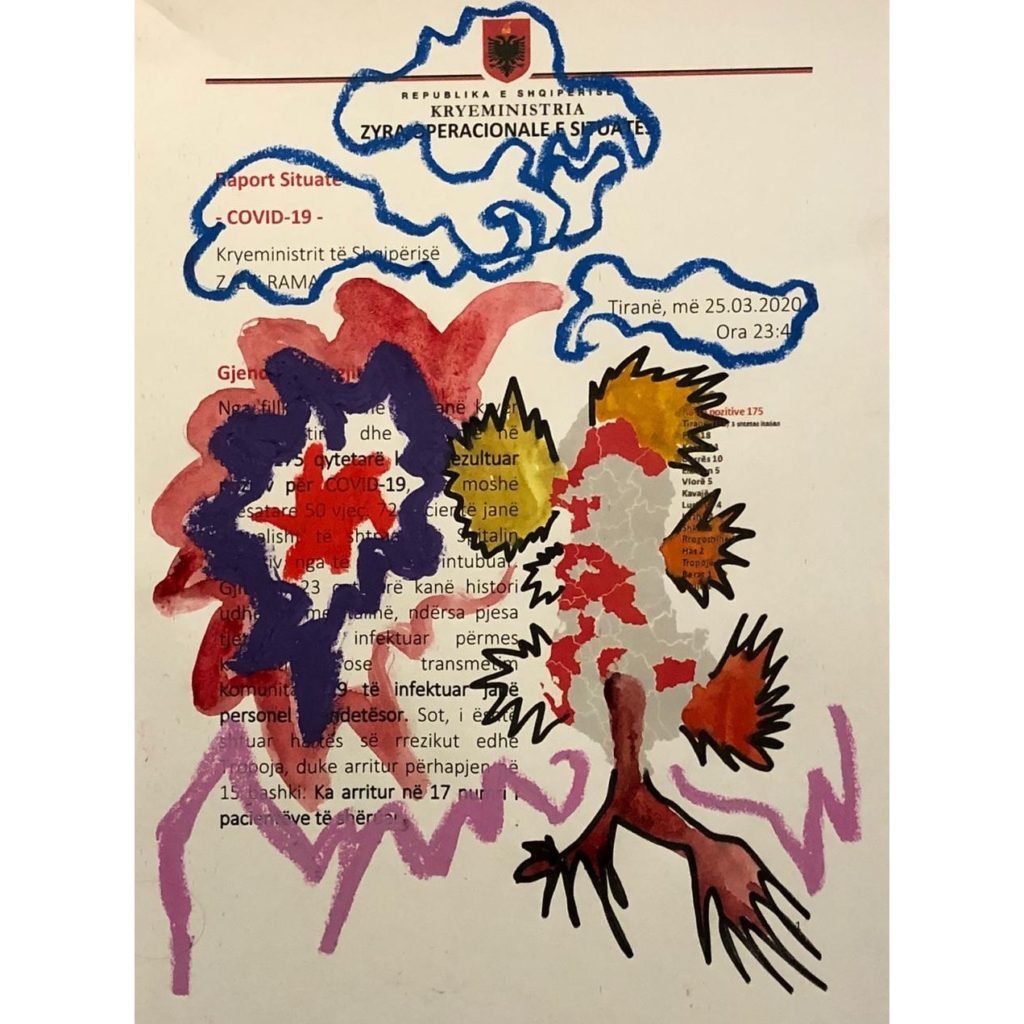

Rama is not exactly a political artist, but his works often occur as drawn-over political documents—meditative tangles of color that seem to grow organically over pages of official Albanian memos. Whether as wallpaper, sculpture, or works on paper, his blooming forms (which range in price from €3,500 to €30,000) seem to provide someone in a high-pressure job a space of anarchy and escape. Whether one finds his two professions to be in discord or in harmony does not appear to concern Rama, who seems to be doing what he loves.

But right now, both of his worlds are in crisis. Albania, a poor European nation that has not yet nabbed EU membership, is perennially struggling with corruption allegations. Helmed by Rama since 2013, it was hit months before the coronavirus by an earthquake. Rama lost his daughter-in-law in the disaster. The country of nearly three million has been in a state of emergency since late November, which was extended with the new health crisis as Rama’s government imposed strict curfews that many deemed controversial and tracking measures.

We spoke to Rama, at a virtual distance, about how the artist and prime minister uses art as an outlet for his current anxieties, how the art market might carry on after the pandemic, and what Albania has in store for memorials to those lost to COVID-19.

Edi Rama, WORK, exhibition view at carlier | gebauer (2019). Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin. Photo: Trevor Good

How are you managing the crisis, politically and as an artist, from home? Are you able to go to your office, which I understand is also your studio?

Politically we are doing the best we can and being aware of our weaknesses, we were among the very first in Europe to implement measures to make people stay at home. As an artist, life continues the same, in my office. Together with my good friend Mia Enell, a great Swedish painter living in New York, we made a nice virtual show thanks to [my gallery] carlier gebauer’s instagram initiative #InTouch.

Your most recent series of drawings, shared with the gallery’s visual #InTouch dialogue, appear on top of political documents related to COVID-19. One is particularly ominous, with a semi-figurative creature emerging from a black entanglement of lines. Can you comment what this particular series means to you, in relation to the crisis, and how you developed it?

They were done in a very particular environment with no people around as there normally would be, while following anxiously the daily data and the projections of the possible spreading. The rest was just the same, throwing lines and colors on the pages while continuing to think about the affairs of the day.

Edi Rama, Untitled (2020). Courtesy the artist and carlier | gebauer.

Art can help in times of great change or crisis. It seems that you understood this in your project that remade the facades in Tirana into brightly painted city blocks in 2003. I understand this project was not an artwork but a political action. Have you been thinking about public art differently now as prime minister, especially as you face down the earthquake and now the COVID-19 crisis?

Not really. I remain reluctant in terms of mixing art with politics and vice versa, although I must admit that my artist background greatly defined my way of looking at the space of political action and the need for beauty in public space.

I was sorry to learn that you lost your daughter-in-law in the November earthquake. I also understand that a lot of homes were destroyed. Could an artistically-minded initiative like the Tirana building repaintings of 2003 be a way to revive people’s spirits in the wake of it?

We are working on several sites where people died and rubble has been cleared out for memorials. It’s not easy to deal with such sites, but it’s a necessary process to remember those that lost their lives.

Edi Rama, Untitled (2020). Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer.

With all that is going on, how much time are you able to dedicate to your artistic practice each week these days? Are you still able to go to the ceramic studio?

Unfortunately, the ceramic studio has been locked down and has to wait for better days, which I hope will come soon, although nobody seems to know for sure what the next phase will look like.

The art market has ground to a halt in many ways with fairs and shows postponed and canceled. What could the industry change in order to be more effective when it starts back up again?

I don’t know! It would be very interesting to see if collecting art will remain among the necessary things people will do next, while a lot of what was previously deemed necessary might not be seen as such anymore, at least for a long while. My guess is that, yes, people will not cut out art collecting, although the economics of it is very much suggesting the contrary.

Edi Rama, Untitled (2018). Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer. Photo: Thomas Häntzschel.

The curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist said art is your politics, and politics is your art. Yet I am sure you are fatigued by the constant comparison.

True, I am fatigued. Or, to put it bluntly, I’m embarrassed any time I have to answer this. Maybe Hans-Ulrich Obrist is right, but I don’t see it much in my action. But yes, I very much feel it in my person.

How do the two—art and politics—inform each other for you?

I think they make me who I am and I have difficulty seeing how my day could be without one trying to get some space from the other, all the time.

Last year appeared rocky for you politically, with accusations from opponents and media reports detailing state corruption. Your government postponed the elections due to protests. What is response to dissenters? How has this tense situation progressed?

Yes, there is no middle ground here. It is black or white. Good or bad. Love or hate. We are still in the painful growing-up process, democratically speaking. In many ways we are a teenage society when it comes to politics, which is understandable—until 30 years ago we never had a space where dissent was a normal part of our public life.

What is the current situation with COVID-19 in Albania? You received some criticism for implementing harsh punishments for those who broke safety measures, like offering prison sentences of up to 15 years for breaking curfew.

As I said before, there seems to be not much desire for the middle ground and, more than that, there are a lot of “alternative facts” circulating. It is the democratic right of the press and the people to question the government, but let’s stick to facts: There is no 15-year sentence for breaking curfews. Having been the only European country with no line on pandemics in our penal code we had to put protective measures in place to save people’s lives. The current situation is very encouraging. Imagining the day after? Not so much.